Plan A Background

The history of organizational dysfunction is prodigious. The history of highly-effective organizations is sparse, fragmentary, and obscure. The very popular book “In Search of Excellence” by Waterman and Peters, 1982, equated excellence with leadership. Within two years, half of the corporations featured by the authors had collapsed. Within two decades, only dust remained from the entire excellence collection. The leaders stayed rich.

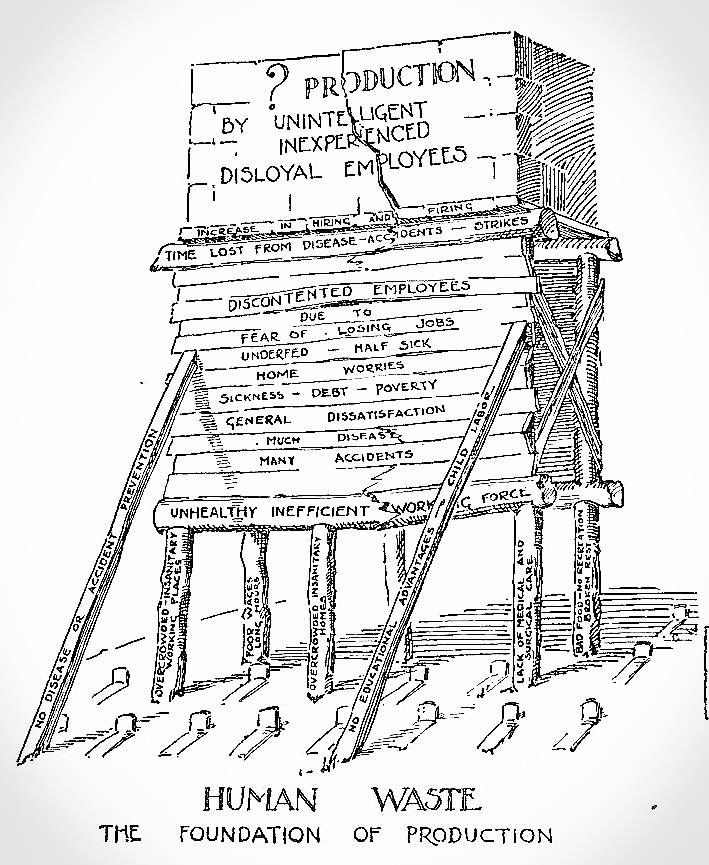

The quotes included here provide an easy-to-digest overview of organizational dysfunction and the range of ideas about remedy. Without a success reference to benchmark their author’s imagined fixes and saddled with fatally-erroneous assumptions about implementation, nothing worked, nothing lasted, and everything dysfunctional got worse. All the fuss about the wreckage caused by dysfunctional organizations, amounting to a quadrillion US dollars over the last two centuries, delivered only frustration and angst.

The champions of the miscarriage of social behavior have all passed on and nobody has taken their place. Posting the quotes is not a call for action. The quotes are a framework for knowledge development and your ideas of a fix.

Someone has spoken of corporations as being organizations “without a soul.” A number of examples indicate that great business establishments need not necessarily be soulless and that cold-blooded methods, or on the other hand those in which the element of human interests and relations appear, are merely matters of election and of the management of affairs to the end chosen.

Experience further demonstrates that the latter method is more successful in that, while adding to the sum total of human happiness, it pays economically. The reasons for this seem to be imperfectly understood, even by the organizations which have made effort to use it. But what has gone before in this book sets forth such reasons very clearly as founded on the laws of human nature. In exactly the proportion in which such laws are employed to the desired purpose, and are not contravened, industrial difficulties are avoided, unnecessary wastage of potential man power is reduced, productivity is increased and economic results are successful. It is not only a case of dollars and cents, but of dollars and sense. Successful business does not overlook the human agencies contributing to business success. Edward Lyman Munson, Col., US Army (1919)

“Our wealth is increasing as wealth has increased at no other time and place in the history of the world. However, only one-fourth of our population is benefited by this vast increase. Adam Smith, and other economists, have taught that the rate of wages depends upon “dispute,” “contract,” “custom,” in one phrase, social adjustment. On the other hand, in the theory that “labor is the residual claimant,” and in the theory of “specific productivity” now generally held, an effort has been made to show that economic law does determine wages as completely as rent or interest. To the question, why does not the increase of wealth correspondingly diminish poverty, we reply: because there is nothing in the operation of economic laws to secure a just, reasonable, or tolerable distribution of wealth.” Lester B. Ward (1915)

“There are two kinds of mentality, of which the conscious mind is the higher and responsive to will and reason; the other is the sub-conscious mind which reacts to suggestion even though the suggestion may be unreasonable. With the first, the man is a rational, self-controlled individual. With the second he is a negative self, plastic to outside suggestion and control. The latter is of great importance from the standpoint of industrial management. Consciousness is more concerned with the relation between environment and self than with that existing between any factors of the environment. This explains why, in the vast majority of cases, matters are interpreted largely on the basis of personal reactions, thereby accounting for the universal tendency to reason from the basis of individual experience and from the particular to the general. We tend to judge the world to be good or bad according to the way it treats us not according to any abstract standards of good or evil.

The original basic tendencies of man rarely act at one time in isolation from each other. Life is complex and stimuli of diverse character press in from all sides. Every influence is registered in the brain, whether the exciting agent is tangible or intangible. With the various stimuli come the inhibiting influences necessary to the harmonious relations of men in groups. Thus the behavior of man, through its excitants and restraints, tends to be a compromise of multitudinous combinations. Where two opposing tendencies neutralize each other, action is paralyzed or the mental stress may be expressed in hysteria.” Charles Henderson (1914)

A host of questions concerning the origin and development of legal and political institutions await a socio-psychological settlement. Government and law are two of the most important products, or rather sides, of the social psychic process, and the attempt to understand them without understanding it is like an attempt to understand all organic species without reference to organic evolution as a whole, or to explain attention without reference to the whole process of the mental life.

The natural history of government and of the various forms of government, when it comes to be properly written, must seek the help of social psychology to explain the phenomena with which it deals. Monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, with their variations and “perversions,” will be truly explained as phenomena only when they are shown to be expressions of the particular psychical processes which characterize particular stages of social growth, or special social coördinations. The same method of interpretation will have to be applied to the legal systems and institutions which are bound up with government.

It will be the further task of political science to show, through the facts of history and ethnography, what forms of government and of law are regularly associated with certain types of social psychic coordination. Thus it is possible that some degree of prevision may be reached as regards the relation between a society and its form of government; but no exact prevision, since, as individual psychology teaches, no two psychical coördinations can ever be exactly alike. On this account a socio-psychological interpretation of political and legal phenomena will, perhaps, be unacceptable to those who, like Comte, long for a rigid science of society, a “social physics,” which shall make possible in social life the exact prevision of the mathematical sciences.” Charles A. Ellwood: 1899

“The efficiency of labor is the greatest factor that influences productivity and profit. This is evidenced by the unceasing efforts to produce new “labor saving” devices, not only to lower costs but to reduce the various difficulties attaching to human agencies. Labor probably enters into costs more than capital invested in machinery and plants, and as a far more variable and perplexing factor. It is curious that the importance of this element has not been more fully realized and that more intelligent effort has not been made to solve the problem of increasing productivity through the man as well as the machine. Inasmuch as the purpose of an industry is to produce, an essential quality to consider in an employee is his comparative productiveness.

