Foreword

The MitM transposition experience can only take place with the keystones in the hyper-learning setting. That means getting to Plan B status is not a solo performance. The MitM engaging the FLLP is surrounded by his fellow keystones going through the same process. It is a social metamorphosis.

The walkthrough follows a packet of keystones (apprentices) travelling together with the interventionist (master) from Plan A towards Plan B. No others are in the setting where hyper-learning takes place – a stop-rule provision.

The interventionist does all the upfront work. When the stop rules are issued, he begins one-on-one visits with every member of the keystone group, in situ at his workplace. Personalization by the interventionist, before the episodes start, is part of high-stakes trust building. As in all hyper-learning, the FLLP runs on a mutual-trust basis. All else fails.

The walkthrough follows the Plan B sequence of learning. There are three major milestones along the path to the payoff; restoration, implementation, and accumulation. The focus at any slice of time is always on getting to the next milestone, nothing further. Each journey between milestones is its own unique challenge, structured by the Ackoffian Triad. Getting to Plan B is not one seamless campaign but a series of bite-sized campaigns in tandem, each one building upon the previous attainment.

Since no website can provide the necessary hyper-learning setting, have no expectations for reaching Plan B via documentation alone, hard-copy or electronic. Getting to the Plan B state is a sprint, not a marathon, and a pole vault.

The tilted playing field

No transposition from Plan A to Plan B begins on a level, neutral playing field. H.S. Sturgis, a century ago, described the leak, lag, and friction in the starting situation. Nothing has changed.

One of the important by-products of sound departmentalizing is the reduction of frictional losses by bringing together into close working contact within any department only those people who tend to be likeminded. To be sure, risks of smugness and stagnation / are increased by too much like-mindedness, but these risks arise chiefly when there is lack of intensity of purpose or need to achieve. When an organization and its members feel such a pressure, the dangers of smugness are small. Conflict and losses of power arise when ultimate aims are different—when the members, to a greater or less degree, work at cross-purposes.

Organizations very strongly departmentalized and weakly coordinated usually contain all varieties of difference in aim. Where an organization is run on the classical “hire-department-heads-and hold them accountable for results” plan, there will be a great deal of conflict and friction. Successful showings for a single department may be attempted by putting over something on another department, or even by definitely handicapping its work.

Some years ago an investigation in one relatively small company disclosed that every week there had been dozens of smart tricks played by one department on another department, much to the detriment of the organization as a whole. Frictions and conflicts are overcome as everyone’s aim becomes more and more to find the right way for the whole organization rather than to have his own way, that is to say, as progress is made towards the development of a common purpose. If everything two parties want is different, if a Labor Union, for example, wants only high wages and favorable conditions, and the employer wants only low wages and production, nothing is possible but conflict— or a keeping apart.

Working together demands some area of common will or mutual interest. There cannot be more of it than that area allows. Organization engineering must always be trying to make the most of the areas of mutual interest that already exist, and attempting constantly to increase them in size, as well as to develop new areas and to remove or reduce the areas of conflict.

Friction can arise also when rates of working speed or of progress are different. Slow workers and fast workers do not get along well if close together unless there is unusually good lubrication through high morale and strong traditions of mutual courtesy and consideration. There can never be perfect evenness of tempo among men, but in grouping men into gangs or bench mates, extremes can usually be avoided. It is only the greater differences which are ordinarily of enough importance to demand attention from the organization engineer.

It is not often that the introduction of speeders into a gang will give good permanent results. They may increase output, but at too high a cost of /quality or morale. In a group of executives one who is too far beyond the others in ability may offset all of his own good work by the frictions he engenders, unless he is extremely tactful as well.

Friction arises from a lack of common understanding also. Each man has a different life history from every other man, and his necessary preconceptions are, therefore, different. Yet it is upon these as a basis that he must interpret the “facts” he seems to see about him every day. Hence, there is a definite value in personal /acquaintanceship among members of an organization; and particularly among the members within each department of it. No one can get fully into the game in a team whose members he does not know personally.

