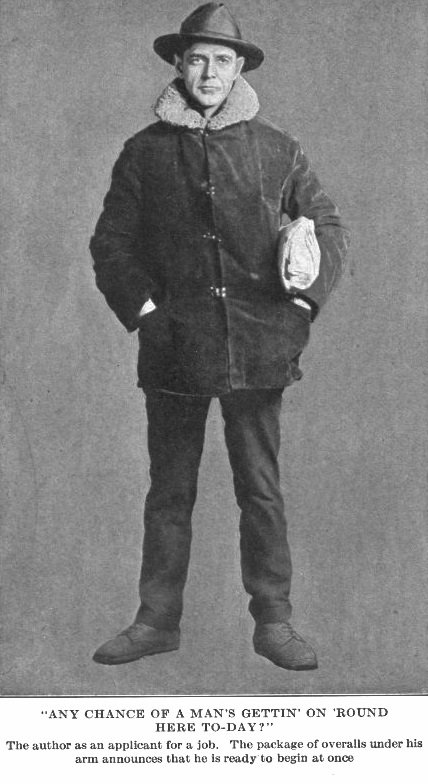

A century ago, Whiting Williams, general staff at a hydraulics firm in Cleveland, OH, took it upon himself to obtain ground truth in the operational reality of large industrial organizations around the USA and Europe. His scheme was to pose as a common laborer and solicit employment like any other itinerant worker. For over three years he went from industry to industry, country to country, working and living with the workforce to get their take on the dysfunctional proceedings. Remarkably, only one supervisor in Germany became suspicious of his gambit.

Williams wrote a series of books from his daily journals and observations. Excerpts from his 1920 book, his fourth, are provided below because he covered everything in our field of endeavor far better than we ever could, with an authenticity that speaks for itself. All of Williams books are available on the massive .pdf thumbdrive library, available to you for the asking.

PREFACE to “What’s on the workers’ minds” Whiting Williams 1920

“WORSE than at any time in history.” That seems the only proper way to describe the present relations between the various persons commonly grouped, in these industrial times, as Labor, Management, Capital, and the Public the investors of brawn, brains, and bullion, and the “bourgeoisie.” For that reason it has seemed, on the whole, desirable to make public in this way records and observations put down at the close of strenuous days and nights, in the belief that the chief causes of the troublesome factors of the situation are as deep as human nature and no deeper.

If, somehow, the experiences described may help to a better understanding of each other’s minds and hearts, the effort will be accounted not in vain. Certainly such a better understanding of the fundamental humanness of all the persons connected with the industrial process, whether in one group or another and most of us are in two or three of those groups at different times is indispensable to both the preservation and the upbuilding of the life of our nation and, perhaps, through it, of the world.

Some effort has been made to restrain the temptation to draw conclusions from the various experiences and testimonies at the time encountered. At the close of their recital I shall make bold to set forth what seem to me proper interpretations, but not without giving them, as now, my full blessing to any and all readers who may find themselves arrived at very different conclusions.

The particular reason for trying to get at the whole matter in this particular way arises from the belief that men’s actions spring rather from their feelings than from their thoughts, and that people cannot be interviewed for their feelings. The interviewer can only listen, and then try to understand because he is not only hearing but experiencing and sympathizing. Since the period described, jobs have become more plentiful. This does not at all weaken my conviction of the fundamental importance to the worker of the daily job as the axle of his entire world. On the contrary, it serves, I believe, only to complicate the whole industrial problem in certain ways, ways which shall receive attention before the book is ended. Whiting Williams, June, 1920.

The next excerpts from the book come after Williams’ presentation of the particular engagements. No other study of the workforce ever approached the scope and depth of his research – to this day. It forms the benchmark of the truth about workforce value systems we have put to use for the last two decades. He did not recognize the foreman as the keystone MitM of the non-dysfunctional organization. He believed top-down ruled to his final breath. All of our mentors did.

SOME OUTSTANDING IMPRESSIONS

And now, what of it? What does it all mean? Certainly the most outstanding impression of all is that I found my companions in the labor gangs so completely human and so surprisingly normal. It makes me smile at myself now as I recall the air of mystery and “differentness” with which my mind had surrounded all these workers back there in the days before I started out to join them. I feel like apologizing to them now for all my wonderings as to whether I could meet the test of their suspicion or the strain of their possible misunderstanding and probable ill will.

My only excuse is that these same wonderings were quite manifestly in the minds of practically all my white-collared friends before I set off. If, perhaps, they were also in the minds of my readers as well, I shall certainly hope that the foregoing pages press this point home, namely, that my hard-working associates my “buddies,” as I now think of them are enormously more like all the other members of our national House of Industry and Life. In every room of that house, also, all seem to find life just about the same nip-and-tuck problem of hopes and fears, satisfactions and disappointments, pleasures and annoyances; in general, pretty much the same mixture properly described as “this pleasing, anxious being.” Wherever found, too, these humans seem just about equally ready and anxious to tell about these hopes and fears, these satisfactions and disappointments, to anyone who will present an ear which is manifestly and sincerely sympathetic.

As I look over the experiences and testimonies reported, I find myself wishing that I could add some of the conversations held with workers and others during the months following my return to well-dressed ways. For these, of course, have contributed to the final impressions without being given to the reader. Perhaps, however, the reader himself has recently heard such testimony as that of the elevator girl and her greeting to me: “Where you been all this time? . . . Yes, this uniform ain’t so bad, but, all the same, it’s why I’m goin’ to quit tomorrow. . . . Well, you see, I’m on what they call the ‘split shift’ a few hours on, then a few hours off, and back again. That makes me change into or out of these clothes four times a day. I can’t see it.”

Next to this fundamental humanness of all of us, wherever we are, the outstanding impression, as I try to marshal the various experiences in single file past the reviewing stand of memory, is certainly this: the most important factor of all in the life of the wage-worker is the job the daily job. For him the day commences with the breathing of the prayer, “Give us this day our daily job.” That is the only way in which the daily bread may be spelled with satisfaction and contentment in a civilization organized for the mass production required for meeting a fast-moving world’s mass needs. It almost makes me shiver with the cold of those February mornings before the great factory gates when I think of the heart-sick dejection, the demoralizing loss of standing as a man, and the paralyzing fear of the bread line which fill the mind and soul of the man who, after days of seeking, has no job and knows not where to find one.

This impression has been greatly strengthened by many recent conversations, both with laborers and executives. Some of these latter say that they still recall more vividly than anything else the hours and days and weeks back there twenty or thirty years ago in the foundry or machine shop, spent in the fear that a lay-off might be required by the company’s business or that discharging somebody might appear to the foreman as the best way for him to ease his mind from some of his vexations. All that I have seen or heard or felt combines to make me believe that it is impossible to see the world as the worker sees it without looking at it through the eyes of the man to whom the need of the daily bread together with the need of the daily hope means the need of the daily job. We are quite likely, also, to miss the real point when we assume so blithely that an overplus of men in New York can easily be remedied by the reported overplus of jobs in, say, Chicago.

