Keystone: Instrumental Social Power

There are several ways to make the case for the role of the MitM/keystone level in the hierarchy as sole gatekeeper of organizational prosperity. The case made here is on empirical grounds.

Because WW I brought out the truth about management values, going from Plan A before the war to plan B during the war back to Plan A after the war to end all wars, everyone noticed the contrasts. The population assumed because the aristocracy saw what productivity could be achieved with Plan B, the ruling class would embrace it. By 1920 it was apparent that management had gleefully restored pre-war workforce absure with the signing of the armistice.

The instrumental role of the foreman level is established by the ascertainable facts:

- No other level in the hierarchy has the span of responsibility for prosperity

- No other level in the hierarchy has control over workforce activities, by design and assign, that deliver prosperity

The range of responsibilities unique to the foreman says it all. One of the many enumerations was provided in a correspondence course developed by Kennedy for foremen in 1920. The first lesson is provided here. The full course is on the .pdf thumb drive. Although this material was prepared a century ago, it is a glove fit for today’s scene. This method of learning is not hyper-learning. That requires the FLLP.

Duties and responsibilities of the foreman (1920)

“Each corporation answers responsibility matters for itself by the measure of backing and co-operation the management gives the foreman. Recently, when the superintendent of a large industry asked his foremen to put down in writing their own understanding of their duties, it took them over a month to analyze and formulate their jobs. Even a brief survey of any plant will show that the foreman is primarily responsible for the important functions of production maintenance, cost control, and force maintenance.

Yet for years the foreman has held an anomalous position. To the workers, he was the boss. To the boss, he was a worker. In his own mind, he was “the goat” of both. His pay rate was only a few cents higher than that of men he directed; his responsibilities and worries were many times greater. Only the pride of foremanship held him to his thankless task.

When America went to WWI, the demand for output and ever more output fell very heavily upon the foreman’s shoulders. It was up to him to take men who had never seen a ship, and turn out vessel after vessel with them; to take women who had never seen a machine, and turn out finely machined parts with them. In varied industries all over the country, it was the foreman who took new workers, new machines, new processes, and got out production at a speed that amazed the world.

Management at last awoke to a realization of what the foreman meant to production; admitted him an essential factor in management; acknowledged him the key man in industry. On him, as much as on any other official of management, depends the:

- Getting out production

- Holding down of costs

- Gaining the co-operation of the workers

- Interpreting the company policies

No amount of staff assistance from higher executives can or should relieve the foreman of the actual responsibility for synchronizing his men, his machinery, and his materials. It follows that, as the line officer closest to the employees, most immediately in touch with the production, he must be given the opportunity to develop himself to meet this responsibility in full.

We are now entering upon a new industrial era—a period of economic enlightenment for the worker. The man who has so long functioned as a “hand” is beginning to use his head. He is seriously questioning a score of things that heretofore he has been told were none of his business. And the worker is learning fast — but too often from teachers of false and un-American doctrines who are both ignorant of and indifferent about the true facts. To handle successfully this awakening, restless, suspicious spirit in the men under him, the foreman must have a clear understanding of the problems troubling them, and a definite knowledge of the sound principles and methods of industry.

The title of foreman is in itself no longer sufficient to command obedience and respect. The foreman of today must more than ever prove himself worthy and capable of leadership, in thought as well as in deed. Recognition of this importance of foremanship, and this necessity of training foremen in the fundamentals of business and management, is today universal. To the editors and authors of this course, it was apparent years ago.

Good foremen are made, not born. In the past, many a good worker has been spoiled to make an indifferent foreman. Today, many a good foreman is paid less than an indifferent piece-rate operator under him. Such conditions make for industrial unrest, departmental disorganization, and inefficient production.

The foreman is the key man in industry. Upon his training or lack of it depends the success of his department, and — to a very real extent — the success of the whole concern. It is our confident belief that this course, particularly when given the full co-operation of the management, will meet every requirement in training the foreman for ‘Better Foremanship.'”

THE FOREMAN’S PLACE IN INDUSTRY

The foreman of yesterday had only to know the technical phases of production to “get by.” The better foreman of today and every good foreman of tomorrow must know much more than this. He must know the work of course.

But he must also know his men, their characters, abilities, and possibilities. He must also know how to stimulate their ambition, how to promote and reward their initiative, how to improve their workmanship. He must also know how to create social conditions in the community that will permit every man to lead a decent family life and to take an intelligent interest in a decent, democratic, and at the same time efficient government. He must know how to get every man to do a fair day’s work and how to guarantee him a fair day’s wage. He must know how to get every man in the shop to give every other man a square deal and a helping hand. He must understand how to improve conditions, maintain high standards of work and wages, and at the same time reduce prices.

1. Why study foremanship

Why should the foreman study his job and the job ahead? Why should he go outside his job to study his relationship to other plant executives and the industrial world in general? Why should he give up to such study some of the too few hours that he can call his own?

Because the foreman’s job is one of the biggest, most complex, and most important in industry, and is constantly growing in all these respects. Because there is a bigger job ahead, either in increased responsibility with increased remuneration or in definite promotion to a higher executive position. Because nothing is outside his job that affects his work, and every industrial change or advancement eventually comes back to him to be put into effect. Because his direct line of promotion is through his present job, so that making himself more valuable to his employer will automatically increase his value to himself.

2. Necessity for increased production

The cry of the world is for increased production. The World War killed ten million men, destroyed hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of property, laid the fertile fields of Europe desolate, and wrecked many of her most productive communities. For years to come, the world must choose between increased production and starvation.

Increased production means primarily three things:

- Increased intelligence in the development and distribution of raw materials and supplies

- Increased improvement in effective methods of production

- Increased promotion of the earnest spirit of co-operation among workers that makes for greater output and greater harmony

For years the foreman has held an anomalous position. To the workers, he was the boss. To the boss, he was a worker. In his own mind, he was “the goat” of both, a man in the middle. His pay rate was only a few cents higher than that of men he directed; his responsibilities and worries were many times greater. Only the pride of foremanship held him to his thankless task.

These are the future tasks of industrial management. To accomplish them, better work must be exacted of all who hold the reins of management, so that the resources of nature and of men may be best used to feed and clothe and shelter all mankind.

On the factory foreman rests much of the responsibility for this essential increase in production. Foremanship is an essential part of management. This has always been recognized; now we are beginning to realize that the foreman is really the key man in industry. Standing between the planner who works only with his brains and the doer who works only with his hands, we need a third man who can work with both. He must be able to understand and appreciate the ideas of the executive, and translate them into action by instructing and supervising the energy of the worker. He must be able to interpret the needs and problems of each group to the other, and convince them that their mutual interests are best served by serving the public. That man is the foreman. His is the key place in industry.

4. The future of foremanship

The importance of foremanship is daily becoming better recognized. The larger and more progressive companies are taking increasing care in the selection and training of their foremen. The bad custom of haphazard promotion is passing. It used to be that men were appointed foremen simply because they were good workers themselves. Without any special instruction they were suddenly called upon to supervise the work of their recent fellow workers. Mr. Joseph O’Neill, Manager of the Research Department of the Good year Tire and Rubber Company, aptly described this situation in an address before the National Association of Employment Managers:

How do you pick a foreman? Who is he? Perhaps he is some piece worker that has shown by some quality or other, at some time or other, that he is a little better than the fellows around him. All right, you need a foreman. You pick him. Old Dame Fortune picked him out and put him on a pedestal.

“Ah! You are a foreman.” The magic wreath goes round his brow. “You know all about efficiency methods, time study methods.” Magic! “You know all about planning; you are an expert planner. You know all those things. You are on that pedestal now.” On the other side, a little dab here. “You know all about handling men. You are on that pedestal. You are a Foreman.”