Salesmen’s conventions and visits, general field days, and departmental get-togethers, have as part of their value the hastening, broadening, and deepening of acquaintanceship, and the lubrication of frictions. It is because a sufficient understanding can seldom be built up by correspondence that frictional losses so often occur where the only contact is through letters. These frictions have been quite common between factory force and selling department, and between the field and the head office in government service.

Among men not incurably incompatible, sufficiently frequent face-to-face contacts will help in the development of smooth cooperation; in all forms of organized activity working together is the best way to learn to work together.

The structural form of an organization may itself increase or decrease the chances of internal conflict or friction. One of the most common examples is a rigidly enforced straight-line organization in which little or no communication is allowed, except step by step up the line, and step by step down again.

When frictions are due to structural form their real causes are difficult to discover, and especially difficult for the men at its head. They look down the lines of authority and see them straight and smooth; they know that problems travel up along them and get ironed out.

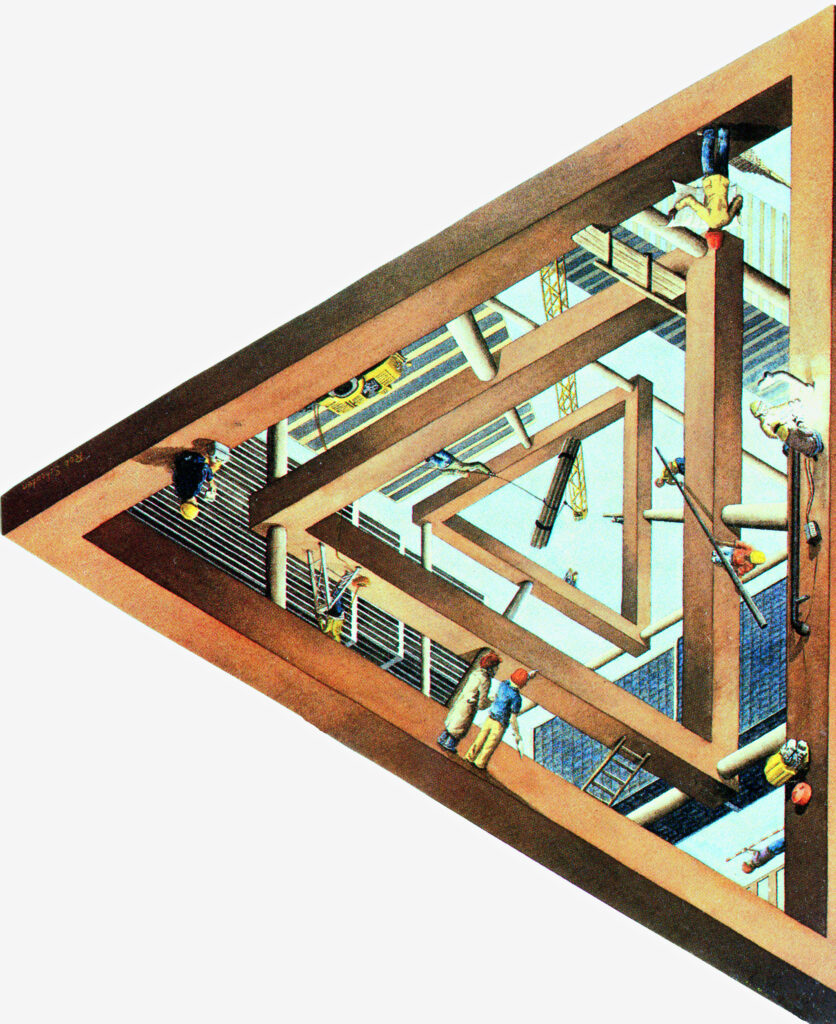

Lines of support look delightfully free from complication, and activities have an orderly appearance that gives an impression of efficiency. But when one looks from below, one sees an entirely different structure. The various functions are, in fact, interdependent and at these points of interdependence friction, waste, and duplication occur.