Unless the finding of work and the allotment of men to it throughout the country is far better organized than at present, the job in Chicago does precious little good to the jobless man in New York especially if he is unskilled. For, in the nature of the case, the worker who must earn his living by his naked as well as untrained hands is not likely to possess a financial margin sufficient to bridge the distance. The paying or the advancing of his fare has its difficulties and involves considerable risk, especially for the man of family. The saving of fare by the use of the “side-door Pullman” or by ” riding the rods” means the endangering of both his body and his morale by exposing these to the degenerating irregularity of the hobo, or, as he calls himself, “the migratory worker.” One look at the world through the eyes given by this daily need of work, also, makes it immensely easier to understand the worker’s attitude toward the restriction of output “stringing out the job.”

Whether we like it or not, even a short experience will convince anyone that the workman has considerable right to fear, as a practical, day-by-day proposition, that by working too hard or too well he may work himself out of his job that by producing too much he may produce himself out of that indispensable daily bread. Especially to the man hired by the day, the whistle for the end of the turn may announce not so much the beginning of his hours of rest as the foreman’s “Here y’are, Jo! This’ll get your ‘time.’ Won’t need you tomorrow. Work’s all done” and the beginning of that hopeless circuit of the gates in search of further opportunity to earn his “time.” The thought of even a few weeks of that is often reason enough to make the worker feel highly doubtful about the introduction of machinery very hesitant to accept the calm assurance of the economists that he need have no fear because the whole thing is bound to work out in the long run through the increased production and the resultant cheapening of goods. Naturally enough, with his family on his mind, he fears this “long run” may be so long that his self-respect may be destroyed, even though starvation be avoided, before the slack is taken up.

Still further, there seems to be general admission from both workers and executives that unexpectedly large production under an attractive piece-rate has often brought about the rate’s reduction. If that is true, it is not strange if the worker often feels it his duty to himself and his friends not to gamble too much upon the permanency of the arrangement. The understanding of this fundamental importance of the daily job helps also to an understanding of the labor-union. In addition to its more public appearances, on behalf of better wages and hours, the union is likely to be quietly busy helping to find work for its members and then to protect them against unjust firing, to much the same effect as was mentioned so often in support of the representative committee there in the oil refinery.

It is impossible to help wondering if the unions would have grown to anything like their present size if all the managers who find them so serious a problem had felt more keenly how seriously this problem of the daily job touches the life and soul of the worker. In any event it is beyond the slightest doubt that nothing like proper happiness and therefore proper effectiveness is by any means to be expected in the industrial world until more thinking and more organization have been devoted to the increase of security for the country’s working hands and heads in this regard along lines to be suggested in later pages.

The recent months of plenteous jobs are, I am sure, not at all sufficient to affect the value of this fundamental necessity of the job as a keystone to the whole arch of the problem of industrial relations. The result of such months is merely to make the restless situation worse by urging the worker to make good use of the occasion to get acquainted with the advantages and disadvantages of as many different employers as possible during what he is certain will be only a temporary period because an abnormal one. When next week or next month things begin to get back to what he is convinced is their normal tightness, he will know what plant furnishes, all things considered, the best combination of the securities and opportunities he hopes for. If a worker has saved a little ahead, such an “inspection tour” may be as good an investment as spending it in loafing or on some of the ordinary luxuries especially if in the meantime he finds about as much security at the last place as he had originally!

It will surely appear natural enough that the next impression which marches in on my memory is that of tiredness and the connection of this tiredness with its unheavenly twin, temper. Together these two certainly make a vicious circle which deserves the thought of all those desiring either a better industry or a better and safer America. Tiredness seems to cause earlier temper with hardly greater regularity than temper, with its inner friction, causes earlier tiredness. Happiness, either in the plant or the home, appears to be unthinkable in connection with regular workshifts longer than ten hours at the most. Apparently, too, this happiness together with good citizenship is impossible with the long factory turns without much reference to the question of the nature of the work. One of the most violent denunciations of the twelve-hour shift came from a plant policeman: “Why, you guys that work on the floor up there in the open-hearth can go home and go to bed and keep yourselves in good shape. But when we chaps have sat here all day at the gate, we’ve got to take an hour’s exercise or two before turnin’ in or we begin to get fat and slumpy. This twelve hours is the devil all right.”

The bulk of our iron and steel should no longer be made and rolled into the heavier forms on the twelve-hour day and the seven-day week. For the labor gang and for the furnace men it seems beyond question that management must plan somehow to find enough things for a man to do in eight, or at most ten hours, to justify the payment of a satisfactory wage and, at the same time, not too much work for the preservation of the worker’s physical stamina. There can be no question in my mind but that the long turns are uneconomic and wasteful from the view-point of plain dollars and cents.

I shrink with proper shame when I recall the gait we workers took in the moving of those bricks from the furnaces or the “checkers” a gait that required careful observation to determine whether we were moving or not. I remember, however, that even that gait sufficed to bring all the weariness that could be borne either by me, the greenhorn, or by my friends, the old-timers. Certainly all of us grew, almost daily, less and less worthy of the wages we were paid. Certainly, too, few if any foremen prove able to stand the strain to the point of such loyalty to the company as suffices to keep them awake night after night. With the long turns added to the seven day week, it just is not humanly possible.

Whether foreman or worker, such men are paid for energies which they simply are not able to deliver. If it is true, as a member of the War Labor Board reports, that 98 per cent of the disputes they were asked to solve simmered down finally to some petty dispute between a foreman and a man, then I am willing to wager that the majority of this 98 per cent would be found to have occurred when both foreman and worker were just plain tired. Such ill humor, the doctors are assuring us, is the one unfailing sign and symptom of such tiredness. Many foremen, I am sure, are regularly working too long hours: in many cases their responsibilities call for longer turns from them than from the men under them. Indeed, in some cases it would appear that the whole organization, from the president down to the humblest shoveller, is pushing itself too hard in order to meet some emergency which is allowed to stretch itself over the weeks and months until everyone under the plant roof is “on edge” and the stage is set for trouble.

Whether tiredness and temper T. & T. are caused by bad conditions of working or of living, I am convinced that they constitute an explosive which is almost as destructive as the “T. N. T.” of warfare in its effects on the firing Hue of our daily lives and along the larger front of our national safety and development. “A man swears to keep from crying; a woman cries to keep from swearing,” is a saying recently heard that substantiates the “philosophy of profanity” originally set down in explanation of the “detonations” encountered there on my first long-hour job. The connection of these “twins” with the sleep-inducing virtues of the “whiskey-beer” of the same town has been made, I think, sufficiently plain. There can be no doubt, also, that “T. and T.” constitutes a serious menace to the whole country in the way it persuades its possessor to listen sympathetically to the words of the agitator.

Anyone who has carried these twins for days sitting upon his own body and soul wants to counsel every good citizen to beware of the daily headlines which blame all industrial difficulties upon the I. W. W., sower of dissension. It would get us all much farther along if we only would inquire whether tiredness does not supply one reason why these presumably happy and contented persons listen as much as they do to those agitators. It is nearer the whole truth to believe that the agitator earns, or at least works for, the salt of his daily bread by rubbing it into the raw spots and sore spots which our public opinion and our industrial intelligence allow to exist. Of such raw spots and sore spots one great and continuous cause is contributed by these twins. It is largely a needless and a preventable cause because it represents such low-speed work and such high-speed deterioration.