Where differences in productivity exist between individuals of the same group of workers producing the same thing under the same conditions and encouraged to develop their output to the full capacity, it is apparent that these relate to diversity of qualities within the individual workers themselves. Mental state enters-in that workers of enthusiasm and loyalty will show it in producing more than those not prompted by these influences, often in great degree of difference. Thus, it is economically important to determine where and to what extent such differences exist and their causes, for the worker who does more is worth more, having due consideration not only to quantity but to quality.” Edward Lyman Munson, Col., US Army (1919)

Much research has been done on the negative impact of organizational defensive routines. Many change programs have been and continue to be executed to reduce them, and the dominant focus has been to change the culture of the organization. Yet the effectiveness of cultural change programs as documented by evaluations of the participants varies from very effective to quite ineffective. And even when participants report that the programs produced positive changes, the changes have not persisted. Why?

Most individuals answer this question by saying that Organizations are too rigid and bureaucratic. They contain organizational defensive routines that inhibit learning and change. There is a lukewarm commitment to change from those at the top. I often hear additional explanations for why successful change is not sustainable.

Most busy executives do not have the time that is required to generate lasting commitment by others. It is frustrating getting people to realize that they are responsible for the problem and to stop blaming others or the system. Many executives express concern about harming their reputation if they take initiatives that are too risky. Chris Argyris (2004)

More often than not supervisors report they are being punished for missteps that inevitably happen in any operations. If missteps and failures —two essential elements of any learning — are harshly criticized, employees will shy away from taking on assignments outside their comfort zones, and organizations will lose the opportunity to develop our leaders of tomorrow. Harvard Business Review (1978)

Overall, the results of this survey were unequivocal: Respondents identified frontline managers as a linchpin of organizational success. Despite this, it revealed, most frontline managers are not equipped with the requisite resources to excel in their organizations. Respondents believed that the gap between what is expected of frontline managers and what is provided to them is adversely impacting organizational performance in myriad ways. Harvard Business Review (1989)

“The gimmicks and devices employed for purposes of manipulation will soon lose their effectiveness. The important question is management’s motives in employing the results of human relations research. If its motives are those of narrow self-interest, of finding subtler and smoother ways of bending workers to its will, the effort will be worse than useless for it will widen further the gap between management and the worker.” J. C. Worthy (1957)

-

Gain victory over yourself

-

Insist upon responding intelligently to unintelligent treatment.

-

The wise pilgrim avoids the battlefield of egos.

-

Only those who are angst-free can vent angst in others.

-

Act but don’t compete.

-

The lead people walk beside them

-

Do the tough tasks while they are small

-

To see things in the seed Lao Tzu (587 BCE)

“Those who would promote material efficiency must work hand and hand with the apostles of human efficiency and the order of precedence is given to those who are promoting the welfare of the man – body, mind and soul.” Charles Buxton Going (1908)

“I believe that just as life exists on account of certain natural laws, so also is civilization built up on the foundations of a few great moralities which organizational activities, so large a part in our civilized life, must also observe. I believe that these moralities must be enforced, not by bureaucrats, but by great leaders. I believe that the fundamentals of organization have not been invented by men, but underlie the development of all the universe and particularly govern all life, plant and animal.

I believe further that just as the wheel flanges, the swivel trucks, the elevated outside rail on the curve, the spiked rails on the ties, embedded in the leveled ballast, keep the trains on their course, so also a few, a very few practical principles systematically applied will enable us to eliminate the errors that make industrial wrecks of great enterprises, of great communities, of great civilizations. The great moralities are:

- That aptitude should have opportunity.

- That all should coordinate and cooperate for the common good.

- That public and social hygiene are essential and obligatory.

- That pleasure and joy are as essential to life as toil and rest.

- That “all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them; for this is the law.” (Golden Rule)

- That what is in each man should be developed through education and that he should also acquire general and special skill.

- That industrial competence should at all times be obligatory; that all needless losses and wastes and leaks should be eliminated.” Harrington Emerson 1920

When executives feel their “power,” their sense of control becomes inflated. They believe not only that they control things that they do not control; they come to believe they control things that cannot be controlled at all. Joseph Hallinan (2014)

“The company union has improved personal relations, group welfare activities, discipline and other matters which may be handled on a local basis. But it has failed dismally to standardize or improve wage levels, for the wage question is a general one whose sweep embraces whole industries, the States, and the nation. Without wider areas of cooperation among employers there can be no protection against the nibbling tactics of the unfair employer or of the worker who is willing to degrade standards by serving for a pittance. Major questions of self-expression and democracy are involved.

The company union, initiated by the employer, exists by his sufferance; its decisions are subject to unimpeachable veto. The highest degree of cooperation between management and labor is possible only when either side is free to act or withdraw or that the best records of mutual respect and mutual accomplishments have been made by employers dealing with independent labor organizations.” Robert R.F. Wagner, Senator from NY (1927)

“Before we are fully prepared to consider, in all its length and breadth, the important proposition that society can and should seriously undertake the artificial improvement of its condition upon scientific principles strictly analogous to those by which the rude conditions of nature have been improved upon in the process which we call civilization; before we are wholly ready to enter upon an argument to prove the feasibility, the desirability, and the right of society, as such, to adopt an aggressive reform policy guided entirely by scientific foresight rendered possible by an intelligent acquaintance with the fundamental laws of human action; before we can justly contemplate man in his social corporate capacity assuming the attitude of a teleological agent and adopting measures in the nature of final causes for the production of remote beneficial effects – before we can properly rise to this position, it seems necessary that we should first seek to obtain as just and true a conception as the human mind is capable of grasping, of the real and precise relations which man and nature mutually sustain to each other.” Lester F. Ward (1881)

“A concept of desired application to a specific purpose is so developed in the individual that neither its source nor purpose nor the fact of acceptance may be recognized. In this way a man accepts and supports an idea as his own, not realizing that it came from outside and was not of internal and individual origin. This is because impressions of all kinds bow in upon him and all exert their influence upon ideas and acts. The individual does not have the power to automatically receive only such mental impressions as he might have decided he would like to accept. Those artificially and deliberately created present no difference in appearance or result than they would have if they had been the product of chance. But if suggestion is so clumsily conveyed as to show its artificiality, it is at once resented.” John Carl Cabe (1909)

“I shall not urge details of dealing with men any more than to urge details of tools and materials we see, but I do urge that as the laws of nature are utilized by us all after keen inquiry into them in the mechanical and material side of our work, so the laws of human nature shall be given at least as keen study in the living and productive side of our work. For, since both the laws of mechanics and the laws of human nature are but a partial manifestation of the law of the universe, there can be no harmony and no basis for permanent peace in reaching for the highest production until we have readjusted our factories so that they operate in accordance with the laws of human nature.” Ordway Tead (1895)

Making slavery unlawful provided the setting for treating the workers who took their places – with detachment, abuse and indifference far worse than slavery. George B. Hugo (1901)

“Preamble: The alarming development and aggressiveness of great capitalists and corporations, unless checked, are leading to the pauperization and hopeless degradation of the toiling masses. The method of remedying this evil is first the organization of all laborers into one great solidarity. The direction of their united efforts towards the measures that shall, by peaceful process, evolve the working class out of their present condition in the wage system into a cooperative system. It proposes to exercise the right of suffrage to assist the natural law of development. It is the purpose of the Order to establish a new and true standard of individual and national greatness.” The Knights of Labor (1880)