“Why,” asked Mr. O’Neill, “should we put a man on that pedestal and that minute expect him to have all the virtues of Job and the wisdom and the knowledge and the foresight of the factory manager?” Today many people are asking this same question, because they realize that this old haphazard method of selection was unfair both to the foreman and to the employer. Many companies have set about remedying this evil by giving increased opportunity for training to the men who are already foremen and those ambitious to become foremen. And the men themselves are awake to their need and are eagerly availing themselves of every opportunity for self-development.

These several facts assure both an increasing recognition of and reward for the work of the foreman and also an increasing expectation of real results from him. Those companies and foremen that today are making possible a better type of foremanship are thereby raising the standards of the position, and so making it imperative for everyone desiring such a position to rise to these standards. In the future, foremanship will unquestionably bring greater reward in money and power, provided always that foremen prove themselves worthy and capable of the greater responsibility being placed upon them.

Responsibility increases with industrial concentration

Through the development of steam, electricity, and machinery, the needs of mankind once supplied by the small shop or the home are now being met more and more by large- scale factories and farms. Undoubtedly such concentrated methods of production are here to stay, so that in the years to come it will be increasingly necessary for men to work together in the manufacture of standardized products on a large scale. Thus foremanship will continue to be the key position in industry and will provide the natural line of promotion from the ranks on up to the higher executive positions. The daily work of a foreman enables him to obtain the self-training and experience that figure so largely in what we usually term executive ability, so that foremanship provides a natural avenue of promotion to higher executive positions. The management of men, which is the special task of the general executive, is also the “regular job” of the foreman.

6. Relation to management and men

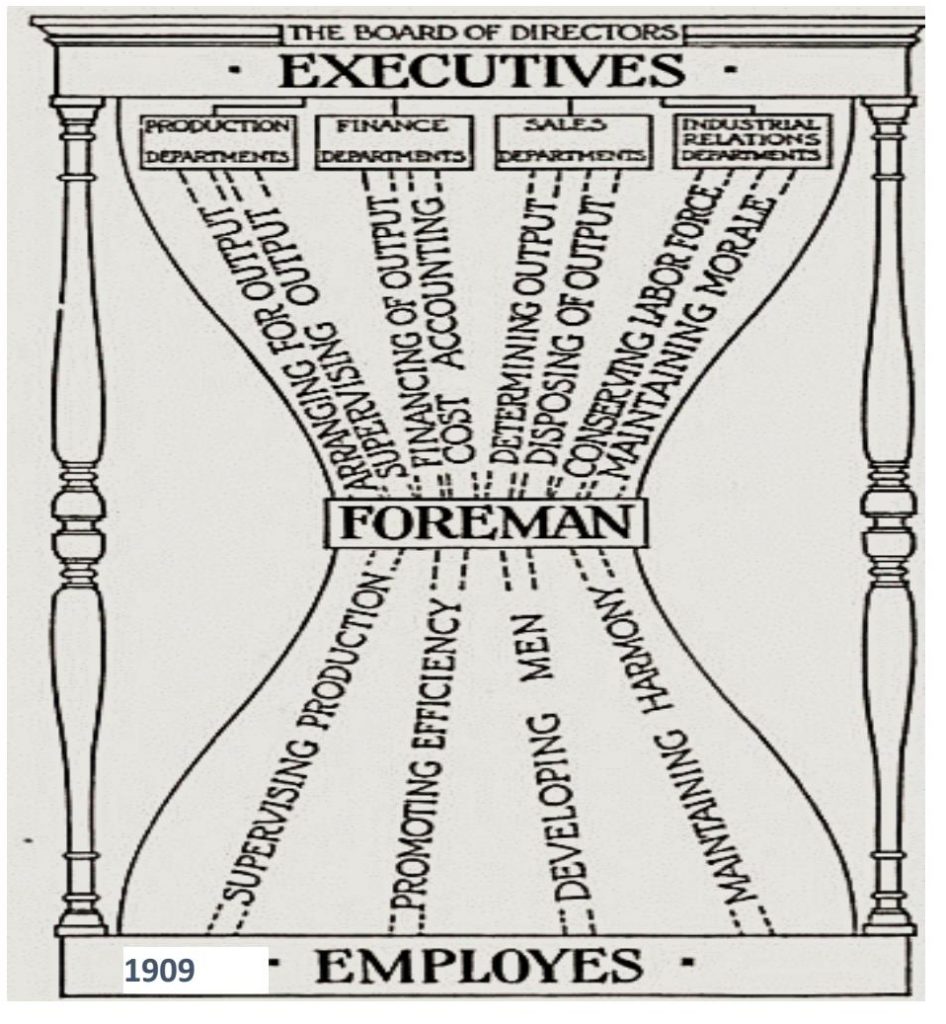

Before we discuss in detail all the foreman’s many duties, let us stand off and look at the whole industrial field in perspective. The foreman is the man responsible for the maintenance of production in his department. This involves his knowing a lot about mechanical processes and a lot about human nature; understanding and working out many things that cannot be set down in rules of instruction or textbooks on methods. In addition, the foreman is the natural interpreter between the management and the men; the instructor, leader, and servant of all engaged in the work of his company. It may help to getting a clear picture of the function of foremanship if we think of the whole problem of industrial organization as an hourglass. The design shown in Fig. 1 is not intended as a functional or organic chart but only as a simple portrayal of the present scheme of management. The words used here differ somewhat from those used in the description of the foreman’s duties that is given later in this lesson; but the ideas are the same.

7. Contact point of industry

This hourglass illustration plainly visualizes the relation of the foreman to the employes and the owners, or their executive representatives, both as the sifting point for the exchange of ideas between them and as the contact point for their joint action. The executive has four main departments at once advising him and carrying out his decisions. The foreman is the man through whom these decisions or orders are transformed into action on the part of the workers.

Turn the glass upside down so that the sands of contact run in the reverse direction. Then the foreman becomes the sifter of the demands, desires, and needs of the workers, and his post becomes the testing ground whereon the individual demonstrates his capacity for leadership. Those who prove they possess this ability are quickly sifted to the other side of the glass as part of the directing group.

It makes no difference whether we consider this relation in the rose-colored glasses of those who dream of a different social organization. The most radical form of industrial government ever suggested recognizes the need for expert management as the directive force in production. Centralized production is here to stay. It has proved conclusively that it is the most economical and efficient way of supplying to the people of the world the things which they need. As long as this is true, there will continue to be groups of men working together in individual plants, whose work must be intelligently directed, instructed, and supervised. The question of ownership plays no part. These are functions of management which will always be essential light of our present-day social organization.

Try it out yourself. You will quickly realize how necessary, as well as how difficult, competent supervision is to a group of workers. Real foremanship calls for the very best that is in a man. In return, it develops the very best that is in a man and makes him increasingly capable of being entrusted with greater responsibilities and power.

8. Essentially overseer of production

The foreman is definitely a part of management. Though he should be, and probably in most instances is, capable of doing any of the jobs in his department, he should not in practice regularly do such work except as it is incidental to training or supervising the workers under him. He is primarily a manager.

Webster defines a manager as “one who directs or conducts anything; a skillful economist.” This latter definition is particularly worth noting for it emphasizes the point that all management has, as its chief purpose, the skilled use of the economic factors that enter into the work for which it is responsible. It is up to the foreman—whom Webster defines as “an overseer”— to see over all the elements of his production problem and to make skilled use of the machinery, materials, men, methods, and motives which he must cause to work together harmoniously for the output of his product.

