Report Card

By Harvard Professor J. Sterling Livingston

How effectively a manager will perform on the job cannot be predicted by the number of degrees he holds, the grades he receives in school, or the formal management education programs he attends. Academic achievement is not a valid yardstick to use in measuring managerial potential. Indeed, if academic achievement is equated with success in business, the well-educated manager is a myth.

Managers are not taught in formal education programs what they most need to know to build successful careers in management. Unless they acquire through their own experience the knowledge and skills that are vital to their effectiveness, they are not likely to advance far up the organizational ladder.

Although an implicit objective of all formal management education is to assist managers to learn from their own experience, much management education is, in fact, miseducation because it arrests or distorts the ability of managerial aspirants to grow as they gain experience. Fast learners in the classroom often, therefore, become slow learners in the executive suite.

Men who hold advanced degrees in management are among the most sought after of all university graduates. Measured in terms of starting salaries, they are among the elite. Perhaps no further proof of the value of management education is needed. Being highly educated pays in business, at least initially. But how much formal education contributes to a manager’s effectiveness and to his subsequent career progress is another matter.

Professor Lewis B. Ward of the Harvard Business School has found that the median salaries of graduates of that institution’s MBA program plateau approximately 15 years after they enter business and, on the average, do not increase significantly thereafter. While the incomes of a few MBA degree holders continue to rise dramatically, the career growth of most of them levels off just at the time men who are destined for top management typically show their greatest rate of advancement.

Equally revealing is the finding that men who attend Harvard’s Advanced Management Program (AMP) after having had approximately 15 years of business experience, but who—for the most part—have had no formal education in management, earn almost a third more, on the average, than men who hold MBA degrees from Harvard and other leading business schools.

Thus the arrested career progress of MBA degree holders strongly suggests that men who get to the top in management have developed skills that are not taught in formal management education programs and may be difficult for many highly educated men to learn on the job.

Many business organizations are cutting back their expenditures for management training just at the time they most need managers who are able to do those things that will keep them competitive and profitable. But what is taking place is not an irrational exercise in cost reduction; rather, it is belated recognition by top management that formal management training is not paying off in improved performance.

If the current economy wave prompts more chief executives to insist that management training programs result in measurable improvement in performance, it will mark the beginning of the end for many of the programs which industry has supported so lavishly in the past. As Marvin Bower has observed:

One management fad of the past decade has been management development. Enormous numbers of words and dollars have been lavished on this activity. My observations convince me that, apart from alerting managers more fully to the need for management development, these expenditures have not been very productive.

Unreliable Yardsticks

Lack of correlation between scholastic standing and success in business may be surprising to those who place a premium on academic achievement. But grades in neither undergraduate nor graduate school predict how well an individual will perform in management.

After studying the career records of nearly 1,000 graduates of the Harvard Business School, for example, Professor Gordon L. Marshall concluded that “academic success and business achievement have relatively little association with each other.” In reaching this conclusion, he sought without success to find a correlation between grades and such measures of achievement as title, salary, and a person’s own satisfaction with his career progress. (Only in the case of grades in elective courses was a significant correlation found.)

Clearly, what a student learns about management in graduate school, as measured by the grades he receives, does not equip him to build a successful career in business.

Scholastic standing in undergraduate school is an equally unreliable guide to an individual’s management potential. Professor Eugene E. Jennings of the University of Michigan has conducted research which shows that “the routes to the top are apt to hold just as many or more men who graduated below the highest one third of their college class than above (on a per capita basis).”

A great many executives who mistakenly believe that grades are a valid measure of leadership potential have expressed concern over the fact that fewer and fewer of those “top-third” graduates from the better-known colleges and universities are embarking on careers in business. What these executives do not recognize, however, is that academic ability does not assure that an individual will be able to learn what he needs to know to build a career in fields that involve leading, changing, developing, or working with people.

Overreliance on scholastic learning ability undoubtedly has caused leading universities and business organizations to reject a high percentage of those who have had the greatest potential for creativity and growth in nonacademic careers.

This probability is underscored by an informal study conducted in 1958 by W.B. Bender, Dean of Admissions at Harvard College. He first selected the names of 50 graduates of the Harvard class of 1928 who had been nominated for signal honors because of their outstanding accomplishments in their chosen careers. Then he examined the credentials they presented to Harvard College at the time of their admission. He found that if the admission standards used in 1958 had been in effect in 1928, two thirds of these men would have been turned down. (The proportion who would have been turned down under today’s standards would have been even higher.)

In questioning the wisdom of the increased emphasis placed on scholastic standing and intelligence test scores,

Dean Bender asked, “Do we really know what we are doing?”

There seems to be little room for doubt that business schools and business organizations which rely on scholastic standing, intelligence test scores, and grades as measures of managerial potential are using unreliable yardsticks.