“It is one thing to discover the cause of the trouble; it is quite another to get the victim of the conflict to realize and admit that you have for arrived at the truth of the matter. After all, we can do nothing for another beyond putting him in the way of doing something himself. The solution lies in getting him to face reality and to accept responsibility for what has been troubling him. Once this has been done, the remedy takes care of itself. It is fighting shadows that causes most maladjustments. Once a man has it brought home to him just what the real trouble is, he will see his own solution without further help from outside. Facing reality is the hard task. It is much easier and more self-satisfying to continue to evade the responsibility by placing the blame elsewhere than on our own shoulders even though this face-saving evasion accomplishes nothing in the way of bettering our situation.” John N. Bury (1937)

“Work is not a commodity, another inanimate element in the process of manufacture. It is inseparable from the personality of the worker. To promote increases in process productivity, attention must be centered on the worker, upon the congenital and acquired human traits and modes of action which comprise his personality. The natural tendency of the process owners is this regard is to make human values secondary to machine values. While care for the machine is normal practice, care for the worker is not.

The Establishment invoked the policy of Laissez Faire buttressed by the opinion that held generally, even by enlightened members of the employing and governing class, that the degradation of the workforce and their enslavement to the machine was part of the necessary order of nature – the inevitable result of the operation of natural laws which no effort of government, public opinion, or philanthropy could change.” Lionel Edie (1917)

“In the first place, the United States is a market economy, not a government-planned economy. Individual firms reap the fruits of their comparative economic advantages and suffer the consequences of economic miscalculations as well. The recent experience of the gigantic Chrysler Corporation demonstrates the futility of workers relying on corporate viability as protection for their jobs, salaries or pensions.

Now their jobs offer low pay, little training, no promotion, arbitrary discipline and constitute the “secondary” labor-market. The larger firms satisfy the constant demand in the industry and provide “primary” labor market jobs. Primary jobs offer better pay, training on the job, some advancement and due-process protection against arbitrary discipline. At the most general level then, the planning of human-resource opportunities for workers is the consequence of product market decisions made by a number of employers more or less independently in order to deal with uncertainty in the product market and maximize return on their investment. Such decisions are not in the control of one firm. Thus, human-resource planning in a capitalistic market economy is a contradiction.

The second problem is more mundane; planning just doesn’t amount to much in practice. Two years ago, we studied the human resource planning efforts of two large private sector employers. Our findings can be summed up in a word: smokescreen.

Financial considerations dominated the long-range planning effort in each firm. The human-resource considerations were strictly secondary, despite their reputations for sophistication in this field. For example, in one company, if divisional human-resource projection failed to conform with the financial projections of corporate managers, the planning staff simply changed their numbers at corporate headquarters. The new numbers never sifted back to the divisions, so it is difficult to imagine how much the final “human resource plan” affected operations. In the second firm, the financial plan preceded the human-resource plan each year, so the financial estimates dominated subsequent human-resource projections.” James W. Driscoll (1980)

The handling of the American worker seems to have been attempted in defiance of the laws of human nature. Some of the methods have been largely adopted from feudal society. Whether they were applicable to the American mental make-up, or to present day conditions, was not duly considered. Some business executives, deliberately, if innocently, attempt to repress natural instincts. It must be emphasized that all administrative methods not in accordance with the laws governing psychology will fail. Morale work is governed by general principles only. Rules will not apply, for methods which may be successful at one time or place may be successful only in part, if at all, under other conditions. The early symptoms of low morale should be recognized and their causes inquired into and corrected, for morale work is essentially not repair work but work of prevention, though both may go hand in hand. Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

“Wherever human beings are grouped together in mutual endeavor or for the accomplishment of a definite task, attitude is bound to be a controlling factor in their work. That their mental state, their will to do, their cooperative effort – all of which are synonymous – bear a true relation to their output, productivity and the success of the joint undertaking, is so obvious and has been proven so often as to require no supporting argument.

It is regrettable that modern industry has failed so often to comprehend this basic and vital economic truth or, comprehending it, has failed to grasp the opportunity and turn it to practical advantage. Directive and administrative energy has been turned too exclusively along mechanical and operative lines with disregard of the intrinsic and vitalizing psychological factors of producing.” Arthur Twining Hadley (1901)

“At present the working man toils on through the period of a dreary existence, content if he can secure enough of the common necessities of life. He leaves behind him a family with no heritage but his own – no means to live but by hiring out to work for the benefit of others. Our descendants who wish to raise themselves from the conditions of wage earners, but they wish in vain. They cannot approach a field on which the capitalist has not set his mark and each succeeding age their condition becomes more and more hopeless.

They read the history of their country and learn there was a time when their fathers could have preserved balance. When our posterity look back to the opportunity that we are now losing, they will not bless our memory if we leave them nothing but a heritage of toil and dependence.” Winston Lloyd Garrison (1840)

“It is true that the complexity of the general industrial morale problem is very great, including as it does the hundreds of possible varieties of men and women, races and creeds, skill and awkwardness, trades and professions, classes and diversity of environmental conditions, many of which do not enter into the problem of military morale. Large organizations have proportionately greater industrial difficulties because of the greater number and diversity of their elements. As the aggregation of men in masses increases liability to epidemic of infectious disease, so it increases the problems brought about by infectious thought. Nevertheless, it is possible to demonstrate that the problem of industrial morale is practically solvable to an extent far greater than is usually appreciated.

It seems perfectly feasible to reduce considerably many of the points of unnecessary friction between the employer and employee to their mutual advantage and profit. Many repressions of perfectly natural human traits can be done away with by wise management, and the reactions which spring from them, such as lowered production, increased labor turnover, strikes and lockouts, be avoided. Any such conditions as are left unremedied will continue to serve as irritants and result in corresponding loss in efficiency – that is, in productivity.” Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

“The greater productivity of labor must not only be attainable, but attainable under conditions consistent with the conservation of health, the enjoyment of work, and the development of the individual. In the task of ascertaining whether proposed conditions of work do conform to these requirements, the laborer should take part. He is indeed a necessary witness. Likewise in the task of determining whether in the distribution of the gain in productivity justice is being done to the worker, the participation of representatives of labor is indispensable for the inquiry which involves essentially the exercise of judgment.” Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1915)

The bottom line to all the paradoxes is this: managements at all levels, create by their own choice, a world that is contrary to what they say they prefer and contrary to the managerial stewardship they espouse. It is as if they are compulsively tied to a set of processes that prevent them from changing what they believe they should change. W. Edwards Deming (1981)

“Invoking managerialism is futile. It approaches change using the mindsets and techniques of the command and control workplace and it does not work.” Brad Jackson (2001)

“Not rarely, problems outwardly disciplinary have their basis in matters of executive maladjustment. It is thus obvious that the constructive instinct is one to be turned to valuable organizational account. But to do so most efficiently, the personality of the worker must be allowed to enter. The individual must be given to realize that the task assigned to him is his own particular job, or he will have little incentive to put thought and labor into it. Every human creation, no matter how simple or complex, is an embodiment of thought and concept in which one or more persons had pride of origination and development. Every act offers opportunity for self-expression and self-assertion.” Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

“North Americans have had little trouble living with each other as citizens during the recent centuries. Since the industrial revolution geared up, in exception, there has been scant and fleeting success in living with each other as employer and employee. Clearly the same man has a very different status regarding the state from what he has regarding the organization. As a citizen, he has a good measure of freedom of speech. He can criticize those in authority with impunity and take every opportunity to do so. He has a voice through the ballot box, in the selection of those who are to govern him, and he can exert his influence upon them by this power after they are selected. He has a constitution and a definite code of laws which state in no uncertain terms just what he can do and what he must do. Should he be accused of violating those regulations, he has the right to a hearing in the form of a trial by a jury of his equals.