Democracy is not safe in any country where there are hundreds of thousands of tired chronically tired men or, for that matter, women. For that reason, if no other, those workers who want to “make a stake” quickly either for themselves here or their families, or that farm “back in old countree,” and so ask for the long turns, should be refused. The problem of the agitator and his hearing goes over, of course, into the field of ignorance and its opposite in education. Even tired minds would not give the credence they give to the agitator’s false statements “For every dollar you earn your employer earns ten,” or “You earn your wages in two hours of work, what you earn in the other ten or twelve makes his profit” if education, inside the plant or out, put into those minds what it should.

The point is that the installing of proper facts and information are quite impossible when those minds are chronically tired. Indeed, almost all the constructive educational and social agencies set up by a public which wants to be helpful are sure to fail of their mission if they finally impinge upon persons who would be happy to profit from them if only they were not too tired to care. “Want of interest is worse than want of knowledge” if only because without it knowledge is impossible.

Thus the third impression, which marches out like those silent timbers which came forward from the black corridors of the mine, is closely connected with the second: the worker’s ignorance the unskilled, the semiskilled, and, yes, the skilled worker’s ignorance of the plans and purposes, the aims and ideals the character of his employer, the company. This ignorance is not strange. The work of obtaining a mutual understanding between the industrial manager and the great mass of workers who have rushed in during the last few years from all over the known world for taking up their tools in our vast scheme of modern production, is colossal! It takes one’s breath away to contemplate it!

This is especially true of steel, in which America has suddenly forged to the front as the producer of more steel than all the rest of the world combined. This work, too, is one whose accomplishment must necessitate time, time with the help of patience, and, most of all, of sympathy. Meanwhile, it must be understood that the great means for that mutual knowledge which must be added to by mutual sympathy to make mutual understanding, will grow immensely faster by demonstration than by exhortation. The seeing of the thing done the thing which actually happens this constitutes the great primer by which the minds of practically all of us learn the greatest lessons. Statements, arguments, logical exposition, whether by ink or breath: these for virtually all of us are mere footnotes on the page of practical instruction and learning.

One or two, possibly three or four, demonstrations seen unmistakably in the doing of our work and taken into the inner sanctum of our experiences these give us our fixed ideas and attitudes, and so supply the real roots of our education. Perhaps it is well that it is so, otherwise we might believe the false teachers and preachers instead of casting them out when the demonstration given by their lives and works fails to support their words. At any rate, the worker is not to be blamed if he considers his driving foreman or that grouchy gate policeman or that mean-minded paymaster or his pompous clerk quite as fully and as properly a representative of the company’s real purposes as the solicitous employment manager or the friendly nurse or if he sets the manifest waste of materials off against the company’s narrow figuring of its wage rates. For that reason it must be granted that much of the distrust of great corporations is not based so much upon ignorance as, in too many cases, upon bad demonstration.

Nor can the better understanding be obtained merely by the addition of truer demonstrations unless the goodwill is really there to be demonstrated. The solution requires a sincere purpose within the soul of both parties in the relationship and then the conviction that every single contact between the two is sure to be understood as a revelation of that purpose. Especially in the case of the great concerns which now maintain these relationships under the supervision of absentee management, a successful outcome requires an amount of attention which is nothing less than tremendous.

Where the executive in immediate and close-hand charge feels that his sensibilities in the particular understanding of a delicate situation and matters of human relationships are never anything but delicate are practically bound to be rendered worthless after passing through a thousand miles of postal communication, there is set up a hopelessness and a mechanicalness which is sure, in time, to dull those sensibilities. Sooner or later, such dulled and injured sensibilities, on one side or the other, are pretty likely to mean the severed relations which, as recent history proves, are but the vestibule to war.

For all these reasons it is extremely superficial of us to think that we can solve the problem of happy industrial relations or happy American citizenship for the foreign-born worker merely by juggling with the phrase of “Americanization.” The word itself should be dispensed with because it assumes so blithely that what we have already can profit from nothing they can bring and that whatever they bring can be made suitable if they will only let us teach them English and show them the street to the court-house! No Americanism is worth our effort to obtain unless it is an Americanism of good-will, good-will built upon understanding.

And this good-will and understanding of America must be gained, after all, in exactly the same way as the understanding of the company and its purposes by demonstration. It is for us, therefore, to look more to the demonstrations of a likable or unlikable Americanism which are given every time a foreman commands, a judge instructs, a salesman sells, or a newspaper reports, assumes, or exhorts. It is idle to suppose that the teacher of English is going to make his printed pages offset all the force of the demonstrations of all the other contacts which the worker makes from day to day with all of us. It is folly also for us to assume that all our teachings must wait upon his learning of his English.

There are many, many things which should be gotten over, through his own language, to the worker whose years may now be too advanced or whose working hours are much too long to permit the learning of our tongue in time to be of service to us. In the making of these contacts, also, and especially if we have in mind his joining an English class, we should try to reach the worker not so much through his friends and compatriots at the plant, but through the larger group of his friends in his particular settlement or colony. If we cannot by all our demonstrations in all our contacts with that colony and its leader succeed in “selling America” so as to have their combined good-will in the learning of our ways, then perhaps we should take a look at our ways!

Of the seven months’ experiences, these appear to me the outstanding impressions. Beneath them, and tying them together into the whole great organization of modern life and work, are some deeper factors which should be looked at before we talk about the way out. . . . Meanwhile neither our classes nor our contacts will be found to “demonstrate” an Americanism which the foreign-born worker is likely to find attractive unless we can first of all come to a deeper realization of that fundamental humanness which makes him enormously more like us in all the larger reaches of his thoughts and feelings than unlike us.

In order to make it easier to think about the industrial worker, it has long been the fashion of the philosophers to describe him as the “economic man” interested in playing his part in the process of production or distribution, more or less exclusively for the purpose of thereby earning his daily bread, and, with good luck favoring, his daily jam and cake. “All he wants is in the pay envelope” so more practical and experienced observers are apt to voice the same effort to find an all-inclusive rule of modern human action. Such a man, it goes without saying, will have only an incidental interest in the nature, the hours, or other conditions of his work, or the character of his foreman, or his company, so long as he takes out of the plant enough money wherewith to buy in the remaining hours of his day the satisfaction of his real desires as a person among other persons. This explanation of the mainspring of men’s doings is highly popular.

To my great surprise I found it used quite as much by the worker for the explanation of his employer’s behavior and especially his misbehavior, as by the employer for the understanding of the worker’s comings and shortcomings. But something must surely be wrong with a mainspring whose effectiveness is so readily accepted in the case of the “other fellow” and so strenuously denied in our own. At the very least an enormous amount of proof ought to be required in order to substantiate on any universal basis a theory which no one can be found willing to admit for himself or for anyone else except the person he does not intimately know.

Of course the dilemma may be partly avoided by making the all but universal assumption that putting men into the group called Labor or Management or Capital changes them even down to the bottom of their souls where their life’s motors are set upon the piers of their foundation desires. This is the way often taken to get around the need of coming to the understanding of the other person’s actions by taking the tune to understand him. Of such study the result is pretty sure to be the same as that which impressed itself after my months at the south pole of the industrial world that humans vary little at the bottom of their hearts though they may vary much in the tops of their heads; that of all of us the mainsprings are just about the same, though different circumstances require different modes and methods of their escapement.

For some months I carried about the conviction of the enormous importance of the job to the wage-worker, as though it made him a very different and rather peculiar kind of chap till I awoke to the realization that in this industrial era of ours the job is almost equally important to everybody else. After all, there are exceedingly few of us in this country whose first concern is not our job. For almost all of us the most important part of our income, by far, comes from the carrying of some current responsibility, with serious trouble camping down very close to us the moment something goes wrong with that source.