Career Consequences

False notions about academic achievement have led a number of industrial companies to adopt recruiting and development practices that have aggravated the growing rates of attrition among bright and young managerial personnel. The “High Risk, High Reward” program offered by a large electrical manufacturer to outstanding college graduates who were looking for challenging work right at the beginning of their careers illustrates the consequences of programs that assume that academic excellence is a valid yardstick for use in measuring management potential:

Under this company’s program, high-ranking college graduates were given the opportunity to perform managerial work with the assistance of supervisors who were specially selected and trained to assess their development and performance. College graduates participating in the program were assured of promotion at twice the normal rate, provided they performed successfully during their first two years. Since they were to be “terminated” if they failed to qualify for promotion, the program carried high risks for those who participated.

The company undertook this High Risk, High Reward program for two reasons: (1) because its executives believed that ability demonstrated by academic achievement could be transferred to achievement in the business environment, and (2) because they wished to provide an appropriate challenge to outstanding college graduates, particularly since many management experts had contended that “lack of challenge” was a major cause of turnover among promising young managers and professionals.

The candidates for the program had to have a record of significant accomplishment in extracurricular activities, in addition to a high order of scholarship, and had to be primarily interested in becoming managers. Young men were recruited from a cross section of leading colleges and universities throughout the nation.

Although they were closely supervised by managers who had volunteered to assist in their development, at the end of five years 67% had either terminated voluntarily or had been terminated from their jobs because they had failed to perform up to expectations and were judged not capable of meeting the program’s objectives. This rate of attrition was considerably higher than the company had experienced among graduates with less outstanding academic records.

Arrested progress & turnover:

Belief in the myth of the well-educated manager has caused many employers to have unrealistic performance expectations of university graduates and has led many employees with outstanding scholastic records to overestimate the value of their formal education. As a consequence, men who hold degrees in business administration—especially those with advanced degrees in management—have found it surprisingly difficult to make the transition from academic to business life. An increasing number of them have failed to perform up to expectations and have not progressed at the rate they expected.

The end result is that turnover among them has been increasing for two decades as more and more of them have been changing employers in search of a job they hope they “can make a career of.” And it is revealing that turnover rates among men with advanced degrees from the leading schools of management appear to be among the highest in industry.

As Professor Edgar H. Schein of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management reports, the attrition “rate among highly educated men and women runs higher, on the average, than among blue-collar workers hired out of the hard-core unemployed. The rate may be highest among people coming out of the better-known schools.” Thus over half the graduates of MIT’s master’s program in management change jobs in the first three years, Schein further reports, and “by the fifth year, 73% have moved on at least once and some are on their third and fourth jobs.”

Personnel records of a sample of large companies I have studied similarly revealed that turnover among men holding master’s degrees in management from well-known schools was over 50% in the first five years of employment, a rate of attrition that was among the highest of any group of employees in the companies surveyed.

The much publicized notion that the young “mobile managers” who move from company to company are an exceptionally able breed of new executives and that “job-hopping has become a badge of competence” is highly misleading. While a small percentage of those who change employers are competent managers, most of the men who leave their jobs have mediocre to poor records of performance. They leave not so much because the grass is greener on the other side of the fence, but because it definitely is brown on their side. My research indicates that most of them quit either because their career progress has not met their expectations or because their opportunities for promotion are not promising.

In studying the career progress of young management-level employees of an operating company of the American Telephone & Telegraph Company, Professors David E. Berlew and Douglas T. Hall of MIT found that “men who consistently fail to meet company expectations are more likely to leave the organization than are those who turn in stronger performances.”

I have reached a similar conclusion after studying attrition among recent management graduates employed in several large industrial companies. Disappointing performance appraisals by superiors is the main reason why young men change employers.

“One myth,” explains Schein, “is that the graduate leaves his first company merely for a higher salary. But the MIT data indicate that those who have moved on do not earn more than those who have stayed put.” Surveys of reunion classes at the Harvard Business School similarly indicate that men who stay with their first employer generally earn more than those who change jobs. Job-hopping is not an easy road to high income; rather, it usually is a sign of arrested career progress, often because of mediocre or poor performance on the job.

What Managers Must Learn

One reason why highly educated men fail to build successful careers in management is that they do not learn from their formal education what they need to know to perform their jobs effectively. In fact, the tasks that are the most important in getting results usually are left to be learned on the job, where few managers ever master them simply because no one teaches them how.

Formal management education programs typically emphasize the development of problem-solving and decision-making skills, for instance, but give little attention to the development of skills required to find the problems that need to be solved, to plan for the attainment of desired results, or to carry out operating plans once they are made. Success in real life depends on how well a person is able to find and exploit the opportunities that are available to him, and, at the same time, discover and deal with potential serious problems before they become critical.

Problem Solving

Preoccupation with problem solving and decision making in formal management education programs tends to distort managerial growth because it overdevelops an individual’s analytical ability, but leaves his ability to take action and to get things done underdeveloped. The behavior required to solve problems that already have been discovered and to make decisions based on facts gathered by someone else is quite different from that required to perform other functions of management.