Evaluate the same aspects in industry. The wisdom gained by bitter experience orders that if he wishes to exercise his right of free speech, he will do so where it will not be heard by anyone else, fellow worker or employer, if what he says can be construed as unfavorable to the management. He has no voice in in the matter of who is to be his supervisor nor has he power to change or correct the supervision if he finds it incompetent, counterproductive or unjust. He has no Bill of Rights as an employee and no adequate idea as to exactly where his duties and responsibilities begin and end. He does not know the full extent of his privileges and perquisites. When he is suspected of failing to meet the nebulous rules and regulations of the organization, he is faced with the charges by a man who is at the same time his accuser, his prosecutor, his jury, and his executioner.

If this paradox, the discrepancy between the worker and the citizen, was imposed on us by law, rather than by custom, we would rebel as we did over taxation without representation. On this contradiction is based whatever stability there might be in the workaday world of industry. Freedom of speech, not a code of silence, is the safety valve of organizational dysfunction.” Albert Walton (1921)

“All of them were very alive and were making great changes in short periods, both in system and personality. One was passing from autocracy into government by employees; another from scientific management into unionism; another from welfare into self-government; another from political to industrial form of government.

One interesting fact was found: the sudden or gradual moral conversion of an employer from business to humanity. Employees noted it, and could not at first believe it, or were still incredulous, and told us about it, and so did the employer himself. In some cases it was unionism or strikes that did it. In others it was business foresight of the labor problem. In others it was sermons by an industrial evangelist.

We noted also certain obvious contrasts. In one case, not however included in this book, output had fallen off two-thirds, wages had doubled and high prices took care of both. In others efficiency had increased nearly as much as wages, so that the increased cost of living was nearly paid for by increased output per man. In some cases wages had not kept up with the cost of living; in others they had exceeded the increased cost. In some cases labor-turnover was down at astonishingly low figures compared with the industrial world in general. In some cases seasonal industries had been stabilized so that no employee is laid off. In others the rapid growth of the business has overcome instability of employment.” John R. Commons (1919)

“It is important that the desires of the individual as to choice of task should be helped as far as possible and not thwarted. It has already been stated that what human beings want to do they usually do well, and they do it well because they want to do it. This of course has a direct bearing on productivity. It is short-sighted economic policy to attempt to meet a special need at the expense of the sacrifice of interest and the checking of the energy flowing from constructiveness.” Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

Too many of us have stopped too soon on the path of scientific development of our industries. The man is infinitely well worth study and infinitely more difficult to study than the machine. We all believe that cleaner and better things are attainable than a constant struggle between profits at the top and penury at the bottom in the same establishment. Joseph Tiffin 1877

“Delegated authority to control, and personal ability to control, is as far apart as the poles. Efficiency at the machine and efficiency over men require very different qualifications, and the overlooking of this fact will bring about many unnecessary frictions and difficulties. The close contact between the workers and their immediate supervisors makes this matter of special importance. On the other hand, unsympathetic policies handed down from above as to the handling of men will be carried out by loyal subordinates even if they are in conflict with the ideas of the latter. One result of the poor handling of the human element is the impairment of interest and initiative and a resulting slowing down in productivity. There may be direct reaction against repression, or a lack of stimulus for the expenditure of a fair degree of energy. Either cause affects result.” Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

“An altruistic quality of sympathy is evoked toward a superior from his organization if the men see that he is particularly concerned with the welfare of the weaker and those more in need of assistance. Sympathy is capitalized for efficiency in result. The value of good will between chief s and workers is an asset which may be estimated in millions of dollars by a great industrial organization. A greater output of a product of better quality is the result of sympathy in a mutual purpose. The organizations whose managers are trusted and respected by their men will maintain higher standards for accomplishments. No superior, if only for personal and selfish reasons, can afford to affect to ignore what the men think of him, for upon the relative zeal and degree of thoroughness with which they carry out his orders rests his own reputation.” Akin Karoly (1902)

In 1913 USA production efficiency had dropped to 60% from previous higher levels. By 1920 the figure had fallen to 40%. No one disputes the attainable benchmark efficiency at 90%. Most people treat this ongoing calamity as of no consequence. Why does management combat successful methods? Albert Grimshaw (1917)

“Ordinarily the intangibles of psychology receive little attention and consideration in industrial affairs, but if these are aroused in them, the reaction is much like that expressed by the foreman whose champion gang at the Hog Island ship yard set a new record for riveting, “According to my way of figuring, this thing called morale is blamed important.” All business men realize that production is not a smooth and orderly process at all times and that with exactly the same physical equipment of plant, machinery, material and capital invested, and with the same number of workers, elements of morale affecting the latter will enter to force output up or down. This may be so variable as to run the gamut between profit and loss.” Edward Lyman Munson (1919)

“The inanimate elements of the labor-saving process assume a complementary boost in the effective use of human energy, human abilities, and of the human will-to-work to deliver the success of the process and the future of our civilization.

In perfecting the machines and the tools which the worker uses in the economic arts, we have hardly attempted to improve the worker himself. If he were considered as an instrument, a tool, a motor, he would necessarily be placed in the first rank of all instruments, all mechanical agents, since he has the immeasurable advantage of being an instrument who observes and corrects himself, a self-stopping motor which functions with the motivation of its own intelligence, and which perfects itself by thinking not less than by work itself.

Management has always selectively and deliberately considered labor as the opponent in a zero-sum game. In 1880, Frederick Winslow Taylor was struck by how little management, handicapped by prejudices handed down from the past, knew about their workers and how erroneous their notions as to the role workers play in creating their fortunes. Never appreciating that when they fail the worker, by withholding instruction, conditions of work, and morale, they fail their own stated purpose. Even when confronted with successful applications of psychological principles, management continued to pursue policies and practices proven to fail.” John Leitch (1914)

“That the owners and agents of factories should see this whole matter in a different light from that it wears to us, we deem unfortunate but not unnatural. It is hard work to convince most men that a change which they think will take a thousand dollars out of their pockets respectively is necessary or desirable. We must exercise charity for the infirmities of poor human nature. But we have regretted to see in the Whig journals of New Hampshire indications of hostility to the Ten Hour regulation, which we hardly believe being dictated by the unbiased judgment of their conductors.

What show of argument they contain is of the regular Free Trade stripe and quite out of place in journals favorable to protection. Complaints of legislative inter meddling with private concerns and engagements, vociferations that Labor can take care of itself and needs no help from legislation – that the law of Supply and Demand will adjust this matter, properly belongs to journals of the opposite school.