The man below knows that not all problems travel up the line or get smoothed out; he looks across the lines and sees friction and confusion. Contrary to an almost universal feeling, occasional “going over the heads of supervisors” is a necessity fundamental to good management. Of course, in any proper organization, no man, for example, in Rank 2 of authority would give orders to a man in Rank 4, when it could be as effectively done through the Rank-3 man, and never without telling the Rank-3 man precisely what he had done and why,, which jump a rank, are not often necessary in a well-organized concern; more frequent is the chance for the Rank-2 man to give some help to the Rank-4 man, and to learn something about him and his work from first-hand observation.

Under appropriate conditions, moreover, and with proper safeguards, the Rank-4 man should be encouraged to go direct to the Rank-2 or Rank-1 man, over the head of his immediate superior, to put his case direct.

While delicate situations may result, they should not often occur unless the organization is seriously defective. The greatest sensitiveness about “going over heads” will be found where there is no measurable degree of mutual understanding among members of an organization. Where a real mutual understanding and considerable areas of mutual interest exist—where what Miss Follett has called “the law of the situation” rules rather than individual caprice—there they forget the phrase and even tend healthfully to forget the word “heads.” Internal conflict can seldom—and then only temporarily—be overcome by arbitrary compromise. Ordinary compromise is too easy and too artificially simple to be adequate to the complexities of modern organizations.

There must rather be a painstaking analysis of the general and special interests involved, followed by an integration or synthesis which makes the most of the common interests and the least of the divergent. Frictions, where they cannot be overcome, can be lubricated by modifications in the means and methods of the daily work. In both business and political organization “playing politics” is at times legitimate, if by the term is understood the determination of actions by “what people will think.” What to do should be determined by consideration of the total situation and an estimate of what action will be most effective in it. What to do is to be settled by what it is right to do. How to do it—and often when to do it—should take into full account the opinion of those affected.

Whom to advise with first, whom to notify, how to say it, when and in what setting to act— these are “political” questions. What is right to do is the first question to be settled, and is ordinarily in a business not political. They are no substitute for real cooperation and an organization depending wholly upon them will have little force; but courtesy, tact, and consideration can prevent the occurrence of petty frictions and prepare the way for the development of true tolerance and objectivity.

Modern developments in the subdivision of work tend to reduce opportunities for individual craftsmanship. Yet there may turn out to be a joy in teamwork—a delight in a joint product—equal or superior in driving power to all but such superior craftsmanship as would approach the grade of artistry. It is worthwhile, therefore, in any study of organization engineering to make thorough analyses of the characteristics essential to teamwork, significantly called, also, “team play.”

In a rough preliminary analysis there can be found necessary factors, all of which must be present if there is to be success. There must be on the part of each member:

A Knowledge of a Common Purpose.

Make common knowledge possible as a basis for the adoption of common ends. A valuable possibility of a works committee is the development of an understanding of whatever area of common purpose may exist. Obviously, secrecy and suspicion are fatal to any thoroughgoing knowledge of a common purpose and, therefore, to any desire for it. For effective teamwork this knowledge must be definite, not simply vague and general.

A Desire for a Common Purpose.

This desire when aroused may range from a very mild approval to fanaticism. Where it exists, individual interest will be deepened by the knowledge of the sympathetic interest of co-workers.

A Desire to Help Each Other.

This appears to be the primary distinguishing mark of teamwork.

It is only the organization which must perform a variety of duties that would be likely to be called a team. If the group were merely in lockstep and all had just the same thing to do, we should not think of it as a team. Clearly, the tackle must know something of what his quarterback is supposed to do if he is to help him. He may not know how to do the quarterback’s job, but must know enough about it to offer some compensating aid when it is needed.

The credit man likewise must know something of the salesman’s problems and the warehouseman something of the production man’s problems, if they are to work together. In close knit teams like small erection or assembly gangs, where the members are in constant contact with each other, each knows by observation how well the others are doing their jobs at any moment. It is more difficult to get teamwork in a wide-flung organization of salesmen.

There it is necessary through such devices as group meetings or conventions to make this knowledge available. To get anything like coordination between selling and factory, it is usually essential that there should be a good deal of traveling among them—salesmen coming to the factory at intervals, factory foremen and department heads going on trips to the selling field. To know how to help teammates it is necessary to know something of their temperaments, to know, in other words, the spirit with which they are doing their work as well as the techniques they use in doing it.

