Securing a Square Deal

Background

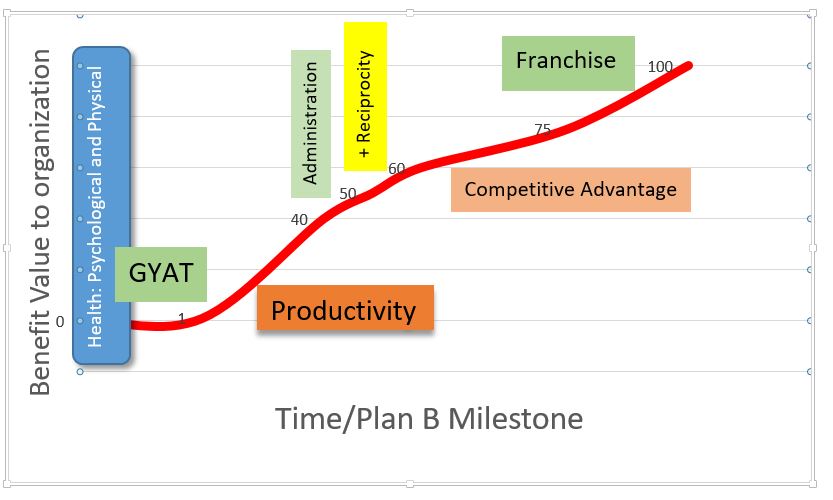

When Plan B becomes operational, performance measurements are taken over time for comparison to the original state-of-affairs benchmarks established at the start. With benefits accumulating on the bottom line, it’s time to take stock of what the keystones and their revenue crews have attained compared to the size of the investment and the consequences generated by the inherited dysfunctional system. The payoffs to the organization are direct to the bottom line. Because upfront costs are so small, the ROI is astronomical.

About the time the Plan B payoffs are appearing in the treasury, the instinct of fairness in each contributor to Plan B rightfully asks, “What about the people who overwrote Plan A with Plan B that created the windfall appearing in the organization’s bank account?”

Wide experience with Plan B taught us a painful lesson – that the people instrumental to plan B success will not get a square deal from the host hierarchy. By now, you should be able to enumerate the reasons for that oversight for yourself. It’s built-into every head-shed groupthink. The lack of fairness by corporate management regarding their workforce has a long history. It is a marker of Achievemephobia, a common psychological malady, sister to the Imposter Syndrome, and the majority of the upper hierarchy have both. It is unrealistic to expect the head shed to break ranks on its groupthink doctrines and fairly share the windfall it did nothing to create. This reality collides with the fact the concept of a square deal is built-in to our subconscious minds. That means the factors of a square deal are taken into account by the workforce without cognitive effort instantly. It is amazing how close people’s measure of square deal aligns with each other.

The instinct of fair play must be accommodated constantly or Plan B viability cannot long be maintained. Accordingly, the architects of the plan B windfall know they have to arrange for equitable allocation of the windfall proceeds themselves. Because the host management will keep the profits, if it doesn’t want a return to Plan A conditions, it must cooperate with the workforce licensing strategy. There is an established commercial device for doing exactly this, the franchise.

Workforce oppression

Abuse of the workforce dates back to the advent of the industrial revolution. Manifestation of the instinct of the ruling class to abuse those who produce what they consume goes back millennia. A century ago, H.S. Dennison discussed the subject. Even though nothing has changed, any discussion of fairness must begin with the existing incoherence of tall hierarchical organizations.

“In a region or in a trade where oppressive measures of employers towards workers have been the rule, not even the most perfect handling of labor problems by one concern can yield full fruit. Under such circumstances, a concern must not only understand the limitations under which it works, but may have to take active steps to remove or reduce these limitations.

Of late years the thought has been making headway that centralizing great masses of workers into a single manufacturing plant has evils as well as advantages, and that at some point of such concentration the evils can be expected to outweigh the advantages.