Even the industrial captain builds up his capital quite largely to take care of himself and his family in the days when sickness or other disability puts an end to his yearly salary as the busy director of this enterprise or that. The chief dollars-and cents difference between his job and that of the workers in his factory is that he is more likely to be hired and paid by the month or the year instead of by the hour, day, or week and to have certain securities against unwarranted discharge. Upon him as upon the worker hangs always heavily the fear of lessened income as the result of sickness or death of joblessness. His abilities and his savings lessen the fear, of course, but do not by any means eliminate it. Most of the difference, then, consists, not in his being in the group of management, but in the size of his margin of security and safety a margin given him by his closer connection with those who give the job or take it away and by the larger savings and assurances which his larger education and earnings permit.

In the work of the Cleveland Welfare Federation we spent large sums trying to get the people of the city to understand that the community’s poor were not a fixed group or class habitually acting from abnormal and peculiar motives and therefore habitually and permanently in need of help. It is this difference, not of human material but of educational economic margin, which permits some to save themselves while others, encountering the same obstacle of sickness or unemployment, are brought down to the need of temporary help, just as a friend of mine reported: “I’m getting old. Ten years ago I could stumble and still keep going for fifteen feet at least. Now a stumble means a fall without doubt and without delay.”

The difference is in the margins of assurance, opportunity and living in general, allowed by the daily or weekly wage instead of the monthly or yearly salary it is this that gives the reason of the labor gang’s intenser and more necessitous attitude toward the job, rather than any or all supposition that the gang is made up of humans possessing different interests and therefore wanting satisfactions entirely different from the rest of us. During the long hours of shoveling bricks, lifting the steel sheets off the cold rolls, or stenciling the “Regular weights, there now !” onto the barrel-heads, it was often a problem to know what to do with one’s mind.

On some such turns I would definitely try to make the time go faster by picking out some particular field of recollection and endeavoring, hour after hour, to “lick the chops of memory” by recalling every impression possible, for instance, on one shift from my travels in Italy, on another turn Egypt or South America. At other times I would find myself swinging my body in rhythm with the movements of the job while almost chanting to myself: “I wonder if anybody could ever find any connection between this town’s evident immoralities and some of the plant’s evident dissatisfactions?’

“Is there any connection between the way people earn their livings and the way they live their lives? and if so, do bad morals cause bad jobs or bad jobs cause bad morals, or both?” As becomes a father, my fondest hope is that the following offspring of my long-turn ponderings may prove a more helpful interpreter of our modern industrial life and all its human units than that offspring of the philosophers which ought to be known as the “economic alibi.”

Suppose we start at what might be called our “jumping on” place there in the shining land of Get-up-in-the-morning, and draw a line through the sixteen waking hours of our day to the “jumping-off” place there in the shadowy land of Go-to-bed-at-night. Such line we may quite properly call our “western front” at least it represents all the opportunity we have for the putting forward of all our life’s campaigns, whatever and wherever they may be. Now, from all that I have seen or heard all kinds of human beings do and say, it is safe to assert that every normal person possesses at the bottom of his heart the desire to find somewhere along this front the satisfaction that comes with the consciousness of “breaking through.”

It is impossible to conceive of anyone who would pass along this front day after day, and year after year, without getting anywhere some feeling that he is making progress counting as something more than a cipher in the sum total of humanity and be therewith content. Such a person is pretty certain to be proved an imbecile or a fool or else he will be found among the unknown derelicts at the morgue. Now, in these recent days of unrest and commotion, when fear gives birth to misunderstanding, and misunderstanding increases the brood of fear, it is easy for all of us to believe that the man who is too far off up the line, or down for us to see and know him, will not be satisfied unless his “break-through” brings him into the manager’s or the autocrat’s or the plutocrat’s chair of absolute power for the domination of the rest of us.

Yet acquaintance with both groups is sure to convince all as it does me that the member of the labor gang is no more truly represented as the father of such an extreme desire than is the capitalist though such acquaintance does show that each is willing to believe the other not only capable of such a desire, but happy in it. It is immensely truer to the actuality to believe that every normal person, quite apart from his particular membership in this group or that in the industrial process, is moved to do what he does by the universal itch to feel that somewhere on his life’s front he is justifying his existence among other persons by ” getting on,” doing a little better than merely holding on, while those about him pass along. In this feeling all of us find quite as much pleasure in beating our own previous record as in going ahead of others. The main thing is the sense of motion and progress.

When the “high spots” of the “boss roller” or the “first helper” are put alongside of the successful banker’s or manufacturer’s it is odd to observe that they all fit into practically the same formula each is a high spot because it serves to measure their progress from the point where they started. It is this satisfaction in the distance traveled rather than in the point arrived at, that permits millions of us to have our separate, individual satisfactions without wanting to crowd each other out of the pleasure of the same, or competing, ultimate destination.

Thus: “Well, yes, things have gone pretty well with me,” says the nationally known philanthropist, the boss roller, or the first helper, as he reaches expansively for his Havana, his pipe, or his quid, according to station and fancy. “I’ll never forget the day and, yes, the hour, for I happened to notice as I went in that it was o’clock when the boss sent for me from out of the labor gang” (or the office force, or other position without especial distinction), “and asked me if I didn’t want to take a try at – ” (fill in name of next position up the line).” Then I recall that it was just years ago this next month that my new boss proposed,” etc., etc. (fill in all the steps which indicate distance travelled from the point of starting).

Altogether, it is very fortunate that the great majority of us take much more satisfaction in passing the “flivvers” of our past, or the truck loads of our slow-moving associates, than we take dissatisfaction in the thought of the limousines still ahead of us and still unpassed on the road of life and progress. All things considered, we could hardly hope for progress from anything less selfish or for self-preservation from anything less progressive. Now I am convinced that the daily wage-worker wants, to an even greater extent than the rest of us, to find his high spots and locate his break-through in the sector of his job.

For one thing, the narrowness of the margin between the daily job and the daily bread means that what he does in the hours under the plant roof determine more narrowly what he may do elsewhere, than does the nature of our work for the rest of us; and that is saying a great deal, for in a world built on jobs, all of us must adapt ourselves first to the conditions which we must meet for the earning of our living, and then, with what we have left of time and attitudes and interests, set about the living of our lives. If the worker is still on the long-hour day, all this can be figured out in minutes to make plain the immense necessity of getting the utmost of personal satisfactions out of his working time.

That means that the worker lives and moves and has his being there on the job. There is where the tire of his life’s wheel meets the smooth or jagged roadway of actuality. But still more important than that, he finds there in the precise nature of his job, skilled or unskilled, important or unimportant, and in the relationships it provides, the most important means of establishing his status and standing as a man and a citizen and the status and standing of his wife and children. Thus the oil-can or the wrench spells progress upward from the shovel, quite beyond the two-cents-hourly income. Thus, too, the promotion out of the gang to the humblest foremanship is certain to mean not only more money for a wider margin of enjoyments and securities, but also, and much more important, the envious congratulations of the gang, the familiar acceptance as a comrade at the hands of others heretofore far above him, and, finally, those gossipy noddings of heads at the club or the lodge which are the incense burned before the altars of progress and success.