Preparing for the FLLP

The long history of management abuse of foremen makes the stop rules a necessity. Management can be trusted only to behave as groupthink management. It rightfully fears foremen becoming aware of the intrinsic social power the foremen have, conveyed by their role, to determine the prosperity of the organization. As experience teaches, the critical point is reached when management learns the FLLP is delivering its promises. Management will either stay disconnected, as required, or break the stop rules, ending the FLLP. As PEs, in this situation, the conditions of our license require withdrawing from the engagement.

The “Front End” scope of work by the interventionist, necessary to run a successful FLLP, is critical to Plan B installation. He arranges for the hyper-learning context and secures management “acceptance” of the stop rules. Nothing takes place with the MitMs until the stop rules are in place. The interventionist is in it for the outcome, not the income.

All MitM participants in the A-to-B process enter the learning arena as psychologically-damaged goods. The milestone after the front end is to restore the MitMs to the open-minded, inquisitive condition they were born with. The subject matter to be injected into the MitM class via hyper-learning follows the need to reach the next milestone.

This knowledge is injected in phases into the MitM vectors-in-restoration by the interventionist during the FLLP. Many of the items marked Ḧ are known by the MitMs, but generally undiscussable in Plan A conditions as Ḧeresey.

- Top priority in Season 1: Episodes 1&2

- High priority in Season 1: Episodes 3-6

- Introduced in Season 2

- Peripheral

Ḧ- Heresy

Top Priority – 1

- Rogerian triad, personalization ❶

- Platinum rule ②

- A network phenomenon ❶

- Autonomous desynchronization ②

- 2½ rule ❶ Ḧ

- Limits of management scope ②

- Great divide ❶ Ḧ

- Delusion implementation ❶ Ḧ

- Yin/Yang attractors ②

- Abstract tangible ❶

- Subconscious rule-based v conscious performance-based ②

- Mentor line ②Ḧ

- FF ❶ Ḧ

- Value systems of groupthink management ❸

- Reaction to Plan B ❸

- The A-B Delta Chart ❶ Ḧ

- The 2nd Law ❶ Ḧ

- Entropy Extraction ❶

- Infallibility ❶ Ḧ

- Groupthink Ḧ

- Information quality ❶

- GIGO ❶ Ḧ

- Opacity v transparency ②

- Lies ②

- GIGO ❶ Ḧ

- Hyper-learning context requisites ❶ Ḧ

- Power ≠ authority ❶ Ḧ

High Priority – 2

- Natural laws ②

- Gödel Einstein ②Ḧ

- Control theory ②Ḧ

- Stability laws ②Ḧ

- Gain ②Ḧ

- Ashby ②

- POSIWID ②

- Shannon communication ②Ḧ

- Systems think ②

- Incontrovertible, failure proof ②

- Ackoffian triad, front end ②Ḧ

- Activities in Plan A absent in Plan B and vice versa ②Ḧ

- Responsibility/autonomy ②Ḧ

- Intelligence amplification ②Ḧ

- Innovation amplification ②Ḧ

- Ca’canny ②

- Subconscious mind attributes ②

- Recidivism Nash ②

- Stability laws ②Ḧ

Season 2 Priority – 3

- Inalienable rights. Psychological success ❸ Ḧ

- Subconscious ❸

- Gatekeeping ❸

- Triage ❸

- Negative characteristics ❸

- Warfield’s dictum ❸

- Connectance ❸ Ḧ

- 36% Turnover Rule ❸

- Social conditioning ❸ Ḧ

- Legal ❸

- Conditions of license ❸

- Deliberate ignorance ❸

- Crimes of command/obedience ❸

- Stop rules, professional license ❸

- Endocrine/immune systems ❸

- Plan A MoA history ❸

Peripheral

- Leadership

- Credentials

- IQ

- Morals, ethics

- Golden rule

- Tradition

Salute to the Kernels

The kernels collections are the topics infused by the interventionist as the FLLP progresses from Restoration to Implementation and on to Accumulation. The interventionist will introduce the kernels customized to the “class” as he continues to learn about individual MitM needs from one-on-one discussions in the workplace attending every episode. You are not expected to learn the kernels from reading the website material. The interventionist shows you how to test a kernel in your own social envelope. That’s the only way you get to own the knowledge.