More than one company, made up of a combination of smaller factories, has found some of its branches operating in semirural towns to have made records of efficiency which their larger plants cannot equal. This problem of the limits of effective concentration offers itself to every growing organization. A part of the economic justification for pensioning retired workers arises from the fact that a community ill-will inevitably results if old employees are laid off under conditions which subject them to serious hardship.

The necessity for the payment of pensions to employees retired after long service arises out of the imperfections of human nature. A man reasonably paid and perfect in foresight would, barring calamities, need no pension.

Employers perfect in knowledge of their own broad self-interest would not pay rates unreasonably low. But no such perfections exist and old employees, sometimes without other resources than their wages, must be discharged if the organization is not to stumble over its own members. To “turn out such men to starve” may be “fair” or “unfair” —who can know—but it is certain that it creates an active ill-will among the remaining employees and in the community.

For if for any reason a mill gets a bad name, every man and woman in its community is restrained from giving full service, and every incentive to work is weakened by the effects of home, club, or lodge opinion. To keep an organization vigorous and healthy throughout and yet to avoid the costs of ill-will caused by casting off the members who have had to ease up in their share of work, proper pension payments seem to have become an economic necessity.

Since the total strength of an organization can be no greater than the aggregate powers of its members, it is important for organization engineering to consider the physical condition and well-being of each member. This fact was first given its fullest recognition by armies, where its bearing is most obvious. Under military influence a few states have undertaken definite measures towards public health; and since the World War there seem to be signs that such activities are on the increase. Especially has it become clear of late years that the effectiveness of public-school and collegiate teaching is dependent to a considerable degree upon the health of the pupils.

Business organizations in the United States began some thirty years ago to face their more obvious health problems such as disability through accident, sickness, and bodily defects. The extension of the work has been rapid, until today a very large number of employees are given some degree of medical service. Intensive progress has been much slower. Health work can be rather sharply divided into the curative and the preventive. The latter, like a capital investment, is slower in its effects and more difficult to plan soundly; but is more fundamental and far reaching.

In neither business organizations nor society at large has it yet taken more than a few first steps. Its opportunities seem very great. One medical problem worthy of intensive study is what length of the working day is best for health and efficiency. Obviously, this best length is not absolute but relative— not merely physiological, but also psychological. Where there is a live interest in the work, eight hours may be too little; where any interest is impossible, it may be too much.

There is little cogency in the old-fashioned argument of the corporation official that nine hours is certainly none too much for the laborers if he, himself, can work ten or a dozen without harm. The best length is relative to working strains of many sorts, and to the distribution of working periods. Eight hours’ work spread over thirteen hours of required attendance has effects different from eight in ten. Rest and relief periods greatly affect the “best length.” They have still been too little studied and experimented with, for they hold a key to many problems of fatigue, monotony, nerve wrack, pessimism, and blind strife.

Monotony is a major problem of organization engineering in its broadest sense—not of industry alone. It is a resultant of the job plus the worker, not of the job alone. And fatigue, worry, and annoyance may be too easily mistaken for monotony at serious risk of applying aggravations in attempting cures. It is because the character of leisure affects work, and the conditions of work affect leisure, that the social problems of the mechanization of industry cannot be regarded as fully solved by the mere reduction of hours. It is by no means certain whether men rigidly serialized for even four hours a day would seek upbuilding or whether they would seek benumbing activities in their free hours.

It is a fair inference that the less uplifting the job, the less uplifting will be the choice of leisure activities. Upon the managers and non-mechanized employees the effects of short work and long leisure must also be estimated. The race of man has not had much experience with widespread prosperous leisure, and what it has had is not favorable enough to warrant a comfortable complacency.

While it is wholly probable that better methods in general education, keeping pace with the necessarily slow increase in the extent of leisure, will lead in a wholesome direction, industrial managers cannot as yet feel free from the responsibility of so arranging the working job itself that it will hold the worker’s interest to the highest degree possible.