Three Major Functions of Foremanship and Their Chief Factors

- Developing initiative

- Conserving health, safety, and well-being

- Maintaining discipline

- Securing competent workers

- Promoting team play

- Training workers

- Inspiring loyalty

- Adjusting grievances

- Interpreting policies

THE DUTIES OF FOREMANSHIP

Productivity

12. Procuring tools and materials

The necessity of system in procuring tools and materials is obvious and the following points will be treated later: keeping stores, stock bins, and stock rooms; making and recording of inventories; and methods of requisitioning and recording.

13. Keeping machines repaired

This involves preventing breakdowns by continuous inspection and maintenance; preventing delays by maintenance of adequate reserve supplies in good order for emergencies and replacements; the fixing of responsibility both for the care of and for any accident to machines; and finally, the methods of providing for immediate repair. It also involves a knowledge of the depreciation on each machine and the method by which cost analysis provides for covering the depreciation and replacement charges.

14. Routing work

- Maintenance

- Procuring tools and

- material

- Keeping machines

- repaired

- Routing work

- Regularizing output

- Inspecting quality and

- quantity

- Analyzing jobs

- Standardizing processes

- Cost Control

- Keeping records

- Setting rates

- Conserving waste

- Increasing efficiency

- Reducing overhead

- Hiring make up

- Estimates

15. Regularizing output

Work well planned will thereby be made regular. A steady flow of work into and out of the department is essential to maximum production, minimum cost, and the maintenance of proper industrial good will. This can be attained by the foreman, either on his own initiative or in co-operation with other executives.

16. Inspecting quality and quantity

All kinds of inspection tests have /been devised to make it easy for the foreman to keep up both the quality and the quantity of the goods turned out in his shop. In many instances, the foreman is given special assistants, to act as inspectors for him.

17. Analyzing jobs

Job analysis is a new high-brow name for something everyone has been doing consciously or unconsciously for years. It is now recognized as a prime factor in proper labor specification and planning of work.

18. Standardizing processes

Standardizing processes is another method of good management that is receiving increasing attention. Such things as adopting or inventing machinery and applying newly discovered principles of physics and chemistry are outside the province of the foreman; but he has many opportunities to standardize shop processes and practices.

COST CONTROL

19. Keeping records

Every thing and every person under the supervision of the foreman represents an investment of money by the company and must, therefore, net a return to the company which will be greater than the cost of maintenance. Such costs can be obtained only by keeping adequate records of every phase of the business. The foreman may often curse the clerical work involved in filling out the many forms and reports necessary, but he knows that his records are the basis in fixing prices, estimating on new bids, auditing accounts, and purchasing new supplies. In particular, the foreman is called upon by the superintendent for reports on production; by the engineering department, on the condition of equipment; by the auditor, on overhead charges; by the timekeeping and paymaster’s departments, on output and time; by the safety department, on accidents; by the employment department, on the efficiency, attendance, and capability of employes.

20. Setting rates

The task of setting rates varies with the system of wage payments in use. But wherever piece rates or bonus plans are in effect, it is up to the foreman to help in setting them justly and—which is equally important—in explaining them fully to the workers. The actual setting of rates is generally done by an efficiency man in the engineering department or on the superintendent’s staff, but he must depend on the foreman for help in gathering his facts and in translating them into dollars and cents.

21. Conserving waste

Waste is a characteristic of present American working methods that must be eliminated if we are really going to reduce the high cost of living and maintain our position as the leading productive nation of the world. In shop practice, as in our personal expenses, it is “the little leaks that count.” The foreman and the workers under him can do much to stop unnecessary waste in their daily operations. The efficiency staff or department, where there is one, must depend on the foreman for much of its information and on his co-operation for results.

22. Increasing efficiency

Increasing efficiency is & general task that is handled in a large way by the plant superintendent, engineers, and others of the management, but which in detail must depend largely on the observations and efforts of the foreman.

23. Reducing overhead

With much of the overhead cost the foreman has nothing to do, though he must understand how the figures are obtained. But he can help reduce his overhead by conserving his waste, improving his processes, increasing the efficiency of his force, and keeping the expense of supervision at the practical mini mum. In these matters the foreman acts generally under the direction of his superintendent or department manager.

24. Making estimates

In most concerns the foreman has nothing directly to do with estimating costs on new jobs or new bids. However, he should know what factors of cost, other than production and overhead, enter into such estimates and should figure how they could be reduced.

In a small steel plant in New Jersey the custom is still to call in the foremen whenever the company is asked to bid on a new job. This is a specialty factor and no two orders are the same. The foremen are asked to figure out how little they can get the work through for and are held responsible for carrying out their rates if the order is secured. Even in larger concerns, where the estimates are made outside the production department, the foremen are often consulted on bids for new work. In every case they should be interested in knowing how such estimates are figured and in reducing wherever possible such costs as come under their control.

This entire problem of cost maintenance involves a good deal of the “paper work” that so many foremen bitterly resent. If they are well informed and progressive, however, they will resent only unnecessary record keeping and will endeavor to shortcut the paper work by devising better forms and eliminating nonessentials.

Human problem important

The greatest problem in industry today is the human problem. We have been so much in the habit of thinking of factories as places where raw supplies are turned by machines into useful products that we have nearly forgotten the fact that these supplies and machines are only the tools that men use in their daily work. It is really the men that are all important. In the present effort to put the square deal spirit back into factory relations, the foreman has a very important part because of his constant personal contact with the rank-and-file workers.

26. Securing competent workers

Management has learned to realize that a tremendous waste, both social and financial, results from a continuous stream of men flowing into and out of industries. Right hiring methods offer one way of stopping this labor turnover. The foreman should understand such methods and appreciate their necessity.

27. Training workers

For reasons fully explained later, the present-day worker has never been properly trained in the rudiments of any trade. The American people are beginning to realize that something is radically wrong with our whole educational system, and industry is beginning to see that it is in a large measure responsible for the existing industrial ignorance and the resulting unsatisfactory conditions.

Heretofore industry has allowed the young boy or girl to come directly from the public school or the farm, and pick up in a few weeks enough superficial knowledge to “make out”; today we realize that the untrained worker is a constant drag on industry. He is the disinterested worker, who spoils his tools or materials in cheerful ignorance both of right methods and of the value of his supplies and his time. He is the shiftless worker, ready to change his job at a minute’s notice and willing to slack on his job at any time. He is the troublesome worker, who always carries a chip on his shoulder and grouses at anything and everything.

Industry is finding that it pays to train workers to work more effectively and to appreciate their relationship to production as a whole; and it is utilizing the foreman as one of its chief instructors.

28. Developing initiative

Our American educational system runs us all through the same hopper; it has no time to consider each child as an individual. Will industry continue to make the same mistake? To consider factory workers merely as “hands**—or worse, as numbers—is to stunt their individual ambition and ability. No man wants to be known as a number, even in jail. We all consider ourselves as individuals and want others to consider us as such; we can do much better work if we are permitted a chance to express our own ideas in our work.

The importance of this natural creative instinct in production is now beginning to be realized by employers and by the public. Individual treatment of workers is becoming an essential duty of management and of foremanship. One of the happiest results of such treatment is the development of initiative—the ability to go ahead and do things without being constantly ordered and directed. But initiative alone has little practical value; to produce desirable results it must be harnessed with knowledge. For this reason many foremen, feeling the desire to put more of themselves into their work, are eager to get training that will teach them how this can be properly done.