The English pioneers

A review of MitM history will help to understand why intelligent preparation is necessary to stage the FLLP.

Foreman were ignored, demonized, and attacked from the advent of the industrial revolution in 1750 England forward. The history of the foreman role is fragmented, sporadic, and biased – as if foremanship was an obsolete fad. The Establishment, devoured by the compulsion to deskill and subordinate the working class, steadfastly refused to treat the revenue crew as a lived relationship between creatures of flesh and blood. Aristocrats want foremen to be insignificant, harsh, arbitrary, despotic, and interchangeable persons – all the while the role calls for the keystones to be the “tsar of productivity.”

In the USA literature, the phrase “man in the middle” first pops up after the civil war when the industrial revolution shifted into high gear. For over a decade, absentee factory owners gave the foremen free rein to run the mills, so flak from above was seldom a factor. As the number and size of industrial corporations grew, the foremen class was often recognized for its key, critical role in revenue generation and stability. At first, foremen were well rewarded for their role in social system prosperity. Because of the 2½ rule, that role cannot change. In effect, the laws of Nature prevent any other hierarchical functionary to deliver prosperity. Personality and discipline competency have nothing to do with Plan B.

In the 1890s, after Taylorism started spreading, management encouraged education of their front line leaders, MitMs, in the art and science of foremanship. Support by big industry materialized through contributions to the YMCA to set up and operate foreman clubs for training. These clubs were highly successful and noted champions of Taylorism, like Harrington Emerson, traveled from club to club orating at YMCA convocations of foremen. The lead role played by YMCAs in organized foremanship training lasted until after WWI.

When labor unions became major players in industrial expansion, the foreman class was intentionally marginalized. Lawyers on both sides of the management/labor negotiating table excluded foreman – because they were recognized as being on both sides (MitMs) of the table. Let the unbroken history of anti-foremanship aggression by the Establishment be a clue.

In 1938, the CIO established a foreman division for negotiating contracts with management. It lasted a little over a year. Recognizing their critical role in industrial productivity for wartime, the government stepped-in during WWII, as it did in WWI, to educate and reward foremen. Foremen formed unions and negotiated separately with management.

The published, realized effect of foremen unions was an increase in workforce productivity of 25%. Behold. Let the failure of this monster windfall benefit to draw due attention to the critical role of foremanship be a clue about management groupthink.

This brief interlude of collaborative foreman power was so successful for foremen and their organizations, demonstrating the exclusive capability of foremanship to make the company prosperous, the ruling class overruled Truman’s veto of Taft-Hartley in 1947. The organized-foremen run, closed down by Taft-Hartley, is still dead. So much for windfall profits as a head-shed incentive to respect human rights and make money at the same time. Let the Taft-Hartley atrocity committed by the potentate class on MitMs be another clue to the loaded dice.