It is only the great distance of most of us from such events that permits us to miss the hugeness of these steps as they appear from the view-point of the labor gang. It is this hugeness that causes many workers to lose their heads certainly, at least, the natural size of their heads the moment they find themselves thus elevated and so perhaps inclined to drive their former “buddies” with less consideration than that shown by those who never were in the gang. Now in view of all this, the most fundamental criticism I know how to make, in regard to the present industrial situation, is this: that in the minds of so many members of the labor gang, and also of higher groups of workers, there is so wide-spread and so deep-set a conviction that for them there is no chance to break through on their industrial sector!

It must be evident to those who have read this diary that while the matter is two-sided, nevertheless, considerably more justification than could be wished is, as a matter of fact, given that conviction. The trouble the most manifest trouble at least is in that “first line of defense” which is maintained there at the contact points on the line by industrial management in the person of the boss or foreman, the plant guard or policeman, and the plant paymaster and his clerks. If the break-through is to be engineered on the sector of the job, it must inevitably be in” the presence, and with the permission and recognition, of one or more of these representatives of and of parts of the management.

Through these the workers must get those daily demonstrations of the plans and purposes of all the other “lines.” There would seem to be no way by which management can avoid the responsibility for whatever impression the workers gain of its performance and intentions as the result of those demonstrations nor any effective denial that that impression as a whole is considerably less satisfactory than could be desired. Whether justified or not, this conviction that on this sector no satisfying feeling of gain or progress is to be made in proportion to effort required that “pull” and the marrying of the boss’s daughter must be counted on for getting forward produces the same result in the factory as it would on the fields of France and Flanders. When Foch or Haig became convinced rightly or wrongly that successful pressure could not be hoped for, strategy and the necessity to keep moving required, of course, the transfer of the effort to another sector.

So today, when the worker becomes, in any way, convinced as the result of a few deadly demonstrations, that employers as a group are unwilling or unable to reward initiative, loyalty, and skill, he’ changes his tactics. Leaving behind just enough energy and skill to keep “the enemy” from “breaking through ” and discharging him and he’s a wonderful judge of the precise amount needed for this purpose he withdraws the reserves of his interests and enthusiasms for more effective and worth-while application elsewhere. Like all the rest of us, the worker, it is worth repeating, carries into the other sectors of his living the equipment he is able to take out of his job.

So here again he suffers from the narrowness of his margins. If he is untrained he must daily put a larger proportion of his entire physical equipment in his case, his entire capital into his daily givings for the benefit of the needed daily gettings of the family’s food than do the most of us. Unskilled, skilled, or semiskilled, if he makes iron or steel the chances are that he must put in an average of twelve of those sixteen waking hours with, in most cases, an additional hour and a half or two to go and come. The result is not favorable to such a worker’s finding in, say, the sector of his home the sought-for satisfactions of forward movement and distinction. That is certainly evident from the most casual reading of the foregoing pages.

Over into the sector of his relationships as a citizen, similarly, many a worker can take only a depleted physique and an unsatisfied hope. Some, however, do “stand the gaff” of even the hardest work and, perhaps with the help of a sense of humor or a determined will, endeavor here to find the distinction of leading those around them. I am quite sure that these are often the men whose manifest ability to influence others comes to the attention of the all too common plant detective or “under-cover man” with the result that they may be reported as potentially dangerous workers. In too many instances such a report is likely to lead to the “planting” of, say, a bottle of whiskey in the man’s clothes, with the later discovery of it by the secret planter, who in horror at such outrageous breaking of the plant rules, lands the offender on the street, jobless and sore, ready to believe that his manhood requires his personal direction of a continuous war against the industrial and economic arrangements which permit such injustice.

I have reason to believe that such men are not happy in their capacity as leaders of the war that they would be enormously happier if they could find there in the plant and on the job the opportunity to enjoy the sense of constructive leadership which, of course, remains unattainable until the hurt that honor feels has been assuaged. It is strange that so many managers who themselves get great pleasure from their membership in some committee of the local Chamber of Commerce find it so difficult to understand the wish of some of the workers to enjoy similar distinction in their world under the plant roof.

Into the final sector of their miscellaneous relations as a person come great numbers of workers who realize their position at the base of modern industry, yet who have found nowhere else in home or club or lodge any milestone of distance traveled from the starting point of personal insignificance. Here is their final chance. Of such men their profanity, I am persuaded, is intended to convince their hearers that they themselves remain unconvinced of the inferiority which their present job may indicate in much the same way that a child assures you of his ” I don’t care! I don’t care!” when his toys are taken from him. In addition, he can hope for a certain distinction among his pals by giving the requisite attention to the luridness and daring of his blasphemies. Of such men, too, their boastings of their “fifteen, sixteen w’iskee-beer” are also calculated to impress themselves and their friends with the remarkable carrying or staying powers of their physical manliness.

For many, further, the certainty with which drunken ears are able to hear the assurance of their owner’s achievements, past, present, or future, makes it worth while to indulge in the cup which congratulates as well as inebriates congratulates because it inebriates. The old machinist who used the bartender’s dispensations to “get the feelin’ of my old position back like, you know,” and the melter in the Western steel town for whom the “hard stuff” almost instantly recalled the days when he was discharged because “the boss he knowed I knowed more ‘n a minute about steel than he did in a month,” as well as the hobo who used his whiskey as protection against the bugs and flies all these and others support, sorely, this proposition that the worker’s bottommost desire is to find the chief basis of his belief in himself there in his work, and that, failing this, he endeavors in all the other parts of his living to make the necessary adjustments.

Yes, I am convinced that there is a connection between the town’s jobs and the town’s morals or immorals. Through the hours of the morning on the new job or in the evening after supper at the boarding-house, we would feel each other out and do our best to impress each other with our “high spots” just as do two bond salesmen at the club or two society leaders over their tea-cups. This job and that, and its importance, this promotion and the other, especially this occasion or that when the worker showed that he understood his job better than did his foreman these are men’s “talking points” as they try to “sell” themselves to each other; these are the things they hold onto all their lives. The sad thing is that with so many workers the stock of these high moments runs out so quickly with the resultant drawing on the reserves of this or that drinking bout or this or that conquest of the other sex. In the wealth of detail in the features of that conquest it is all too easy to see that here at least the narrator feels that he has proved that if fortune had only gone differently he might have shown himself an outstanding salesman, or if fate had only handed him a dress suit instead of a pipewrench, the world might have been the better for a real statesman!

Instead of believing that vice is the overwhelming of the spirit’s forces by the body’s, we would come much nearer to the heart of the matter if we discerned in vice the energies of both body and soul combined / in an assault upon all the forces that oppose men’s having/ life and having it more abundantly. The harm of it is that the assault secures the hoped-for sense of victory the indispensable sense of victory only because it is made at the weakest spot in the line and so proves fleeting, false, and degrading. So that first line of defense does more than lessen men’s interest to break through on the job. It increases by the same amount the pressure to find on some weaker sector the gain that will justify a proper self-respect.

When all the fields have one after the other been entered and explored, there must somewhere be found experiences and satisfactions which will make the whole enough like the normal and average life of the normal average human to be properly called ” wholesome” else a man may not call himself a person. It is the fault of all of us to a greater or less extent if this craving for wholesomeness requires many men to vibrate back and forth across the line of the normal as from a restrictive job to a short but furious high spot of a vacation in order to feel that these extremes average into a fairly passable holding of the line. This ” wholesomeistic person” is interested in the pay envelope, but most of all he wants it to help him find in his work the justification for feeling himself a man because of what he does a man because a workman, a workman that need not be ashamed.