29. Conserving health, safety, and well-being

We know that it is good business to keep a machine in good running order; to keep every mechanical part well oiled and in constant repair, and to allow it certain periods of rest. And knowing that a machine can last only a certain number of years, we charge against it annually a fixed percentage of its cost to provide for its depreciation and final replacement.

The human body is only a machine—a wonderful mechanism, indeed, more beautiful in the assembling and coordinating of its many intricate parts than any device the mind of man has conceived. But in its use we must exercise great care not to put too heavy, too continuous, or too wearing a strain upon it, lest it break down before its time. Furthermore, if we are to reduce its depreciation to the minimum, and so get the maximum possible service from it, we must regularly spend money on its proper upkeep.

Industry is beginning to appreciate this fact and is now providing for the maintenance of health, safety, and service work purposed to develop and conserve the general personal efficiency of the workers. We used to consider this health and safety work largely “welfare” and sneer at it as “fancy trimmings”; but the excellent results it has accomplished force us to take it seriously. The foreman who neglects any opportunity to promote the well-being of his workers is at once failing in his duty to them and limiting his influence over them.

30. Maintaining discipline

The day of controlling men by swearing, bullying, threats, or superior physical strength is over. “Strong arm” or “mean tongue stuff” always feeds industrial discontent and trouble. If we could trace strikes to their real source, we should find a large percentage growing out of resentment toward foremen who nagged, cursed, threatened, and beat their men. The Great War definitely killed Czarism in the shop and army, and the foreman who holds his job by the violence of his language or the size of his fist will have to step aside.

To get and hold a following today requires leadership based on greater ability, broader vision, and sounder judgment than are possessed by the average. This does not mean mollycoddleism at all. Far from it. What we all seek today, whether we are workers or foremen or executives, is straight man-to-man treatment. We respect the man who can inspire our minds, teach us how to do better work, and satisfy our desire for friendship; we cheerfully accept him as our leader, and gladly follow his lead. To such a man, discipline comes easily and naturally. His men obey him because they want to please him, rather than because he has the power to punish them. He is rather their father than their boss; and if he is worthy of foremanship, he will be proud of this relationship and will do his utmost to deserve and hold their regard.

This whole subject of maintaining discipline is so integral a part of a foreman’s work that our discussion of it runs all through the course. At this point it is chiefly important for the foreman to realize its seriousness and to ask himself what kind of a leader he would prefer to follow. Then let him try to be such a leader to the men working under him. The Golden Rule has proved very practical as a shop rule.

-

Inspiring loyalty

Ten million men were killed in the Great War. Furthermore, for every man who actually laid down his life, there were hundreds who risked the same fate. Why? What power can cause men to grapple with death in such gigantic numbers? Fear and hatred, pride and personal ambition, could never move so many men to such great sacrifices. Is not the true motive loyalty?

To what were these millions of soldiers, these hundreds of millions of civilian workers, loyal? Certainly to their officers, their governments, their leaders. But that loyalty was given only because these men and institutions stood as symbols of the national idea. It was this idea for which millions willingly fought and died. It is always to an idea that men are loyal. Only a tyrant exacts or desires loyalty to himself. All true leaders strive to represent the common ideas and ideals of their people so that the people will be loyal to them as representatives of these ideas.

A foreman can win the loyalty of his workers by proving in words and actions that he is truly representing their ideals and constantly striving to carry out their ideas. To do this the foreman must understand the common purpose of all workers, from the president of the company to the laborers in the yard, and must know and practice the methods that will best advance their common benefit. He may succeed for a while in getting out production by cracking the whip, but he can never inspire loyalty by such means. And with out loyalty he cannot long get out production.

31 a. Dangers of disloyal propaganda

As an indirect result of the Great War, this country is facing a great wave of radical economic theorizing that attempts to destroy our faith in the principles on which our institutions were founded. To many men the normal methods of business, the efficient production of goods, and the just distribution of rewards for effort appear as a bit of hokus- pokus or, what is worse, as a gigantic hypocrisy.

Radical propaganda has been widely used to prove that the workers have no chance to better their condition by strict application to their work and by peaceful presentation of their viewpoint to employers and the general public. Instead, many schemes are proposed that threaten the bases of our political and industrial institutions. The danger of such propaganda is increased by the loss of personal contact between employers and workers and by the great number of foreigners who have never made any attempt to become American citizens or to understand the principles on which this country was founded.

It is necessary to be fully conversant with this propaganda and to understand both the schemes advanced by the propagandists and the social institutions they so glibly attack. We sometimes mistakenly consider such subjects high brow and lacking in direct bearing on our daily work. But every foreman knows that false or muddle-headed ideas in the minds of his workers have a very direct influence on the amount of interest they take in their work and the spirit in which they get out production.

32. What foreman’s job comprises

What is a foreman’s job? Where does he fit in? These questions are puzzling many men who are now acting as foremen or who hope soon to be made foremen. In answer, we know that the average foreman is called upon to:

- Plan his work

- Inspect his machines

- Requisition his materials and labor

- Look over applicants for employment

- Route his work and assign definite jobs to his men

- Train the new employees

- See that everyone has the right materials, tools, and supplies all the time

- Supervise the production

- Inspect the product

- Keep tab on the quantity and quality of output of each worker

- Keep track of each man’s time

- Keep an eye on the ventilation and sanitation of his shop

- Keep the peace between workers and between them and the management

- Help his workers in times of sickness, accident, sorrow, or legal difficulties

- Maintain discipline

- Know the elements of cost

- Reduce costs

- Figure estimates on new jobs

- Regularize the flow of work into and out of his department

- Report on labor turnover, absenteeism, tardiness, and unrest

- Report on output

- Report on breakdowns, repairs, and requests for additional supplies Report on the earnings and capacities of his workers

- Rate his men and make recommendations for promotion, transfer, and discharge

- Help in setting rates and determining bonuses

- Teach the workers how to make themselves better citizens

- Interpret company policies and traditions to workers

41. Summation of duties

This list of duties could undoubtedly be lengthened without exaggeration. Good management must endeavor to shorten it by making the work of the foreman more definite and more nearly within the limits of reason. Of course, many of the duties listed are really different aspects of the same fundamental task, so it might be fairer to summarize the foreman’s duties under these heads:

- Provision of proper tools and materials

- Supervision of production

- Supervision of labor

- Reduction of costs

- Conservation of waste

- Co-ordination of work

- Training and maintenance of a loyal efficient force

Except in the smallest plants, no single foreman could do all that this summarized list of functions implies unless he had expert help. While differences in method make it impossible to show exactly how our American industries bring such expert help to the assistance of the foreman, we can at least chart the major functions in which the foreman needs such help. The foreman’s major functions:

- Production maintenance

- Cost control

- Force maintenance

Under these functions are listed the chief factors composing them. For each of these lesser functions modern shop practice has developed either automatic checks or guides or specially trained experts that greatly lessen the foreman’s work.

19. Foreman has a real job

War is a better stage manager than peace. The need for production stands out more vividly against the background of bloody battlefields than against the equally somber but less dramatic picture of poverty, under-nourishment, and bankruptcy. But these conditions actually exist in the world today, and will continue to exist until all the people of the earth have been helped to rehabilitate themselves and to recover the wealth and energies destroyed by war. It is very largely up to the foreman to bring home to the worker this sense of production necessity and the idea of group interest to which he can be loyal.

The workers of this country have been misled by reckless agitators, who have poisoned their minds with the belief that they are not working for the benefit of the world, but only that their boss may become richer; and that their own best interests will be served by lessening rather than by increasing their output. No greater lie was ever uttered; yet this absurd statement has done much harm. The efficiency of labor a whole has dropped far below normal, although many offer startling proof that labor has never reached the efficiency of which it is capable. The economic conditions we are facing, both in this country and in competition with foreign countries, make it all important that labor should reach its maximum of efficiency.