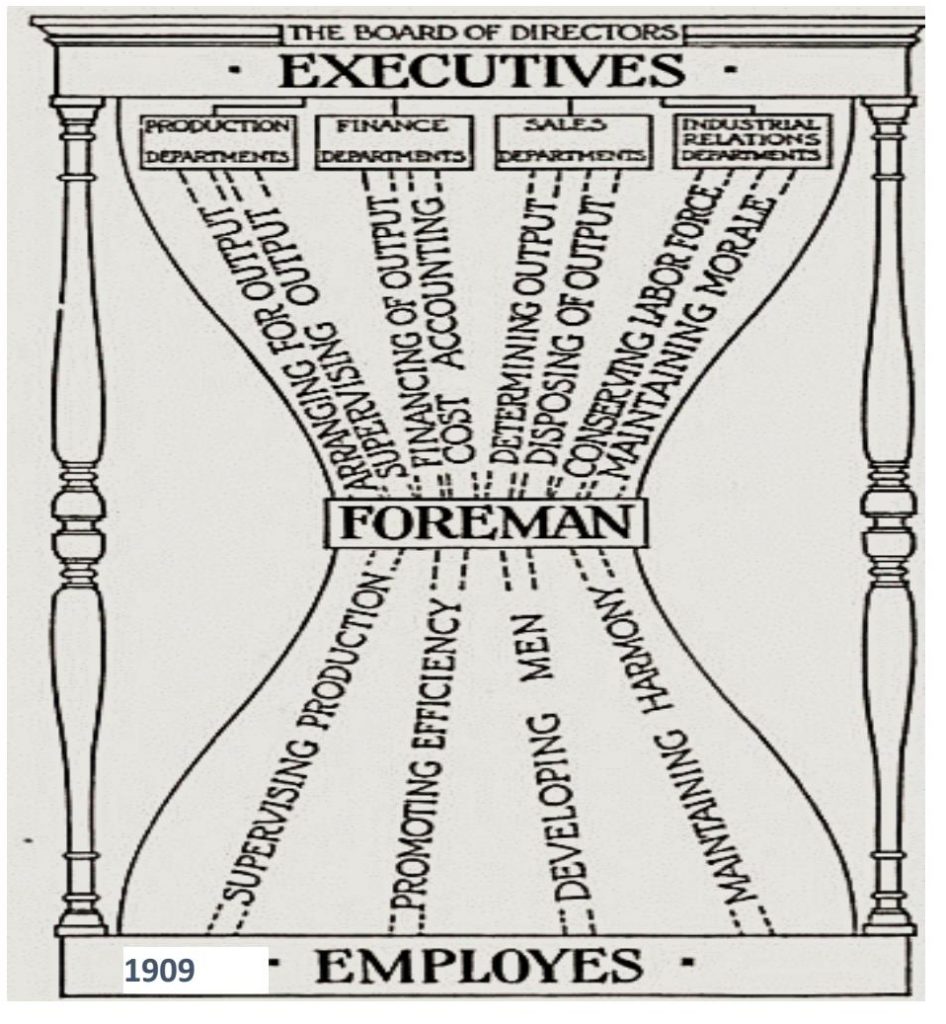

The MitM/foreman role is the center of the “hourglass” between the workforce (implementation) and management (delusion) because a steep hierarchy cannot function any other way. The MitMs represent and connect both “sides” of the unavoidable language divide to each other and neither to themselves. Robbed of their capacity to withstand the strain of the role, MitMs are caged in a societal no-man’s-land designed and policed by the ruling classes.

No level in the hierarchy requires a broader span of knowledge and competency to fulfill the hierarchical role (FF) than the MitM. The 1909 hourglass representation just scratches the surface. Every book and article about foremanship devotes a third of its content just to enumerating the various responsibilities of the MitM. To this day, whatever anyone thinks ought to be done that doesn’t fall squarely in their own narrow slot is tossed over the wall to the foreman. Corporate finance? He should be familiar. Worker relations? He should be an expert.

While one viewpoint calls this ubiquitous practice a cop out, the fact of its necessity defines the MitM role. Of course the head shed and general staff can know nothing of implementation. Of course the laborer knows nothing of high finance. Of course everything has to come together to make the organization viable. Where else can this merging of the two disparate worlds, the FF built into every social system, take place but at the center of the hourglass? A government bureaucracy?

Take a breath:

Realize that the MitM squeezebox driving you bonkers is no accident, no miscarriage of the fates. That it is perforce the goal of the upper classes is aligned with potentate groupthink. You will see that foreman abuse, as seen from the aristocratic level, is the only means they have available to tolerate their cognitive dissonance about authority being disconnected to positive power. The takeaway is: never give the aristocrats the benefit of the doubt.

Realize also that organizational dysfunction always increases with time, often exponentially. Because you see corrective action in other systems, you may think the wreckage and human debris of OD is self-limiting – that when the damage becomes so large it threatens the continuation of the organization itself, the perpetrators will pull back. Destroying the company is not a limiting factor in choosing remedial action. Running the company well is not even in the top ten of motivations. The takeaway is: in Plan A, bad conditions only get worse

Resume thinking

It is the role of the MitM/foreman/keystone to take the abstract, delusional, intangible “stuff” in the top of the hourglass and, positioned at the orifice where it all passes through, turn it into the tangible “stuff” of task actions in the workplace – transmuting straw to gold as it were. The lesson about the social hierarchy to be learned from this transmutation role is that both sides of the hourglass use the MitM as a punching bag. Where you might think the MitM should be appreciated for his essential functionality, the reality is that he is denigrated at every turn. When you accept this fact, you have begun to understand the weird and counterproductive world of organizational dysfunction (OD). Rational and pragmatic it is not.