The physical and nervous condition of members of an organization affects not only their own work, it affects their attitude toward each other and hence, to some degree, has an influence upon the work of all. It certainly affects their attitude towards management; and so from several directions helps to raise or lower the morale of the whole organization. It is this varied and varying membership upon which the influences of an organization must so act that each one will know what he is to do, will want to do it, and will do it.

Success in inspiring energetic action among the individual members of an organization increases the chances of internal frictions, strains, and conflicts. Organization engineering might, in fact, regard its members as individual but interconnected power centers. These separate centers, brought into close contact, set up reactions not unlike the electrical inductions and resistances which make it impossible to throw the energy from each power center, independently of all the others, directly into the main stream. A great variety of devices must be used to minimize or to overcome these adverse reactions.”

Value proposition

Step back and think about what has been achieved in reaching Plan B. The generic process works for all hierarchical organizations. To any Plan A organization you are the flourishing example of Plan B. Think about what you can offer, obtainable nowhere else, at any price. Only you can provide the interventionist for the FLLP and a full rank of veterans to coach the client keystones through the process. There is no risk of process failure and there’s nothing to buy.

A franchise is a business whereby the owner licenses its operations and knowledge in exchange for a financial consideration. The type of franchise involved with Plan B is called “business format.” It licenses an entire way (ideology) of doing business with interventionist expertise to implant and veteran coaching provided by the franchisor after Plan B is operational (entropy extraction). Licensing Plan B’s value proposition is a workable means for the Plan B workforce to compensate itself for its remarkable feat of implanting and maintaining Plan B.

Arranging for the franchise scope and marketing is done by the interventionist, promoters, and keystones in collaboration. There are dozens of ways to position the streaming windfalls and there are many marketing strategies to test. Since there are no precedents for a franchise as dramatic as Plan B, the list of winning strategies will have to be narrowed by the process of elimination. A marketing breakthrough for licensing Plan B will be a monumental event, one beyond developing Plan B itself.

The facts of value surrounding the realization of Plan B are clear. An implementation example of Plan B, a real one you can audit, had 350 employees in an organization with annual revenue of $40M/yr at 5% net profit. After Plan B overwrote Plan A, with the same staff and equipment, net profit steadily rose to 30% of revenue. Check it out.

The value proposition offered in the franchise is beyond dispute. Since the reception of the plan B concept by corporate potentates will be the same as that of franchise home base, marketing the franchise directly to top management is the pursuit of the impossible. The value proposition is not effective with the upper hierarchy. It values social status by authority and entitlement paramount. Management is aggressively uninterested in Plan B. These entitled consumers are plagued by both the Imposter Syndrome and Achievemephobia. Petitioning management for fairness in this matter is a waste of time.

The marketing of Plan be must be in the form of a business proposition with a P&L statement. The franchise vehicle has been formalized and standardized without reference to social system ideologies.

From the FLLP initiative forward, the attainment of Plan B status is 100% a workforce project.

Streaming Windfalls, Directly measurable factors

The delta symbol means difference and the arrows indicate direction of change.

- Productivity ∆↑ 25% (recovering the cost of Ca’canny + innovation)

- Turnover and absenteeism ∆↓ 80%

- Safety: Losses ∆ ↓ 50%

- Damage and waste ∆↓ 50%

- Availability ∆↑

- Health ∆↑

-

- Physical ∆↑

- Mental ∆↑

- Physical ∆↑

-

-

-

- Endocrine system

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Testosterone ∆↓

- Oxytocin surges ∆↑

-

-

-

Indirect-evidence factors

- Quality of goods and services

- Morale

- Inalienable rights restoration

- GIGO reduction

- Managerial, supervisory, and administrative workloads

- Resilience to unforeseen disturbances ∆↑

- Authentic, specified responsibility for goal attainment

- Entropy extraction, maintenance ∆↑

Enabled growth opportunities

- Positive reciprocity

- Competitive advantage

- Franchising/licensing

There are direct financial impacts on the organizational from OD and there are indirect impacts of OD that eventually also show up on the financial statement. All the negative effects result from psychological phenomena. The OD era of plan A is heralded when Ca’canny of the workforce snaps into place.