Much wrong we do him when we assume that nothing will satisfy him except the management and ownership of the entire enterprise. That assumption binds our hands because it blinds our eyes to the high desirability of changing his whole life as well as his attitudes and convictions by changing the possibilities for his normal satisfactions on his job. That change requires not only the improving of the foreman and the others he sees as the company, but also the lessening of the fear of joblessness, the ill humor of fatigue and the ignorance of the deeper motives of his associates in the whole industrial proceeding.

The harm that all these do is done because they so vitally affect men’s feelings. Built, all of them, upon the bottom wish to consider ourselves self-contained, self-controlled, and worthy personal units in the world, it is our feelings that lead us all to the release of all our energies. Our thinkings give us our facts and the logical connections between them. Our feelings enable us to set a value on those facts and connections. All the yeast in the world gives bread no value until the feelings of hungry humans speak and the arms of hungry humans reach. Short experience will convince anyone that it is impossible to overstate the influence on these infinitely delicate scales within us of a few days or weeks of joblessness, a few months of fatigue, or a few years of the conviction that the company doesn’t care and that doing the job ” don’t get you nowheres.”

So long as human beliefs and attitudes are so slightly the result of thinkings and so largely the result of feelings of hope and fear, fatigue, disappointment, pride, so long will it be worth while to see the cause of any man’s abnormal beliefs and attitudes in whatever abnormal conditions may surround his job. And here it must be noted that the normal conditions of a decade ago may become abnormal to-day, because they have remained while others changed as when, for instance, other industries shorten their day ‘and leave one or two to continue with the long turns. “You take the best-trained and mildest-mannered lion imaginable the result of a life-time’s careful handling and in five minutes of bad treatment which rubs him all the wrong way, you can drive him back into a wild beast and, perhaps, keep him there for life!”

In these words an expert trainer puts well another extremely important difference between feelings and thinkings. Ask a man how long he has possessed such and such an idea and you can make a rough judgment as to the probable difficulty of disproving it. But, by its intensity, the emotion of an instant may prove more effective than others which have been possessed for years. Thus a few months or even years of plentiful jobs do not by any means cross off those feelings of despair which burn themselves in on the soul during a few months or weeks of unemployment as in 1913-14, and to a less extent in 1919.

Thus, also, many employers and many union members find it quite impossible to-day to discuss each other without a heat which badly warps the straightness of their thinking, perhaps as the result of attitudes forged in the heat of intense emotions years and years ago. “Well, you see, he was the leader of the union durin’ the strike. A fair-minded man he was and a decent strike it was, at the start. But finally the company orders every family out of all its houses in eighteen hours everybody’s gotta be out, y’understand. Well, his wife, two days later, had a baby when they was campin’ out an’ died. He’s been what ye might call a company-fighter ever since.”

This was the report of a famous radical given me there in the second mine town. “No, I’ve never believed in the fairness of the worker or the unions since the time they went out on us after we had treated them the best we knew how for years,” was the way an employer told of his own hurt. “And they all acknowledged that they had no complaint!” “Well, what can we do?” said the workers in very much the same situation in another city. “If we don’t go out the boys where they haven’t got the advantages we’ve got can’t win. If we lose our jobs we can still keep our friends and live in the town here, but if we refuse to help our buddies make their fight, then we can’t go on living here that is, ‘thout bein’ called yellow. What’s the answer?”

Each is trying to solve his problem in the way that allows him to feel himself true to what he decides is his highest loyalties. Yet each fails to see the conditions under which the other’s choice must be made. And each is certain that the other’s action is made plain by that ” economic” formula of the philosophers. All of which means that in the world of human energies the “relativity of motion” holds as true as any Einstein may demonstrate for the world of natural forces.

If all of us stood still, then all of us could stand contentedly and “save our face” in standing. It is when war makes the unskilled worker into a munitions producer and puts him up the line out of his place that those who have not moved forward feel that they have in actuality been moved back, and are therefore unhappy. By the same token the profiteer is felt to have moved backward all those who would otherwise be perfectly content to feel that they had shared with others the universal set-backs of war times and conditions.

In the same way, too, men feel it proper to desire more progress in the way of better jobs after returning from the fields where so much blood was shed that all men might travel farther into life and more abundant life. As long as all these feelings for forward movement normally express themselves first of all in the form of pressure there on the earn-a-living sector, it behooves us to guard and protect them from every influence that disturbs them, unless those influences are found to be absolutely inseparable from the industrial process. Such disturbance as is to-day caused by the fear of joblessness, fatigue, and ignorance constitutes, I am certain, a very serious, costly, and needless brake upon both the self-respect and the effectiveness of our workers and fellow citizens in our basic industries added to by the further commotion caused by the war’s upsetting of old standings and statuses.

Before this latter can be ended it will be necessary for all to feel that something like the old relative positions and opportunities for the same relative motions forward have been re-established, with the bottommost moved up so as to meet the more particular measurements and requirements of a more democratic world. The process is trying. The very disturbance and commotion puts people throughout the country into the same touchy mood that followed my sleepless bed and crowded kitchen in the first mine town, because all these things reach and roil feelings even though they may not affect thinkings. Thereby the gap is widened.

If, then, the precise formula needed to bridge the gap comes not instantly to the lips, feelings are sure to be hurt, relations become strained or broken if, indeed, the war is not on the instant declared. But as long as men will fight oftener to save their face than to feed their stomach progress is assured as long, at least, as the public and the determiners of the conditions of industry understand the vastness of the forces which men carry in their souls and the delicacy of their control, and then arrange properly for the release of those forces. A word or two about such arrangements and we shall be done.

THE WAY OUT AND MANAGEMENT

If my opinions thus far are in general sound, it is evident that those who determine the conditions under which a man earns his living determine thereby pretty much the conditions under which he lives his life. This would seem to be supported by the fact that the whole circle of present day political and social as well as economic varieties of unrest unconsciously seek correction by attacks not on the social or political but on the industrial sector. By the strategy of the most practical and pressing necessity thus, as well as by the logic of our line of thought, the challenge of the whole range of our modern life comes to be deposited on the doorstep not so much of the owners of industry as of its managers. I am sure that most of the thinking and feeling which is going on at the top of the great industrial organizations is good enough to deserve better expression on that first line of contact.

Nothing is more certain than that this better expression will be worth all the effort or money it may cost to secure it. The average foreman’s failure at least in the fields I visited to obtain the worker’s desire to cooperate would be a matter for smiling if it were not so serious a drain upon the whole industrial process. The number is surely large of those workers who must smile in their sleeves when they think how easy it is to let a foreman suppose that they are giving all they have when as a matter of fact they have merely calculated to a nicety the amount required to save them from immediate joblessness. Such an artistic appearance of labor without its actuality is sure to be the result, whether the worker dislikes the boss or distrusts the company. In either case the company is sure to pay the bills though, of course, they are passed on to the consumer in the cost of production. Nothing is surer than that the company’s and the public’s bill for this failure of the foreman is colossal.