The foreman/vector/ front line supervisor is the intermediary between capital and labor and embodies the complexity of the labor relationship and the ambiguous (delusional) boundaries of class. The MitM confronts each of their divergent expectations, hopes, fears, representations of self, and assumptions about the square deal – head-on. He is the primus inter pares of the organization. He knows that positive reciprocity, the goal, can only exist when relations of power, not authority, are balanced. He is a study in how the workforce is managed in Plan B. He knows that the “drive” system of discipline and punishment only produces animosity.

The sordid history of MitM creation and abuse is proof positive that the Establishment has always known about the built-in unilateral social power of the foreman role. It has deliberately punished the front-line supervisor, the MitM, the source of its revenue, resenting the fact, never to be admitted, that authority and power are unrelated social phenomena. So, to deal with cognitive dissonance. it employs its opinion-based authority to revile and castigate the foreman until he acquiesces to accept a corrupt, inferior role.

The salutary effect of his act of submission on management ego is short-lived, however, with reality soon calling for booster shots. Every MitM knows the drill. Any MitM can recite the endless organizational inanities and ironies in their work experience, alone or in choir.

Once the foreman accepts his fake inferior status to his superiors delusional “power” as divine will, when management penalizes the foreman for being inferior, there is no pushback of reasoning. In this way, the potentates of steep hierarchies create their human punching bags. This behavior is associated with insecurity and self-image issues that are inherent in their false authority/power assumptions. Authority is powerlessness. Authority never built the equivalent of Plan B prosperity. You can be sure authority never produced Stonehenge or Khufu’s pyramid.

Groupthink instructs that the more authority they exercise, the more power they possess. Believing in their intrinsic infallibility, “why else would they have awarded me unrestricted authority?” Their unavoidable collision with the operational reality produces an endless dose of cognitive dissonance. Even the best autocrats are neurotic.

Taylorism tried valiantly to bypass the foremanship role, spending billions in the attempt, called “functional foremanship.” Rudolf Starkermann first demonstrated that the position of the front-line supervisor is a universal constant set by mathematical physics. Nature, an equal-opportunity tyrant, deaf to persuasion, punishes any and all defiance.

In the 20th century, for another clue, the Establishment went out of its way to disperse and destroy workforce history. The literature showed treatment of the workforce by management to be worse than slavery – tantamount to genocide. All sorts of inhumane conditions of workplace toxicity, hours, and wages were noticed and documented. Even politicians decried the brutal workplace practices that were taking the lives of their constituents. The persistent atrocities led to legislation like Workman’s Comp, which answered some of the abuse by adding the wreckage created to the cost of doing business. It is a Plan A tax we still pay.

Plan A encourages corruption, exploiting the doctrine of deliberate ignorance, as a conspiracy to deceive.

Think of Business as Usual, Plan A, as a bank robbery in process. The crooks need undisturbed time to carry away the loot. As long as the actual transfer can go on undisturbed, the robbery will be successful. What the robbers do not want is to be discovered during the heist. The stakeholders should think of their risk as an ongoing robbery. They should assume corruption. If their safeguard is built on the assumption that the place is crooked, it will monitor ongoing activity to see that it is appropriate to purpose. There is no need for faith and trust. These are hallmarks of your garden variety corrupt corporate governance system. If you avoid the enablers, you do not need to trust.

Digitizing book-collection efforts by Google and others, enabled us to reassemble most of the large library. It’s all in .pdf on a 16G thumb drive you can have for the asking. Anything published after 1925 when the academics took over, with the blessing of the Establishment, misses the point. Not one of our great mentors, such as Chris Argyris, ever knew the early history of OD had been recorded! No university holds a collection more than 5% of the library on the thumb drive.

Views: 216