The foreman must help give the workers a clear understanding of their true interest in co-operative production. He must help build up anew the idea of common interest in production as a service to the public to which all workers can be loyal. In the narrower sense, he must develop the spirit of loyalty to his particular company; but only in such a manner that it will arouse a broader spirit of loyalty to our national ideals and the fundamental principles of American economic life.

32. Promoting team play

In every game and business, team play wins. Team play grows out of mutual confidence and a realization that all members of the team are loyal to a common ideal. After the foreman has inspired loyalty, he must impress upon each individual worker the commonness of his purpose with that of all his fellow workers. There is no more valuable asset in a department than this group spirit; and the foreman has no more important task than this of getting his men to work together with real group spirit.

33. Adjusting grievances

Dam up a flowing stream without an outlet, and some day you will have a flood. Let a man nurse a grievance, without the chance of airing his kicks to somebody “higher up,** and some day you will have real trouble. In the rush and hurry of the modern factory there are many opportunities for a man to take offense or to believe an injustice has been done him. It makes little difference whether his grievance is real or imaginary. The important thing is that he believes himself hurt and wants to tell his troubles to someone who will understand.

The exact method used in adjusting grievances depends primarily on the labor policies of the management; but the foreman should not allow this matter to slip entirely out of his control. He should know what complaints his men have to make and encourage them to register their kicks with him. Sometimes just “letting them get it off their chests” will satisfy them. Often a bit of jolly or a hearty encouraging slap on the shoulder will end the matter; but when there is real merit in the complaint, the foreman must bend all his efforts to set wrong things right and keep them from going wrong again.

34. Interpreting policies

The foreman stands immediately over the workers in his department. In line of authority he stands below the superintendent and department managers, who in turn stand below the works manager or president, who is responsible to the board of directors of the company. This board of directors determines the company policy in a given matter, and the executives carry it out through their subordinates. In practice, this means that the executives transmit the policy to the foreman as orders and hold him responsible for its being carried out. Whenever a general company policy involves working conditions or working relations, the foreman will find that he must translate to his men both the policy itself and the orders putting it into effect. Otherwise, the policy becomes a mere scrap of paper. On the other hand, the directors and executives must depend very largely on the foremen for their knowledge of conditions in the shops and the ideas of the men.

Thus the foreman becomes the interpreter to the men of the company’s policies, and to the company of the needs of the men. He cannot shirk this responsibility if he will, for it is part and parcel of his position in the company. The good foreman will welcome this responsibility as an opportunity to further the best interests of the company as a whole. He realizes that he is really interpreting between those two great factors of industry which we glibly call capital and labor and regards it as a rare chance to help eliminate industrial strife and bitterness. The foreman who willingly acts as an honest interpreter between workers and owners is serving not only himself and his company but also his country and his fellow men.

35. Aim of course

Increased production is the crying need of the world today. Those countries that escaped the devastation of the Great War must produce the necessaries of life in larger quantities than ever and with the greatest possible efficiency. America is the greatest productive country of the world. If we want to hold that position, we must turn out more goods at the lowest possible cost that will permit our maintaining the highest standard of living.

This necessitates better management. Especially, it necessitates better foremanship, because the foreman is the key man in industry today and an all-important factor of management. No man today can be a bad foreman and retain his position; but it is also true that no good foreman can properly hope for promotion unless he trains himself to be a better foreman.

This course aims to help foremen train themselves to be worthy of greater recognition and reward, so that they will be ready when the opportunity for advancement comes to them. It is planned as a practical guide to the foreman’s daily routine, a practical reference library of information showing the solution of his daily problems. It gives him a clear explanation of the fundamentals of economics and business organization; provides the best and most practical information bearing on his position as a supervisor of production and a leader of men; and describes not only the methods used but also the goal attainable by the right use of right methods.

Human problem paramount

The greatest problem in industry today is the human problem. We have been so much in the habit of thinking of factories as places where raw supplies are turned by machines into useful products that we have nearly forgotten the fact that these supplies and machines are only the tools that men use in their daily work. It is really the men that are all important. In the present effort to put the square deal spirit back into factory relations, the foreman has a very important part because of his constant personal contact with the rank-and-file workers.

26. Securing competent workers

Management has learned to realize that a tremendous waste, both social and financial, results from a continuous stream of men flowing into and out of industries. Right hiring methods offer one way of stopping this labor turnover. The foreman should understand such methods and appreciate their necessity.

27. Training workers

For reasons fully explained later, the present-day worker has never been properly trained in the rudiments of any trade. The American people are beginning to realize that something is radically wrong with our whole educational system, and industry is beginning to see that it is in a large measure responsible for the existing industrial ignorance and the resulting unsatisfactory conditions.

Heretofore industry has allowed the young boy or girl to come directly from the public school or the farm, and pick up in a few weeks enough superficial knowledge to “make out”; today we realize that the untrained worker is a constant drag on industry. He is the disinterested worker, who spoils his tools or materials in cheerful ignorance both of right methods and of the value of his supplies and his time. He is the shiftless worker, ready to change his job at a minute’s notice and willing to slack on his job at any time. He is the troublesome worker, who always carries a chip on his shoulder and grouses at anything and everything.

Industry is finding that it pays to train workers to work more effectively and to appreciate their relationship to production as a whole; and it is utilizing the foreman as one of its chief instructors.

28. Developing initiative

Our American educational system runs us all through the same hopper; it has no time to consider each child as an individual. Will industry continue to make the same mistake? To consider factory workers merely as “hands**—or worse, as numbers—is to stunt their individual ambition and ability. No man wants to be known as a number, even in jail. We all consider ourselves as individuals and want others to consider us as such; we can do much better work if we are permitted a chance to express our own ideas in our work.

The importance of this natural creative instinct in production is now beginning to be realized by employers and by the public. Individual treatment of workers is becoming an essential duty of management and of foremanship. One of the happiest results of such treatment is the development of initiative—the ability to go ahead and do things without being constantly ordered and directed. But initiative alone has little practical value; to produce desirable results it must be harnessed with knowledge. For this reason many foremen, feeling the desire to put more of themselves into their work, are eager to get training that will teach them how this can be properly done.

29. Conserving health, safety, and well-being

We know that it is good business to keep a machine in good running order; to keep every mechanical part well oiled and in constant repair, and to allow it certain periods of rest. And knowing that a machine can last only a certain number of years, we charge against it annually a fixed percentage of its cost to provide for its depreciation and final replacement.

The human body is only a machine—a wonderful mechanism, indeed, more beautiful in the assembling and coordinating of its many intricate parts than any device the mind of man has conceived. But in its use we must exercise great care not to put too heavy, too continuous, or too wearing a strain upon it, lest it break down before its time. Furthermore, if we are to reduce its depreciation to the minimum, and so get the maximum possible service from it, we must regularly spend money on its proper upkeep.

Industry is beginning to appreciate this fact and is now providing for the maintenance of health, safety, and service work purposed to develop and conserve the general personal efficiency of the workers. We used to consider this health and safety work largely “welfare” and sneer at it as “fancy trimmings”; but the excellent results it has accomplished force us to take it seriously. The foreman who neglects any opportunity to promote the well-being of his workers is at once failing in his duty to them and limiting his influence over them.