The foreman who fails to get the good-will and respect of his workers is pretty likely, also, to fail to make good use of the slender energies they do release. But it will always be difficult to get either persuasive or intelligent foremen for the handling of men on the long turns: tired workers require too much heat in their driver’s mouth to favor much light in his mind. When the shorter hours are put in force, management will make a most costly error if it does not exchange this driver for a leader with the ability to use for the best good of the company the energies he can interest his men to release. Besides huge inefficiency, murder itself is likely to occur if the old type of foreman tries to continue his old tactics with men no longer too weary to hope for the satisfactions of self-respecting work and accomplishment.

The need of lessening the foreman’s right to discharge a man at will without, perhaps, withdrawing it completely, hardly needs statement. Larger security on the job is the first requirement for safeguarding the worker’s self-respect. The better expression of company interests by plant policeman and paymaster’s office also needs no argument. But it must not be assumed by any means that the cause of the faulty expression lies wholly in these officials and their shortcomings. Just as the worker learns or thinks he learns about the company by this or that demonstration staged by the foreman, the guard, or the paymaster’s clerk, so the foreman must guess the kind of manner and message he must pass on down the line only by the demonstration of it he sees in the actions of the men just above him. Without doubt the worker’s wholesale and hard working explanation “Aw, he’s afraid he’ll lose his job!” is all too often the true diagnosis of the foreman’s conduct.

He cannot be expected to “put himself in the worker’s place” unless he can- be sure that he doesn’t lose his own place by so doing! And quite possibly the fault is not so much in the factory manager or superintendent above him as in the general manager above him or the vice-president or president or chairman of the board above him ! The labor gang, I am persuaded, is far from being the only place where men sigh to be given a greater chance to “turn themselves loose” without being rapped by a superior on the knuckles of their initiative. That better expression on the first line of contact, therefore, cannot be expected to favor larger satisfactions in the job until more “chiefs” assign responsibilities to all their associates as did one I have much in mind: “And finally this: Don’t bother to tell me how you propose to get the results we have agreed upon. That’s your job, not mine. But, in case your delivery of these results is interfered with by obstacles which you cannot move but I can, then have in mind that I try to earn my salary by sitting here with the door open waiting for you.”

If such words serve to send an executive out of the door with his head high and his heart resolved to give its utmost, there is small reason why their spirit cannot be extended clear down the line. At any rate, only when that is done will industry know something of the efficiency of the willing bird which flies farther than the thrown stone.

Meanwhile, this plan and that for solving the labor problem is discussed for weeks and months while the foreman continues to judge that he had better make his own job a little surer by passing in, as his own, the valuable suggestion of one of his gang, and then the “super” judges that he had better make a little surer of his place by passing it on to his superior as his! And no one can question the wisdom of their judgment until he knows how deeply or how superficially the president and the board of directors have thought about this matter of getting men to do their best. It will be recalled that the finest shower-baths I met were in the refinery for the use of the men under the control of the only person I have ever had the least desire to murder!

To the same effect is the general understanding that a company known recently to have inaugurated profit-sharing continues to employ foremen who make the workers pay them for their jobs! These words are not meant to discourage the initiation of plans and devices for the bettering of conditions and relations. The point is, that these must not be expected to lessen by one jot the necessity for fairness and squareness in all the relationships of the entire establishment nor, similarly, the necessity for improvements which save sweat and strain directly on the job where the work is done as in the case of the heavy sheet-bar there by the pair heater’s furnace. Instead of hoping to build a relationship of friendliness by means of the service or employment department’s restaurants, clubs, badges, etc., the purpose must rather be to help the entire organization to carry up and down, without obstruction, all the impulses which may be contributed by any at the top or at the bottom which are calculated to increase the effectiveness of any for the benefit of the whole. In these days of the multiple-unit enterprise, management is failing to offer to all kinds of workers, at top and bottom and in between, the assurances of a break-through that will be proportional to effort because it is failing to give proper thought to the development of those spiritual forces of its persons which are, after all, its final resources; and to the effective projection of these into every nook and cranny of the organization.

That can hardly be accomplished, though it will be helped, by a few classes for foremen. That can also not be accomplished by foremen or workers or executives who are supposed to be kept at their best by the fear of dismissal, instead of by the hope of increased opportunity and security. A discouraging feature to-day is the number of executives who depend entirely for their knowledge as to whether the projection of their interests and ideals actually reaches to the labor gang, upon the highly prejudiced testimony of the foreman or the highly unreliable report of the ” inside man” who makes his living by deception and who stands to lose his job the moment he fails to disclose a certain amount of trouble and unrest around him.

The result is that the worker’s ignorance as to the real heart and purposes of his employer is equaled only by the employer’s ignorance of the real wants of his workers. If it were not so, more employers would have confidence to ask the workers themselves to tell them what is on their minds and then see that nothing happened to them for telling. One reason why this is not done more generally in industry is that the manager is inclined to miss this point of the importance of feelings and so to rely upon his thinkings. Especially if he was once a worker, he is likely to think that his reasoning powers, by which he believes he has built up his business, will tell him what the worker wants even better than the worker himself can do it. The result is fairly certain to bring later disappointment to him and soreness to the men.

He should hang on his walls the “Eleventh Commandment,” “Thou Shalt Not Take Thy Neighbor for Granted.” Another reason for delaying so long the asking of the worker for his opinion in matters, not perhaps of finance or sales, but of the job and its conditions, is fear, fear that the worker will take advantage of the occasion merely to put more into that pay envelope. But except under conditions which appear to him to justify a sense of injustice or distrust, the most his self-respect will permit him to ask for is whatever represents at one and the same time the best interests of the company and of himself.

Where, therefore, this spirit of reasonableness is not in evidence, management will do well to seek, and seek diligently and deeply, for the abnormal conditions or relationships which are sure to be at the bottom of such abnormal and unreasonable feelings. In this collective dealing whatever may be its particular form the worker, if he is young, wants a larger opportunity to show what he can do with the assurance that it will get him some kind of proportionate recognition. If he is old, he wants a larger security for the holding of his job and his place in the line of job importances and standings.

In both connections he has something to give in return for these gains. He knows the exact amount of energy he puts into the job and how much he might put into it also how much more he could make what he puts in count, if somebody would make it worth his while. In one company now finding that it can pay better wages and still make steel more cheaply on the short day than on the old long turns, the men have helped largely to this end by contributing of their store of this knowledge of the job. As a result this job or position on the furnaces or rolls has been eliminated and that one has been combined with another for the saving of a man. Another thing the worker can give is his understanding of some of the difficulties of management and his resultant increased respect for management’s inability to work out all matters to everybody’s instant satisfaction. Of such understanding in these days of restless labor, freight tie-ups, and tight money, management needs all it can get from anyone but most from the worker.

It might be claimed that the worker, as a matter of fact, ought to want more than this for which he feels willing and able to give return. But with a larger chance to enjoy the satisfactions of a steadier, better job, with less stealing of these satisfactions by the foreman, he will be found to grow in ability and capacity to the same proportionate degree that the rest of us grow under the same stimulus namely, the necessity of “making good” by successfully meeting, one after another, the responsibilities of our jobs.

To anticipate without fear the gradual development of a partnership based upon the development of abilities and capacities requires nothing but mutual confidence in the fairness of each side. Such fairness any one is certain to find easy of expectation who has taken the trouble to add to his belief in the fundamental wish of the average manager to play fair the further belief of the worker to base his own self-respect upon the same honest foundation.