The direct effect of Ca’canny, a loss in productivity, increases the cost of production by a nominal 25%. The indirect costs of Plan A OD include:

- Turnover, absenteeism

- Workforce security, health and safety

- Psychological

- Physical

- Process availability

- GIGO, opacity. Undetected bad choices

- Customer dissatisfaction

- Stakeholder dissatisfaction

- Administrative overhead

- Inspection

- Policing for corruption

- Regulation

- Litigation

- Insurance

- Public relations

The distinction of Plan A in OD is that all of the added costs, direct and indirect, come out of the net profits of the organization. The full scope of Plan A (OD) costs was first assembled and quantified by comparison to the first Plan B financial statement in 2013, available for independent audit, upon request.

The toll on workforce personnel from OD includes:

- Internal energy loss to angst and insecurity

- Loss in health and safety

- Loss of inalienable rights, fair play

- Loss of self-respect

The impacts on individuals, all measurable, eventually show up on the bottom line (turnover) when the employee leaves.

General remarks

Getting to Plan B productivity is a psychological phenomenon, engineered by the interventionist for the keystones who custom fit Plan B thinking to their workers. There is nothing to buy, nothing to install. The switch from Ca’canny to productive mode is so abrupt it affirms its roots in the subconscious mind, which has no inertia to overcome and makes task-action choices, starting from scratch, in a centisecond.

The foundation of organizational flourishing is productivity. It is 100% a workforce project. When the Business Process Reengineering fad was championed by Hammer and Champy in 1990, it was top-down, where the workforce stood aside while outside engineers installed a new process for it to operate. By 1997 it was clear that BPR had run its course. The rise and fall curve of BPR matched the rise and fall of its predecessor Total Quality Management (TQM), also top-down, which peaked in the 1980s.

The economic view of Plan A serves to quantify its scope and reach. There are direct costs, like productivity, and there are indirect costs, like overhead. Some intangibles, like morale, have real consequences that are difficult to quantify. The good news is that an accounting of just the quantifiable streaming losses in Plan A is more than enough reason to overwrite Plan A with Plan B.

Zero risk value proposition

Absence of risk to the franchisee is a hallmark feature of the franchise. The upfront screening process performed by the interventionist, protects both parties in the license. If the project is going to fail, the interventionist will know it by the second episode of season one. Failure at that point can only be due to violations of the stop rules. That event triggers the provision for compensation in the licensing agreement.

Plan A economics

There are five functional cost centers in the financial breakdown:

- Productivity

- Administration

- Positive reciprocity

- Competitive advantage

- Franchising

Centers 3-5 are uniquely enabled by Plan B

Productivity

The direct effect of Ca’canny, a loss in productivity, increases the cost of production by a nominal 25%. Productivity is defined herein as cost of production minus losses and waste.

Administration

The administrative costs of Plan A OD include:

- Turnover

- Workforce security, health and safety

- Psychological

- Physical

- GIGO, opacity. Undetected bad choices

- Customer dissatisfaction

- Stakeholder dissatisfaction

- Overhead

- Inspection

- Policing for corruption

- Regulation

- Litigation

- Insurance

- Public relations

Keystone Task Sequence

- Form keystone brotherhood

- Clue workers in on strategy. Enjoy benefits other than financial, for now

- Franchise-ready. Offer franchisor status to host management.

- Value proposition, all measurables, adequate

- Immediate

- Projected

Note:

If the business relationship that you are entering into includes (a) the license of a trademark, (b) the payment of a fee, and (c) an agreement where you will have a level of control over how someone operates their business, the business relationship is deemed a franchise and subject to the franchise laws. In the case of licensing Plan B, none of those issues apply. There is no trademark, no upfront fee, and no control.

When clients prove worthy by site visits, licensing lawyers complete the deal. The license includes financial penalties for stop-rule violation.

Views: 128