We protest against their unnatural and ill-omened appearance in journals, of the true faith, to talk of the freedom of labor, the policy of leaving it to make their own bargains, when the fact that a man who has a family to support and a house hired for the year is told “If you will work thirteen hours per day, or as many as we think fit, you can stay. If not, you can have your walking papers; and well you know that no one else hereabout will hire you” – is it not the most egregious flummery?” Horace Greeley 1845

I would gladly hear any man compare the justice that is among them with that of all other nations; among whom, may I perish, if I see anything that looks either like justice or equity; for what justice is there in this: that a nobleman, a goldsmith, a banker, or any other man, that either does nothing at all, or, at best, is employed in things that are of no use to the public, should live in great luxury and splendour upon what is so ill acquired, and a mean man, a carter, a smith, or a ploughman, that works harder even than the beasts themselves, and is employed in labours so necessary, that no commonwealth could hold out a year without them, can only earn so poor a livelihood and must lead so miserable a life, that the condition of the beasts is much better than theirs?

For as the beasts do not work so constantly, so they feed almost as well, and with more pleasure, and have no anxiety about what is to come, whilst these men are depressed by a barren and fruitless employment, and tormented with the apprehensions of want in their old age; since that which they get by their daily labour does but maintain them at present, and is consumed as fast as it comes in, there is no overplus left to lay up for old age.

Is not that government both unjust and ungrateful, that is so prodigal of its favours to those that are called gentlemen, or goldsmiths, or such others who are idle, or live either by flattery or by contriving the arts of vain pleasure, and, on the other hand, takes no care of those of a meaner sort, such as ploughmen, colliers, and smiths, without whom it could not subsist? But after the public has reaped all the advantage of their service, and they come to be oppressed with age, sickness, and want, all their labours and the good they have done is forgotten, and all the recompense given them is that they are left to die in great misery.

The richer sort are often endeavouring to bring the hire of labourers lower, not only by their fraudulent practices, but by the laws which they procure to be made to that effect, so that though it is a thing most unjust in itself to give such small rewards to those who deserve so well of the public, yet they have given those hardships the name and colour of justice, by procuring laws to be made for regulating them. Sir Thomas More (1516) “Utopia” (edited by Erasmus)

All great movements of history and prehistory have been the products of unrest and man’s struggle to make or find an environment that better suits his nature and his needs. Today we are in the midst of a Copernican revolution in industry and are beginning to realize that it was made for the better development of man, and not conversely. It can never be stable until it fits human nature and needs.

But let me say at the outset that the nascent but inevitable advent of democracy into industry is not to be attained by any Bolshevik program of confiscation or nationalization of capital; nor by any form of government socialism, or by the French or any form of syndicalism; nor by any modernization of the medieval guilds; nor by any development yet in sight of the efficiency system, which has so far contributed almost as much to the discontent of labor as it has to the effectiveness of the organization; nor even by the full program of the Whitley reports.

Permanent and settled industrial peace and good-will can only be found in a full and unreserved cooperation between capital and labor, with some complete scheme of joint control and profit-sharing, involving more knowledge by the laborer of the business as a whole and more loyalty to it. This alone can bring harmony, avoid the excessive waste of friction, ill-will, soldiering on the job, labor turnovers, strikes, of which an official report a few months ago told us there were three hundred sixty-five, or one for every day of the year, on at that time in this country-and all the other wastage of energy from unemployment to sabotage. All these disorders which are so ominous for the business and economic future of this country and its supremacy in the markets of the world are, in a sense, of psychic origin, and the cure must be sought by a better knowledge and a wiser regimentation of the mind of labor. G. Stanley Hall (1920)

One of the main forces in keeping economic motive on a low moral level has been the doctrine that selfishness is all we need or can hope to have in this phase of life. Economists have too commonly taught that if each man seeks his private interest the good of society will take care of itself, and the somewhat anarchic conditions of the time have discouraged a better theory. In this way we have been confirmed in a pernicious state of belief and practice, for which discontent, inefficiency, and revolt are the natural penalty. A social system based on this doctrine deserves to fail.

When pressed regarding this matter economists have not denied that their system rests on a partial and abstract view of human nature; but they have held that this view is practically adequate in the economic field, and have often seemed to believe that it sufficed for all but a negligible part of human life. On the contrary, it is false even as economics, and we shall never have an efficient system until we have one that appeals to the imagination, the loyalty, and the self-expression of the men who serve it.

By a sense of security I mean the feeling that there is a larger and more enduring life surrounding, appreciating, upholding the individual, and guaranteeing that his efforts and sacrifice will not be in vain. I might almost say that it is a sense of immortality; if not that, it is something akin to and looking toward it, something that relieves the precariousness of the merely private self. It is rare that human nature sustains a high standard of behavior without the consciousness of opinions and sympathies that illuminate the standard and make it seem worthwhile. It lies deep in the social nature of our minds that ideals can hardly seem real without such corroboration.

In a still more tangible sense I mean a reasonable economic security. A man can hardly have a good spirit if he feels that the ground is unsure beneath his feet, that his social world may disown and forget him tomorrow. There is scarcely anything more appalling to the human spirit than this feeling, or more destructive of all generous impulses. It is an old observation that fear shrinks the soul; and there is no fear like this. The soldier who knows that he may be killed at any moment may yet be perfectly secure in a psychological sense; secure of his duty and of the sympathy of his fellows, his mind quite at peace; but this treachery of the ground we stand on is like a bad dream. As one will shrink from attaching himself in love and service to a person whom he feels he cannot trust, so he will from giving his loyalty to an insecure position. It is impossible that such tenure of function as now chiefly prevails in the industrial world should not induce selfishness, restlessness, and a service-only mercenary. Judged by such standards, our present order is inefficient, because its tasks are so largely narrow, drudging, meaningless, and inhuman.

While it is not indispensable, in order to secure emulation in service, that the work should allow of self-expression and so be attractive in itself, yet in so far as we can make it self-expressive we release fresh energies of the human mind. The ideal condition is to have something of the spirit of art in every task, a sense of joyous individual creation. We are formed for development, and an endless, hopeless repetition is justly abhorrent. No matter how humble a man’s work, he will do it better and in a better spirit if he sees that he can improve upon it and hope to pass beyond it. As regards the individual himself, self-expression is simply the deepest need of his nature. It is required for self-respect and integrity of character, and there can be no question more fundamental than that of so ordering life that the mass of men may have a chance to find self-expression in their principal activity.

Self-expression springs from the deeper and more obscure currents of life, from subconscious, unmechanized forces which are potent without our understanding why. It represents humanity more immediately and its values are, or may be, more vital and significant than those of the market; we may look to them for art, for science, for religion, for moral improvement, for all the fresher impulses to social progress. The onward things of life usually come from men whose imperious self-expression disregards the pecuniary market. In humbler tasks self-expression is required to give the individual an immediate and lively interest in his work; it is the motive of art and joy, the spring of all vital achievement.

Closely related to this is the sense of worthy service. No man can feel that his work is self-expressive unless he believes that it is good work and can see that it serves mankind. If the product is trivial or base he can hardly respect himself, and the demand for such things, as Ruskin used to say, is a demand for slavery. Or if the employer for whom a man works and who is the immediate beneficiary of his labors is believed to be self-seeking beyond what is held legitimate, and not working honorably for the general good, the effect will be much the same. The worst sufferers from such employers are the men who work for them, whether their wages be high or low.