30. Maintaining discipline

The day of controlling men by swearing, bullying, threats, or superior physical strength is over. “Strong arm” or “mean tongue stuff” always feeds industrial discontent and trouble. If we could trace strikes to their real source, we should find a large percentage growing out of resentment toward foremen who nagged, cursed, threatened, and beat their men. The Great War definitely killed Czarism in the shop and army, and the foreman who holds his job by the violence of his language or the size of his fist will have to step aside.

To get and hold a following today requires leadership based on greater ability, broader vision, and sounder judgment than are possessed by the average. This does not mean mollycoddleism at all. Far from it. What we all seek today, whether we are workers or foremen or executives, is straight man-to-man treatment. We respect the man who can inspire our minds, teach us how to do better work, and satisfy our desire for friendship; we cheerfully accept him as our leader, and gladly follow his lead. To such a man, discipline comes easily and naturally. His men obey him because they want to please him, rather than because he has the power to punish them. He is rather their father than their boss; and if he is worthy of foremanship, he will be proud of this relationship and will do his utmost to deserve and hold their regard.

This whole subject of maintaining discipline is so integral a part of a foreman’s work that our discussion of it runs all through the course. At this point it is chiefly important for the foreman to realize its seriousness and to ask himself what kind of a leader he would prefer to follow. Then let him try to be such a leader to the men working under him. The Golden Rule has proved very practical as a shop rule.

31. Inspiring loyalty

Ten million men were killed in the Great War. Furthermore, for every man who actually laid down his life, there were hundreds who risked the same fate. Why? What power can cause men to grapple with death in such gigantic numbers? Fear and hatred, pride and personal ambition, could never move so many men to such great sacrifices. Is not the true motive loyalty?

To what were these millions of soldiers, these hundreds of millions of civilian workers, loyal? Certainly to their officers, their governments, their leaders. But that loyalty was given only because these men and institutions stood as symbols of the national idea. It was this idea for which millions willingly fought and died. It is always to an idea that men are loyal. Only a tyrant exacts or desires loyalty to himself. All true leaders strive to represent the common ideas and ideals of their people so that the people will be loyal to them as representatives of these ideas.

A foreman can win the loyalty of his workers by proving in words and actions that he is truly representing their ideals and constantly striving to carry out their ideas. To do this the foreman must understand the common purpose of all workers, from the president of the company to the laborers in the yard, and must know and practice the methods that will best advance their common benefit. He may succeed for a while in getting out production by cracking the whip, but he can never inspire loyalty by such means. And with out loyalty he cannot long get out production.

32. Wartime lessons in loyalty

The Emergency Fleet Corporation of the United States Shipping Board realized this when it engaged the best orators in the country to make inspiring speeches to the men in the shipyards. Through these speakers the keynote message of patriotism was carried to managers, foremen, and workers until every man in the yard felt that on him depended the success of the war against Germany. As a consequence, production jumped. Our brand new American shipyards, with their hundreds of thousands of employes.

War is a better stage manager than peace. The need for production stands out more vividly against the background of bloody battlefields than against the equally somber but less dramatic picture of poverty, under-nourishment, and bankruptcy. But these conditions actually exist in the world today, and will continue to exist until all the people of the earth have been helped to rehabilitate themselves and to recover the wealth and energies destroyed by war. It is very largely up to the foreman to bring home to the worker this sense of production necessity and the idea of group interest to which he can be loyal.

36. Scope of course

This course might be characterized as a “high-school course for foremen”—that is, it completes the “grade- school” education you received as a rank-and-file worker and begins the “college education” necessary for an executive position.

The condensed outline of subjects on the following page gives a general idea of the ground covered.

The workers of this country have been misled by reckless agitators, who have poisoned their minds with the belief that they are not working for the benefit of the world, but only that their boss may become richer; and that their own best interests will be served by lessening rather than by increasing their output. No greater lie was ever uttered; yet this absurd statement has done much harm. The efficiency of labor a whole has dropped far below normal, although many offer startling proof that labor has never reached the efficiency of which it is capable. The economic conditions we are facing, both in this country and in competition with foreign countries, make it all important that labor should reach its maximum of efficiency.

The foreman must help give the workers a clear understanding of their true interest in co-operative production. He must help build up anew the idea of common interest in production as a service to the public to which all workers can be loyal. In the narrower sense, he must develop the spirit of loyalty to his particular company; but only in such a manner that it will arouse a broader spirit of loyalty to our national ideals and the fundamental principles of American economic life.

32. Promoting team play

In every game and business, team play wins. Team play grows out of mutual confidence and a realization that all members of the team are loyal to a common ideal. After the foreman has inspired loyalty, he must impress upon each individual worker the commonness of his purpose with that of all his fellow workers. There is no more valuable asset in a department than this group spirit; and the foreman has no more important task than this of getting his men to work together with real group spirit.

33. Adjusting grievances

Dam up a flowing stream without an outlet, and some day you will have a flood. Let a man nurse a grievance, without the chance of airing his kicks to somebody “higher up, and some day you will have real trouble. In the rush and hurry of the modern factory there are many opportunities for a man to take offense or to believe an injustice has been done him. It makes little difference whether his grievance is real or imaginary. The important thing is that he believes himself hurt and wants to tell his troubles to someone who will understand.

The exact method used in adjusting grievances depends primarily on the labor policies of the management; but the foreman should not allow this matter to slip entirely out of his control. He should know what complaints his men have to make and encourage them to register their kicks with him. Sometimes just “letting them get it off their chests” will satisfy them. Often a bit of jolly or a hearty encouraging slap on the shoulder will end the matter; but when there is real merit in the complaint, the foreman must bend all his efforts to set wrong things right and keep them from going wrong again

34. Interpreting policies

The foreman stands immediately over the workers in his department. In line of authority he stands below the superintendent and department managers, who in turn stand below the works manager or president, who is responsible to the board of directors of the company. This board of directors determines the company policy in a given matter, and the executives carry it out through their subordinates. In practice, this means that the executives transmit the policy to the foreman as orders and hold him responsible for its being carried out. Whenever a general company policy involves working conditions or working relations, the foreman will find that he must translate to his men both the policy itself and the orders putting it into effect. Otherwise, the policy becomes a mere scrap of paper. On the other hand, the directors and executives must depend very largely on the foremen for their knowledge of conditions in the shops and the ideas of the men.

Thus the foreman becomes the interpreter to the men of the company’s policies, and to the company of the needs of the men. He cannot shirk this responsibility if he will, for it is part and parcel of his position in the company. The good foreman will welcome this responsibility as an opportunity to further the best interests of the company as a whole. He realizes that he is really interpreting between those two great factors of industry which we glibly call capital and labor and regards it as a rare chance to help eliminate industrial strife and bitterness. The foreman who willingly acts as an honest interpreter between workers and owners is serving not only himself and his company but also his country and his fellow men.

35. Aim of course

Increased production is the crying need of the world today. Those countries that escaped the devastation of the Great War must produce the necessaries of life in larger quantities than ever and with the greatest possible efficiency. America is the greatest productive country of the world. If we want to hold that position, we must turn out more goods at the lowest possible cost that will permit our maintaining the highest standard of living.

This necessitates better management. Especially, it necessitates better foremanship, because the foreman is the key man in industry today and an all-important factor of management. No man today can be a bad foreman and retain his position; but it is also true that no good foreman can properly hope for promotion unless he trains himself to be a better foreman.

The condensed outline of subjects on the following page gives a general idea of the ground covered.