Each group must have a certain amount of consideration in understanding that the other is sure to be having its own troubles in molding the actions of all its members into that consistency of performance which is required to establish the kind of character that begets confidence. The shortcomings of this kind that exist in the past of both groups complicates enormously, it goes without saying, the possession of either this expectation or consideration unless they can be cancelled off against each other. All of which means that there can be no easy way out of the industrial problem. The reason is that that problem is a problem of relations between persons all of whom are daily forming and reforming their attitudes and hopes and beliefs and wants and faiths and fears on the basis of what they see or think they see, what they think, and especially what and then doing their best or their worst accordingly they feel. For which reason it is difficult enough to work out satisfactorily the relations between two perfectly friendly and perfectly expectant and considerate individuals.

Naturally enough it is sure to be enormously more difficult to work them out between great groups all of whom are bound, more or less, by their group loyalties, their economic necessities, and their economic and physiological margins to say nothing of the further difficulties of comparatively sudden gatherings together, strange confusions of tongues, and feelings that require that interpretation which often serves only as a “compound fracture of speech followed by mortification.” In such circumstances, it behooves each group to look with such forgiving eyes upon the inconsistencies of the other’s behavior as it would wish to have the other look upon its own. Both must face the demand for better collective morals before they can expect success as either corporations or as unions. These necessities and restrictions mean, for one thing, that there cannot possibly be enough promotions to go around, even when management equips itself to recognize ability wherever it discloses itself. But not all workers want promotion.

An immensely greater number do want to have a better idea of what the job is for. Huge numbers work year after year making parts of machinery without ever seeing the completed whole of which they have the right to feel themselves the co-producers and co-creators. Greater knowledge of its service to others makes my job better because more important. And the possession of a better job to-day than yesterday entitles me to think of myself as a better man. Luckily industry is awakening to the importance of this, as in a factory where movies are used to explain why a motor works to the workers who day after day make the motor’s parts. Along such lines there are almost endless opportunities for increasing the worker’s understandings and abilities without requiring the larger imagination called for in the more theoretical classes unrelated to the job.

Better jobs and steadier jobs, less tiring jobs, jobs whose human service is better understood, jobs with a better chance to enjoy the satisfactions of their doing without these being lessened by a grasping foreman representing an unknown employer: this is what the worker wants more than he wants to sit in the chair of the manager or clip the coupons of the owner. The challenge should not be too much for the American executive. Certainly he will find a greater satisfaction and perform a greater service in the meeting of it than ever he has known before.

A few decades ago the mass needs of the world called for the mass production of the great corporation. The need was met by the executive who was trained in the assembling and marshalling of the dollar in armies large enough to supply the power of massed finance. After him came the leader who possessed the ability to develop and direct men’s desires and demands in a way to furnish the organized mass sales required for the mass production made possible by the massed dollars. He in turn has been followed by the expert scientifically trained to secure the refinements in mass production which massed demand and competition made possible and necessary.

This executive still has some distance to go before we can talk legitimately about that science of industry which stands for the organized knowledge of the natural forces it employs. To-day the interests of the owners of the dollars which created the plant, and the originators and possessors of the desires and needs which keep the plant going, have the right to ask that the present-day executive give deeper thought toward developing that art of industry which will stand for the organized emotion of its human factors and forces organized and applied in ways which will at one and the same time meet most effectively the needs of both the makers and the users of goods, both the performers and the receivers of services. But if the manager is to meet this challenge of bringing about a better America by means of better jobs, he has the right to ask the cooperation of his customers in ways which, finally, are worth mentioning.

THE WAY OUT AND THE PUBLIC

Recent events throughout Christendom are calculated to make plain the interest of the public in this problem of the relations between those investors of brawn, brains, and bullion who comprise industry. To this interest the public is not hesitating to give voice in the form of its demand that ways be found whereby these relations can be composed with less general inconvenience and annoyance. This demand is not likely to be satisfactorily fulfilled until the makers of it see that it involves certain serious responsibilities. One of the most outstanding of these appears to me to be the organization of machinery for getting the worker and the job together.

Both industry and the public have to pay too high a price in the shape of the wasted opportunity of the unmanned job and of the injured morale of the jobless man to allow the getting of the two together to remain in the hands of the employer who likes to have forty men at his gate for every five jobs, the union which may similarly wish to juggle the market, or the job agent who puts money in his pocket every time one of his patrons is hired and, by the same token, fired. Nor can this function be performed well by a government department which, in the nature of the case, is compelled to favor the worker more than the work itself or the employer. This is practically the situation of the Department of Labor according to the terms of its establishment.

There should be no reason why that department and the Department of Commerce could not jointly be authorized to set in motion an interstate employment bureau which would facilitate the transfer of men from one part of the country to the other without the over-emphasis of one group’s interests or the over-centralization of authority which hobbled the recent federal bureau. Beyond doubt such a joint bureau should ask and receive the support of manufacturers, workers, and public in making at once a study of all the obstacles in the way of the maximum regularity of operation of all industries. In such regularity the wish of the owner meets the wish of the manager and the worker: all want steady work, whether for their dollars, machinery, and plant, their directing abilities, or the energies of their hand and arm and head.

Without doubt, too, such a study would not get far without seeing that the public has a chance to play a large hand in aiding this desired regularity, or in insisting that men shall not work themselves out of their jobs. It is well known that extremes of style tend to overwork men and women part of the year, and then to out-of-work them a larger part. Seasonal buying of such things as coal naturally puts upon both production and distribution the same strains of rush-hour peak loads with the consequent depressions that daily embarrass the transportation systems of cities. This strain seems to grow rather than diminish as the users of, for instance, railroad or manufacturing supplies tend to come together into larger and larger aggregations of buying power. Such aggregations present, however, the means for securing the hoped-for improvement with greater ease, when once the solution of the problem is seriously approached. Such aggregations and government could also co-operate to make the hobo no longer necessary by fitting seasonal jobs together in ways to avoid the need of migration.

Whether unemployment insurance as operated in other countries is to be considered or not, there is no question but that such a study of the obstacles is desirable in itself from every point of view before the public can think intelligently of getting at both of these corner-stones of the whole industrial problem the getting together of the man and the job, and the keeping of them together as long as is efficiently possible. If government cannot represent the public interest in this way, it is to be hoped that some group of enlightened employers may set about it in an unprejudiced and scientific manner, with, if possible, the cooperation of these workers.

The most important result of such studies and the organization that would follow them for increasing the regularity and the security of the job would be this: it would force the foreman and the whole managerial organization to abandon the all too general practice of capitalizing the fear of joblessness, and to organize for getting a much greater co-operation from the workingmen by means of a constant appeal to their faith in the surety of reward. Until some such fundamental change as this is made there can be but futile talk about the moral or progressive values of good character in connection with the relations between industry’s persons either as individuals or as groups.

Without this change, furthermore, industry will remain far behind education, religion, and salesmanship, all of which have in our day substituted for the old appeal to fear of punishment or penalty the appeal to hope, and faith in a proportionate reward. It is a question whether any plan such as that of the second industrial conference will serve to inform public opinion as well as one organized to give to all the facts of industry a continuous and unprejudiced study and interpretation without waiting until the situation is acute and those in the middle have come to share the prejudices and biases of one side or the other. But many plans will doubtless be found worth trying and will be certain to contribute some bit of guidance to the better step.