As regards the general relation in our time between market value and self-expression, the fact seems to be something as follows: Our industrial system has undergone an enormous expansion and an almost total change of character. In the course of this, human nature has been dragged along, as it were, by the hair of the head. It has been led or driven into kinds of work and conditions of work that are repugnant to it, especially repugnant in view of the growth of intelligence and of democracy in other spheres of life. The agent in this has been the pecuniary motive backed by the absence of alternatives. This pecuniary motive has reflected a system of values determined under the ascendancy, direct and indirect, of the commercial class naturally dominant in a time of this kind. I will not say that as a result of this state of things the condition of the handworkers is worse than in a former epoch; in some respects it seems worse, in many it is clearly better; but certainly it is far from what it should be in view of the enormous growth of human resources. In the economic philosophy which has prevailed along with this expansion, the pecuniary motive has been accepted as the legitimate principle of industrial organization to the neglect of self -expression.

Production has not always lacked ideals, nor does it everywhere lack them at present. They come when the producing group gets a corporate consciousness and a sense of the social worth of its functions. The medieval guilds developed high traditions and standards of workmanship, and held their members to them. They thought of themselves in terms of service, and not merely as purveyors to a demand. In our time the same is true of trades and professions in which a sense of workmanship has been developed by tradition and training.

A good carpenter, if you give him the chance, will build a better house than the owner can appreciate; he loves to do it and feels obscurely that it is his part to realize an ideal of sound construction. The same principle ought to hold good throughout society, each functional group forming ideals of its own function and holding its members to them. Consuming and producing groups should cooperate in this matter, each making requirements which the other might overlook. The somewhat anarchical condition that is now common we may hope to be transitory. Charles Horton Cooley (1918)

American organizations of all kinds have peculiarly lacked balance. In our national and State governments the mental type has predominated—lawyers; in our city governments the vital type has predominated—the glad-hand politician without ideals; in the railroads and other great businesses the motive type has predominated to the exclusion of ideals and of human sympathy. Congress and the Supreme Court and the President are viewed with distrust by the whole country because we, the workers, are being subjected to theories, to protection and to free trade theories, to the theory that big combinations and mergers are inimical to the public welfare.

In the business world, as in all occupations involving human beings, to illustrate the need of selected habits and adaptive variability in a field too often overlooked, the manner in which men are treated largely determines the success of manager or foreman. Certain methods, called drive, have been acquired from the environment, education, or training, and they are followed. These managers know no other way.

Virtually all psychologists observe that business managers commonly miscalculate the mind of the worker in that they attribute his shortcomings and misbehavior to willful and deliberate perverseness. The repeated complaint made by management is that the faults, sins and inefficiencies of labor are the result of a pernicious act of will. The corresponding assumption is that labor ought to change its mind by an act of will, ought to see the reasonable way of behavior, and ought to revise its mental outlook as a matter of volition and self-control.

This common view held by management grossly overrates the element of detached and independent reason and grossly underrates the element of impulsive human nature. The faults and perversities of labor are due to natural causes, and certain pioneer managers have found that by changing the natural causes, they eliminate the faults and perversities, and substitute for them sound mental attitudes and efficient behavior.

Psychologists generally emphasize that the so-called faults of labor are due to unscientific methods of management which do not rightly encourage the “wholesome tendencies” of human nature nor “curb the pernicious tendencies.” In other words, psychology indicates that the responsibility for the misconduct of labor rests not with labor, but with management. Executives cannot shift the blame upon a perverse human nature on the part of the workers, for their human nature is as good as that of anybody else. The blame rests upon executives for not having developed methods of management which direct the human nature of the workers in the proper channels.

At the outset, therefore, psychology presents a strong challenge to management to accept the responsibility for reconstructing business practices so as to “help the better and repress the pernicious tendencies” of labor. But this challenge comes face to face with many traditional axioms of management and with a background and outlook which often are slow to change. A few pioneer business men here and there acquire the viewpoint of modem psychology and demonstrate in practical achievements what can be done. The rapidity with which the rank and file of executive management come to understand the mind of the worker in a manner similar to that of the pioneer managers determines the rate of industrial progress. Lionel E. Edie (1920)

There is a very pregnant sense in which the war is not ended but only transferred to other fields to be carried on by other agents. Those of us who have not smelled powder must now come forward and take up the battle which is waged against conservatism and inertia, by which things tend to slip back into the same old ruts as before if we do not mobilize and use all the unprecedented opportunities and incentives to reform to make the educational, industrial, social, political and religious world fitter to live in; for otherwise we break faith with the millions who have died. Our foes are timidity and laziness in this new spiritual conflict to which the battle of arms has bequeathed its precious legacy. To say that reforms are now needed, though hard and dangerous, is true, but to leave them unattacked is a slackerdom unworthy of the spirit of our armies in France. The new struggles we ought to enter upon are the harvest of victory, and are harder and will take far longer than the war itself.

Our task, thus, is nothing less than to rehumanize industry, to break down the disastrous partition that has grown up between brain-work and hand-work, to appeal at every step to mind lest we add to the degradation of labor, remembering that the brain in its evolution was hand-made and that in all progressive periods of the past the two have always gone and grown together. We must find a way of putting not merely head and intelligence but heart into work, as also was the case of yore. We must search everywhere for the culture elements which are inherent in every industry and even in every process, and which it is the tragedy of modem industrialism to have lost. Work has made and it alone can perfect man; hence we must attempt to restore or else create a morale in every great branch of industry. All this stupendous task I believe can be wrought out, because nearly every item of it has been accomplished somewhere at some time. Jeremiah W. Jenks (1919)

There can be no doubt that, in the case of the larger industrial combinations, the belief on the part of the managers that a virtual monopoly could be secured was a powerful element toward bringing about their formation. The pride of power, and the pleasure which comes from the exercise of great power, are in themselves exceedingly attractive to strong men. As one with political aspirations will sacrifice much and take many risks for the sake of securing political preferment in order that he may in this way rule his fellows, so a successful organizer of business derives keen satisfaction from feeling that he alone is practically directing the destinies of a great people, so far as his one line of business is concerned. Walter E. Clark (1917)

Certain institutions have been found by experience to work better than others; i.e., they give more scope to the wholesome tendencies, and curb the pernicious tendencies. Such institutions have also a retroactive action upon those who live under them. Helping men to goodwill, self-restraint, intelligent cooperation, they form what we call a solid political character, temperate and law-abiding, preferring peaceful to violent means for the settlement of controversies.

Where, on the other hand, institutions have been ill-constructed, or too frequently changed to exert this educative influence, men make under them little progress toward a steady and harmonious life. To find the type of institutions best calculated to help the better and repress the pernicious tendencies is the task of the philosophic enquirer, who lays the foundations upon which the legislator builds. A people through which good sense and self-control are widely diffused is itself the best philosopher and the best legislator, as is seen in the history of Rome and in that of England. It was to the sound judgment and practical quality in these two peoples that the excellence of their respective constitutions and systems of law was due, not that in either people wise men were exceptionally numerous, but that both were able to recognize wisdom when they saw it, and willingly followed the leaders who possessed its government, relapsed wearily after their failure into an acceptance of monarchy and turned its mind quite away from political questions.