The Keystone Man in Industry

- The Planning of Work

- The Supervision of Work

- The Objects of Production

- Factors of Business

- Finance

- Markets

- Sales

- Engineering

- Organization

- Industrial Relations

- Securing Competent Force

- Training Competent Force

- Maintaining Competent Force

- Working Conditions

- Hours and Wages

- Indirect Compensation

- Working Relations

- Working with Men

- Foreigners

- The Daily Routine

- Getting It Across

- The Wizardry of Industry

- Measuring-Sticks in Industry

- Industry as a Community Unit

- The Future of Industry

- The Better Foreman

- Factors of a Plant Survey

- Factors of a Sound Industrial Program Future and Opportunities

- Bibliography of Practical Handbooks

38. Learn from others

Often the statements and illustrations contained in these lessons will not apply exactly to your particular problems; but if you will study them a bit, bringing your own experience to bear, you will find that they do bring out certain general principles that can be adapted to your problems. One of the purposes of this course is to encourage you in the habit of reasoning from the general to the particular and so to show you how often and easily you can profitably use the experience of others. It always pays to study other men’s work and thoughts. If other foremen of your acquaintance are taking this course, it will be mutually profitable for you to get together once a week to discuss the lesson. Such discussions will invariably help to clarify your own ideas, besides broadening your viewpoint by showing you how others look at the things that interest you.

39. Read with open mind

It is probable that these lessons will contain certain statements with which you will not agree. But don’t throw the book down in disgust. Argue the matter out with yourself and others until you know why the book is right or wherein it is wrong. You may be sure that no statement will be made without due consideration; but many matters affecting foremanship are still open to honest argument. And it is a fact that we learn more from people with whom we do not agree than from those whose opinion is the same as ours.

Don’t allow yourself to be prejudiced or opinionated. Study your own experiences; match them with those of others; weigh them in the scales of fundamental principles and common sense. Only by such means can you gain a mastery of your own problems and a broad outlook on your own work.

40. Man in the larger sense

For convenience in writing and reading, we shall speak only of the “foreman” and the “workmen.” There is no intention, however, to overlook the fact that the number of “foreladies” and “women workers” is steadily increasing. Women are gaining a great foothold in industry and are proving their right to take up the task of production shoulder to shoulder with men. Women are proving themselves capable not only of serving at the bench and table but also of carrying on the responsibilities of foremanship. But as the same methods and relationships hold true in factory life regardless of sex, it has not seemed necessary to use the awkward “he or she,” “him or her.” The reader will understand, therefore, that this course is written for the overseers of production, whether they happen to be men or women; and that our apparent disregard of woman’s important place in industry is due entirely to the limitations of the English language.

41. Three-position idea

You are doubtless familiar with the three-position idea of promotion—that the man who is ambitious for advancement has a three-fold duty to perform: first, he must give complete satisfaction in his present position; second, he must be training another man to take his place; and third, he must be training himself for the position ahead of his present one. Failure to make the most of his opportunities in any one of these three respects proves him unfit for greater responsibilities; and such failures explain why men with long and apparently satisfactory records are often disappointed that they do not get ahead more rapidly.

More than any other class of workers, the foreman is so situated as to take full advantage of this logical and increasingly popular idea. To be a good foreman in the present- day understanding of the term, he must constantly be training his men in the fundamentals of foremanship and training himself for a higher executive position. This course is based upon the three-position idea. Your mastery of the succeeding lessons, supplementing your practical experience as a leader of men, will enable you to qualify as a better foreman in the broadest meaning of the term.

Lesson 1: THE KEY MAN IN INDUSTRY

The Foreman’s Place in Industry

- Foremanship an essential part of management

- The future of foremanship

- Responsibility increases with industrial concentration

The Post of Foremanship

- The interpreter between directorate and workers

- The responsible overseer of production

- The responsible leader of his men

The Duties of Foremanship

- Production maintenance — factors and methods

- Cost control — use of cost records

- Force maintenance — securing and conserving competent workers

Purpose and Methods of This Course

- A high-school course for foremen

- Reading lessons quiz questions, examination

- The three-position idea of advancement

Lesson 2: THE PLANNING OF WORK

- The Necessity of Planning

- Three functions of foremanship

- Practical dreamers

- Planning is progressive

- Planning as a Process in Industry

- Elements of planning

- General executive’s part in planning

- Superintendent’s part in planning

- The foreman and planning — amount of knowledge necessary — planning meets schedules

- Routing of Work

- Construction of buildings — types in use

- Development of progression of process — types of progression in use Mechanical routing devices — conveyors, belts, trucks, etc.

- Continuous record keeping — permanent inventory

- Routing boards and schedules

Job Analysis

- As an aid in effective hiring

- As an aid in effective training

- As an aid in simplification of operations

- How to make a job analysis

- Job analysis forms

Forms Helpful to Foreman

- Reason for records

- Daily flow sheet

- Comparative production report

- Graphic Presentation of Facts

- Block method of comparison

- Use of symbols

- Graphic curve

- Practical value of graphs

Lesson 3: THE SUPERVISION OF WORK

- Organizing Task of Supervision

- Production depends on supervision

- Quality of goods depends on supervision

- Speed of work depends on supervision

- Functionalizing foreman’s task

- Department organization — assigning work to assistants — human values indispensable

- Requisition and Maintenance of Supplies

- Factory storeroom

- Requisition in advance

- Department stock keeping

- Use of improved equipment

Assigning Tasks

- Sizing up workers’ ability

- Specialization of work

- Relating task to general operations

Keeping Tabs on Production

- Finding out reasons for let-down

- Physical conditions important

- Relation of wages to production — scientific method of determining wages — explaining wage system

- Inspection

- Comparison of different methods — not spying but helpful supervision — self-inspection

- Necessity of co-operation — problems of general management — development of pride in work

Lesson 4: THE OBJECTS OF PRODUCTION

- Industry Primarily for Use

- The knitting of the world

- The world demand for improved and standard articles

- Demand fed as well as met by centralized production

Necessity for Systematized Centralized Effort

- In production — to increase volume and reduce costs

- In management — to maintain effective labor force, eliminate waste (labor turnover, strikes, etc.), and promote co-operative zeal

- In finance — to maintain stable credit and sound value basis

- In politics — to further public “efficiency” that remains democratic—to develop a more conscious American citizenship

- In community action — to provide adequately for social needs of all — to develop common rather than class interests

Industrial Leaders Must Lead

- Within the plant as good managers

- Outside the plant as good citizens

- Foremen are part of the management and must be industrial leaders in all these directions

The Rise of Factory Methods

- Effect on the work — quantity, production, etc.

- Effect on the workers — specialization, monotony, etc.

- Effect on industry — concentration of management, etc.

- Effect on social life — concentration of city living, etc.

- Effect on industrial relationship — loss of unity of interest

Lesson 5: FACTORS OF BUSINESS—FINANCE

Finance

- Arrangement of credits — the foundation of modern enterprise

- Cost accounting

- Explanation of overhead — plant, sales, administration

- Recording overhead

- Indirect and direct production charges

- Budget making

- Necessity for

- Methods of

- Maintenance of stable credit in banks

- Cash account, statements, loans, investments

- The work of capital

- What it is, how secured, how retained, how paid for

- Necessity for interest, depreciation and sinking funds

- What they are, how secured, how accounted for

Relation of Finance to Industrial Relations

- Making production possible

- The division of earnings

- Meeting fixed charges, insurance for futures, and profits

Foreman ship and Finance

- Interpreting policies to workers

- Assisting in sound financing through good management in their own shops

Lesson 6: FACTORS OF BUSINESS—MARKETS

Purchase

- The constant study of supply markets’

- The search for new supply sources and better equipment

- Buying wholesale and storing

- Keeping pace with estimates

Transportation

- Facilities between plants and markets

- Facilities between yards and transportation lines

- Facilities within plant

- Freight rates and differentials

- Methods of packing and shipping

Interdependence of Markets

- Uncertainty of supplies

- Crop failures, strikes, etc.