More than a thousand years elapsed before this long sleep was broken. The modern world did not occupy itself seriously with the subject nor make any persistent efforts to win an ordered freedom till the sixteenth century. Before us in the twentieth a vast and tempting field stands open, a field ever widening as new States arise and old States pass into new phases of life. More workers are wanted in that field. Regarding the psychology of men in politics, the behaviour of crowds, the forms in which ambitions and greed appear, much that was said long ago by historians and moralists is familiar, and need not be, now, repeated. Arthur Stone Dewing (1920)

During the first three weeks of the application of the slide rules to two lathes, the one a 27 inch, the other a 24 inch, in the larger of these shops, the output of these was increased to such an extent that they quite unexpectedly ran out of work on two different occasions, the consequence being that the superintendent, who had previously worried a good deal about how to get the great amount of work on hand for these lathes out of the way, suddenly found himself confronted with a real difficulty in keeping them supplied with work.

But while the truth of this statement may appear quite incredible to a great many persons, to the writer himself, familiar and impressed as he has become with the great intricacy involved in the problem of determining the most economical way of running a machine tool, the application of a rigid mathematical solution to this problem as against the leaving it to the so-called practical judgment and experience of the operator, cannot otherwise result than in the exposure of the perfect folly of the latter method. Carl G. Barth (1899)

Organization is older than history. The earliest documents, such as the code of Hammurabi, show the evidences of many generations of systematized social life. The real pioneers are the unknown promoters of the Stone Age and the system-makers of the Bronze Age. Long ago almost every conceivable experiment in organization was first made. The records of history tell us of large units and small ones, of great and slight differentiation of functions, of extreme division and extreme concentration of authority, of mild and severe sanctions, of appeal to system and appeal to, passion, of trust in numbers and trust in leadership. Of the vast variety of units of organization through which human intelligence has worked, and through which human purposes have been achieved, or thwarted, the greater part has passed away; and the names of them, even, have been forgotten. In politics, the evolution has passed through the horde, the patriarchal family, the clan, and the classical city state.

We are still eagerly searching for the most elementary principles of administration. With countless generations of experience, in the conduct of affairs, behind us, the individual business executive of today is feverishly trying to broaden and intensify his personal experience—to live fast and hard—so that, in the short span of his life, he may discover de novo, for himself, the principles and policies required in the government of the complicated economic organizations of the present day. Since a knowledge of the principles of administration is now of so great importance, we should add to the agencies now being established, for the study of current performance, a provision for the systematic review of the history of administration.

An analogy exists between the present needs of the American business executive, into whose hands in a generation a great increase in power has come, and the needs of the German army officers before the development of that splendid system which made Germany the leading military power of the world. A hint may, therefore, be gained from their experience. The Prussian General Staff and War College were organized to gather all engineering, topographic, and other technical knowledge, which could be made of use in war. But, especially, there was entrusted to them the function of reviewing military history in a scientifically thorough manner, to obtain from it the maxims and principles which possess validity for future operations. In the hands of general historians, history is worth less for military guidance; but to Scharnhorst, von Clausewitz, von der Goltz, von Moltke, and the other students of the General Staff, is due the credit of having so sifted their facts, and so brought them to bear, in the criticism of principles, that they have made them a firm foundation for the scientific conduct of war.

Many men of affairs are much prejudiced against the invasion of business by science and theory. They conceive of these things as something new and untried, and something opposed to experience. A certain excuse for this view exists in the fact that the scientific method has, thus far since its discovery, been applied most prominently to facts which ordinary experience does not furnish, but which are attainable only through the somewhat rigid and refined methods of the laboratory. Many persons have concluded from this that the method cannot be applied to the facts of ordinary experience. Edward D. Jones (1912)

The scientific method is the analysis of problems into their elements; an extensive and thoroughly adequate collection of data; an exact and truthful classification of facts on the basis of their nature; such an arrangement and grouping of them as will best reveal agreements, differences, and concomitant variations between them; and the making of inferences, or the discovery of new facts, by means of induction, deduction, and analogy. The new truths, or inductions, are then subject to criticism and test in every possible way.

The scientific method calls for the eradication of prejudice which may interfere with the just estimate of any facts; and it requires open-mindedness, or willingness to receive new facts at any time, and to make such revisions in conclusions as may be required. This method is universal in its applicability. It can be set at work upon the organizations of which we find records in history, as well as upon the fossil remains of organisms in the earth’s strata. It can work upon data which are the product of the most haphazard, partial, or impassioned of experiences, as it can upon the exactly controlled processes of a laboratory experiment. The results obtained will, of course, depend upon the quality of the materials furnished to it, and upon the degree to which the material can be controlled to compel it to reveal its true nature fully and clearly.

It is now obvious that on such important matters as repairs on locomotives the Taylor plan is the most efficient for prevention of accidents. In our own experience, we have found that increasing productivity prevents accidents. In fact, we know that it is the one simplest and most efficient method of protecting the workers from injury and loss of life. Albert Spencer (1902)

In strategy, which includes the general movements of a military campaign, preliminary planning is of course impossible. The distances separating the several divisions of a great army, the time which would be required to make voluminous reports to headquarters, and to receive back detailed instructions, and the innumerable local conditions which cannot be adequately grasped by one at a distance, make it impossible that highly centralized control should exist. Here the flexibility of the German army system is shown.

In contrast to the rigid plan of mobilization imposed by central authority, when the campaign is once underway, and changing and uncertain conditions have to be dealt with, the headquarters becomes responsible only for the general features of the plan of operations. Authority immediately passes down the line to army commanders, and regimental and company officers, lodging as close as possible to the time, place, and agencies of specific action. The army then becomes, not a mechanism under the thumb of a single leader, but an organism with great liberty of action, and corresponding responsibility, resting upon the parts.

Von Moltke once said that nothing should be ordered which it was conceivable could be carried out by the proper officers without orders. Certain it is that the orders from headquarters in the Austrian and Franco-Prussian wars were very few in number, and composed of but a few sentences each. Passing from higher to lower units, orders from the leaders of separate armies, corps orders, and division orders, were, of course, progressively firmer and more detailed. In the modern tactics of engagements, a similar rule as to the location of authority is followed.

While each army headquarters retains sufficient control to insure harmony of plan, details of execution are entrusted largely to the officers on the field, and in direct command of the minor divisions of troops. The old ramrod drill movements of troops on the field of battle are no longer possible. Discipline is now interpreted broadly that each individual shall apply sound principles in every emergency. The fear of minor mistakes is as nothing, with modern military administrators, in comparison with the energy of troops and lower officers by unduly suppressing initiative. All this manifestly calls for a superior class of executives of all ranks, adequately prepared for their duties. Edward D. Jones (1912)

It is clear that for the lodging of any administrative function, and the resting of the corresponding responsibility, there must be a certain ideal point in the administrative hierarchy of any organization. This point is where the problem of keeping in touch with the specific details of the agencies of the action controlled, is approximately equal in difficulty to the problem of keeping in touch with the general plan of which that action is a part. To move a function from this point towards headquarters is to lose touch with specific conditions; to move it closer to the agencies of performance is to lose touch with the general plan. As organizations grow, one function after another should take its departure from headquarters and pass down the line of administration, drawn to lower levels, by the necessity of keeping in touch with local conditions.

The definition of what constitutes detail for an officer, in a growing organization, expands. Headquarters gradually change from a directing into a coordinating agency. From the point of view of a superior officer, this sifting of everything to its proper level is the problem of the subordination of detail. It is the onset of the CEO disease. The man of capacity often errs by working with energy rather than intelligence; not seeing that efficiency does not mean alone to do a great deal, and do it well, but also to be constantly engaged upon tasks of one’s caliber. It is undoubtedly a fact that most organizations are in a state of being strangled by undue concentration of work at headquarters, while the subordinate ranks are soldiering. The proper place for deliberation, and even leisure, is where the far-reaching decisions are being made.