- Change in styles or consumers tastes

- The Effect on Industrial Relations and Foremanship

Lesson 7: FACTORS OF BUSINESS—SALES

- Estimating Consumption

- Study of markets, styles, etc.

- Judging plant capacity

- Effect of competition

- Stimulating Demand

- Advertising

- Sales promotion

Improvement in Product

- Making product more attractive

- Adapting product to new demands

- Reaching new territories

Sales Policy

- Sales schools

- Necessity of training in factory methods and output

- Necessity of reporting back to factory opinion of purchasers

- The Effect on Foremanship

Lesson 8: FACTORS OF BUSINESS—ENGINEERING

- Plant and Equipment

- Intensive study of production needs

- Location of plant

- Erection of plant

- Arrangement for power, light, heat, etc.

- Arrangement for work progression

- The necessity of large capital layout before any return

- Provision for plant expansion

Installation and Maintenance

- Machine equipment and repair

- Depreciation of equipment — foreman’s responsibility for

- Continuity of power and ventilation

- Adequate facilities for storage and stock

- Standards of sanitation, lighting, heating, etc.

Safety

- Provision of Mechanical Safeguards

- Standards for drawing off poisonous fumes, dust, etc.

- Standards of protection for gears, belts, mills, etc.

- Standards for safeguarding electrical connections, etc.

- Standards for guaranteeing proper water and sewer connections Standards for controlling power and machine operation in time of accident

Improving Methods and Processes

- Routing work as part of installation and maintenance

- Devising and adapting new machines

- Studying and revising operations

- The Effect on Foremanship

Lesson 9: FACTORS OF BUSINESS – ORGANIZATION

- Types

- Straight line Functional

- Line and staff Administrative

Executive Leadership Always Necessary for:

- Group activity

- Direction of others

- Delegation of authority

- Administering responsibility

- Assumption of risk

- Development of initiative

- Standards

- Line of authority must be clear

- Must make quick and responsible action possible

- Must bring to bear on each problem all the knowledge of the entire group Overhead supervision reduced to minimum

Methods

- Various forms of organization — charts

- Relation and interdependence of executives and operatives

The Function of Management

- Neither capital nor labor, but responsible to both

- The controlling factor of economic conditions and relations

- The guidance of production and distribution.

- The co-ordinator of lines of effort into harmonious progress

- The keeper of the keys and of the faith

- The Effect on Foremanship

Lesson 10: FACTORS OF BUSINESS—INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS

The Development of This Newly Recognized Function

- In the country

- In the shop

- Its Constituent Factors

- Correlation under employment, safety, health and service

- The Necessity of Co-ordination of Such Effort

- Responsibility direct to management

- Responsibility direct to workers

The Objectives of Such Work

- Not paternalism

- Not to hold men down

- Not charity

- Education for greater productivity

- Protection for greater efficiency

- Assistance for greater loyalty

- Good will as an economic asset

The Necessity for a Labor Program

- Must be comprehensive

- Must be economically sound

- Must be practical

- Must meet genuine need

- Must arouse genuine co-operation

- Must be judged by results

- The Effect on the Foreman, and His Part Therein

SECURING COMPETENT FORCE

- Centralizing Employment

- Reasons for Labor turnover

Recruiting

- Stealing labor — continual jockeying of rates — false inducements Advertising and scouting

- Private and public agencies

- Necessity of protecting community

- Value of community co-operation and agreement

- Advantages of transfer system

Hiring

- Methods in use

- Trained interviewing

- Trade and psychological tests

- Physical examination

- Limited tryout

- References — society memberships

Forms and Reports

- Necessity for simplicity

- Methods of requisitioning by and acceptance by foremen Filing and cross filing

TRAINING COMPETENT FORCE

- The Need for Training

- Breakdown of the apprentice system

- Danger as well as value of the specialized work

- The Kinds of Training

- Apprenticeship

- Craftsmanship

- Vocational education

- Elementary education

- Social education

Methods of Training

- Vestibule schools

- Continuation schools

- Night schools

- Instruction on the job

- Flying squadron

Objects of Training

- Opportunity for self development in efficiency

- Testing ground for those with latent capacities

- Melting pot of ideas

- School of Americanism

- Arousing creative instinct

- Stimulating ambition

MAINTAINING GOOD WORKING CONDITIONS

- Providing Good Working Conditions

- Light, heat, sanitation

- Lavatory and locker facilities

- Protection

- Providing Attractive Service Features

- Assistance in home finding — dormitories, etc. Lunchrooms — co-operative stores, etc. Transportation facilities

- Recreation facilities

- Providing Proper Tools and a Steady Supply of Work Methods of Administering Standards of Such Features

- Interrelationship with Foremen

Wages

- Relation of wages and earnings

- Relation of wages and company expenditure — labor cost

- Relation of wages and company income

Methods of Computing Wages

- Day work — piece work — bonus and premiums

- Learners’ rates

- Advance by merit, service, etc.

- Basic standard — cost of living — price of unit output — all that the traffic will bear — competitive market rates

MAINTAINING COMPETENT FORCE

Indirect Compensation

Social Insurance — Methods and Types

- Old age

- Sickness and accident

- Life

- Unemployment

Profit Sharing

- Types in use

- Economic fallacies of generalities

Mutual Benefit Associations

Types:

- Objective — insurance, housing, co-operative buying, etc.— athletics, fellowship, thrift, etc.

- Interdependence of Factory, Community, and State Regulations

- Interrelationship with Foremen

WORKING RELATIONS

- Types of Organization

- Individual bargaining

- Collective bargaining — shop committees, union agreement

Standards for Determining Choice

- The search for democratic co-operative management

- The necessity of determining real needs and desires of men

- The danger of control “by might”

- The gradual development of a fundamental policy

Industrial Organization

- American co-operation, sovietism, socialism

- Sketch of history, purposes, and methods

- Necessity of separating the wheat from the chaff

- Necessity of fighting out economic fallacies, and getting back to essential of sound, sane principles of production

- The Necessity Always of Good Management

- Production on large scale here to stay

- Executive direction always, therefore, essential

- The Relation of World Movements to Production

- Interrelationship with Foremen

Executive Leadership

Dependent upon:

- Knowledge of human nature

- Ability to win and hold confidence of others

- Ability to direct and judge the work of others

- Common sense, common decency, common squareness, common modesty

Developed by

- Self knowledge and training

- Mixing with all sorts and conditions of men

- Self respect and respect for others — rights and duties of all

Studying Men

- Each an individual

- Effect of early environment and training

- Effect of habit on character

- Methods of grouping characteristics — helpful but not scientific

Handling Men

- Qualities needed — patience, self control, etc.

- Willingness to learn as well as teach

- Tact, courtesy and judgment, etc.

Development of Individual Capacities

- Often latent — methods of discovery and of fostering

- Objectives — “creative instinct,” ambition, etc.

WORKING WITH FOREIGNERS

- The Immigrant a Special Problem

- Handicapped by ignorance of language and custom

- Naturally distrustful of any but their own people

- Immigrant’s outlook on America — purpose in coming — general experience

- Immigrants in America

- Flow of immigration

- National and racial characteristics

Americanization

- Its necessity

- Its objectives

- Methods in use

- The Foreman’s Duty and Privilege

WORKING WITH MEN—THE DAILY ROUTINE

- Introducing New Workers

- Meeting men

- Acquainting them with work and force

Encouraging Workers

- Suggestions — systems in use