From the point of view of the minor official, the proper division of administrative functions means dignifying him in the eyes of those over whom he is set. Well scattered responsibility sobers and settles a force of executives, and develops and seasons their talents; for individual character is not developed by imagining responsibility, but by actually carrying it. The progress of an organization is largely due to the ambitious upward pressure of the ranks below. Judicious liberty will increase this pressure, and form a prime means of insuring the future.

A visit to the Tabor Manufacturing Co., the Link-Belt Co., and the J. M. Dodge Co. will convince anyone who looks the employees over, finds that the men are happier, healthier, better paid, and in better condition in every way than the men found in similar work in that vicinity. These places above named are among the shops where Scientific Management in its highest form has been in operation the longest time. Frank Galbraith (1907)

Directly or indirectly the instincts are the prime movers of all human activity; by the conative or impulsive force of some instinct (or of some habit derived from an instinct), every train of thought, however cold and passionless it may seem, is borne along toward its end, and every bodily activity is initiated and sustained. The instinctive impulses determine the ends of all activities and supply the driving power by which all mental activities are sustained; and all the complex intellectual apparatus of the most highly developed mind is but a means toward these ends, is but the instrument by which these impulses seek their satisfactions, while pleasure and pain do but serve to guide them in their choice of the means.

Take away these instinctive dispositions with their powerful impulses, and the organism would become incapable of activity of any kind; it would lie inert and motionless like a wonderful clockwork whose main-spring had been removed or a steam engine whose fires had been drawn. These impulses are the mental forces that maintain and shape all the life of individuals and societies, and in them we are confronted with the central mystery of life and mind and will.

In man, instinct is more universal and more powerful than reason; indeed, reason plays a relatively small part in the lives and activities of most men. The contrary opinion is due to our inveterate habit of acting instinctively and then attempting to explain to ourselves or to others the reason for the act. Indeed, mankind, as a whole, has but recently begun to emerge from a life of instinct to one of intelligence and reason. Some races and some individuals have gone farther in this direction than others, but with the great mass of mankind instinct is still the guide of life.

The principal instincts of all animals are those which concern safety, food, and reproduction; the most important social instincts have to do with the defense, welfare, and perpetuity of the group.

In addition to the general instincts the following more special ones have served to bind the higher mammals together in societies:

- The instinct of service, especially between members of the same family or social group.

- The fear of isolation or disapproval and the desire for fellowship, or sympathy.

- The tendency to follow trusted leaders, but not to depart too far from precedents.

These are the integrating, coordinating, harmonizing bonds which unite men in societies. They are deep-seated instincts not easily overcome. The presence and power of these instincts in practically all peoples of the earth has been demonstrated in a most remarkable manner during the Great War. It is reassuring to find that the integrative instincts on which society is founded have not disappeared, and while these foundations remain let no one despair of the future of society.

On the other hand, among the higher mammals and especially among men there are disintegrative instincts or desires which tend to disrupt societies or at least to create disharmony. Among these are:

- The desire for individual freedom, even when it conflicts with the welfare of society.

- The tendency to limit social cooperation to groups or classes based upon family, racial, national; temperamental, environmental, industrial, intellectual, or religious homogeneity.

The incompleteness of integration, cooperation, and harmony in human society is due to the fact that imperfect intelligence and freedom have come in to interfere with instinct. Disharmony in ourselves and in society is the price we pay for personal intelligence and freedom. The more intelligence one has the greater is his freedom from purely instinctive responses, but man is never wholly free from the influences of instinct. The personal freedom which endangers human cooperation opens at the same time a path of progress along rational lines. In our individual behavior and in our social activities we now seek the ideal harmony of the hive, but on the higher plane of intelligence, freedom, and ethics.

The past evolution of man has occurred almost entirely without conscious human guidance; but with the appearance of intellect and the capacity of profiting by experience a new and great opportunity and responsibility has been given man of directing rationally and ethically his future evolution. More than anything else, that which distinguishes human society from that of other animals is just this ability, incomplete though it is, to control instincts and emotions by intelligence and reason.

Those who maintain that racial, national, and class antagonisms are inevitable because they are instinctive, and that wars can never cease because man is by nature a fighting animal, really deny that mankind can ever learn by experience; they look backward to the instinctive origins of society and not forward to its rational organization. We shall never cease to have instincts, but, unless they are balanced and controlled by reason, human society will revert to the level of the pack or herd or hive. The foundations of human society are laid in gregarious instincts, but upon these foundations human intelligence has erected that enormous structure which we call civilization. William McDougall (1918)

In recent weeks we have heard much about the efficiency of industrial democracy, of shop committees, of senate and house plans, of collective bargaining, as the panaceas for all labor problems. During the same period, we have had striking examples of the inadequacy of all these plans. Industrial democracy is a misnomer unless fairly and honestly applied. Collective bargaining is a great danger if wrongly applied and used as an instrument of autocratic power.

Labor problems have always existed and are likely to continue. There is no panacea, as industrial democracy, profit sharing, committee system, open shop, closed shop or collective bargaining. None of these agencies will accomplish or avail much unless there be behind them and disseminated through every fibre and thread, the spirit of fairness, honesty and justice. If these principles be present, there will be no labor trouble. And again, if they be present, it does not matter much what plan is used.

This accounts for many striking examples of the successful management of labor through each of the plans named. Because these successful examples can be pointed out is the reason for the confusion in the minds of many-whereas if a close analysis be made, it would be found that the wholesome conditions existing in each case were not due to the plan in vogue, but to the fact that the employer and the employee each, in turn, was a believer in, and a practitioner of, the cardinal virtues of honesty, fairness and justice.

The unfortunate thing is that many employees; many employers; many associations of employers; many labor organizations, have violated and ignored these principles. Through the utter disregard of the principles of honesty, fairness and justice, great damage has been done, and to quote, “Great powers have been used arbitrarily and autocratically, to exact unmerited profit or compensation by both capital and labor. This policy of exacting profit rather than rendering service has wasted enormous stores of human and natural resources, and has put in places of authority those who seek selfish advantage regardless of the interests of the community.”

The problem before the American public is to evolve those plans and to inaugurate those policies that will make such use of arbitrary and autocratic power a grave offense against the community and to make it impossible for any such arbitrary power to invoke its wrath against the will and against the welfare of the masses. Such plans should provide severe and sure punishment for the autocratic employer or autocratic labor leader who willfully violates the principles of honesty, fairness and justice, and by such violations brings hardships, despair and heartaches upon the masses. One is just as guilty as the other and we have had glaring examples of the evils of the financial trust and of the labor trust. Both are equally culpable and both should be dealt with in like manner.

Many of the abuses have grown up through ignorance of cause and effect. Poor management, incompetent supervision, excessive equipment, large inventories, poor equipment, inadequate sales policies and other causes have resulted in reduced income and a loss of net profits. Ignorance of the causes leads to a misinterpretation of the reason for the effects. In arriving at a solution, incompetency in management again shows itself; faulty analysis and incorrect conclusions follow. Wages are cut, demands increased, working conditions made less desirable; all of which is a disregard of the principles of honesty, fairness and justice. The result being strained relationships, strikes, bloodshed, and destruction of property no one permanently benefitted.