On the one hand, problem solving and decision making in the classroom require what psychologists call “respondent behavior.” It is this type of behavior that enables a person to get high grades on examinations, even though he may never use in later life what he has learned in school.

On the other hand, success and fulfillment in work demand a different kind of behavior which psychologists have labeled “operant behavior.” Finding problems and opportunities, initiating action, and following through to attain desired results require the exercise of operant behavior, which is neither measured by examinations nor developed by discussing in the classroom what someone else should do. Operant behavior can be developed only by doing what needs to be done.

Instruction in problem solving and decision making all too often leads to “analysis paralysis” because managerial aspirants are required only to explain and defend their reasoning, not to carry out their decisions or even to plan realistically for their implementation. Problem solving in the classroom often is dealt with, moreover, as an entirely rational process, which, of course, it hardly ever is.

As Professor Harry Levinson of the Harvard Business School points out:

The greatest difficulty people have in solving problems is the fact that emotion makes it hard for them to see and deal with their problems objectively.

Rarely do managers learn in formal education programs how to maintain an appropriate psychological distance from their problems so that their judgments are not clouded by their emotions. Management graduates, as a consequence, suffer their worst trauma in business when they discover that rational solutions to problems are not enough; they must also somehow cope with human emotions in order to get results.

Problem Finding

The shortcomings of instruction in problem solving, while important, are not as significant as the failure to teach problem finding. As the research of Norman H. Mackworth of the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research, University of California, has revealed “the distinction between the problem-solver and the problem finder is vital.”

Problem finding, Mackworth points out, is more important than problem solving and involves cognitive processes that are very different from problem solving and much more complex. The most gifted problem finders, he has discovered, rarely have outstanding scholastic records, and those who do excel academically rarely are the most effective problem finders.

The importance of a manager’s ability to find problems that need to be solved before it is too late is illustrated by the unexpected decline in profits of a number of multimarket companies in 1968 and 1969. The sharp drop in the earnings of one of these companies—Litton Industries—was caused, its chief executive explained, by earlier management deficiencies arising from the failure of those responsible to foresee problems that arose from changes in products, prices, and methods of doing business.

Managers need to be able not only to analyze data in financial statements and written reports, but also to scan the business environment for less concrete clues that a problem exists. They must be able to “read” meaning into changes in methods of doing business and into the actions of customers and competitors which may not show up in operating statements for months or even for years.

But the skill they need cannot be developed merely by analyzing problems discovered by someone else; rather, it must be acquired by observing firsthand what is taking place in business. While the analytical skills needed for problem solving are important, more crucial to managerial success are the perceptual skills needed to identify problems long before evidence of them can be found by even the most advanced management information system. Since these perceptual skills are extremely difficult to develop in the classroom, they are now largely left to be developed on the job.

Opportunity Finding

A manager’s problem-finding ability is exceeded in importance only by his opportunity-finding ability. Results in business, Peter F. Drucker reminds us, are obtained by exploiting opportunities, not by solving problems. Here is how he puts it:

All one can hope to get by solving a problem is to restore normality. All one can hope, at best, is to eliminate a restriction on the capacity of the business to obtain results. The results themselves must come from the exploitation of opportunities…‘Maximization of opportunities’ is a meaningful, indeed a precise, definition of the entrepreneurial job. It implies that effectiveness rather than efficiency is essential in business. The pertinent question is not how to do things right, but how to find the right things to do, and to concentrate resources and efforts on them.

Managers who lack the skill needed to find those opportunities that will yield the greatest results, not uncommonly spend their time doing the wrong things. But opportunity-finding skill, like problem-finding skill, must be acquired through direct personal experience on the job.

This is not to say that the techniques of opportunity finding and problem finding cannot be taught in formal management education programs, even though they rarely are. But the behavior required to use these techniques successfully can be developed only through actual practice.

A manager cannot learn how to find opportunities or problems without doing it. The doing is essential to the learning. Lectures, case discussions, or text books alone are of limited value in developing ability to find opportunities and problems. Guided practice in finding them in real business situations is the only method that will make a manager skillful in identifying the right things to do.

Natural Management Style

Opportunities are not exploited and problems are not solved, however, until someone takes action and gets the desired results. Managers who are unable to produce effective results on the job invariably fail to build successful careers. But they cannot learn what they most need to know either by studying modern management theories or by discussing in the classroom what someone else should do to get results.

Management is a highly individualized art. What style works well for one manager in a particular situation may not produce the desired results for another manager in a similar situation, or even for the same manager in a different situation. There is no one best way for all managers to manage in all situations. Every manager must discover for himself, therefore, what works and what does not work for him in different situations. He cannot become effective merely by adopting the practices or the managerial style of someone else. He must develop his own natural style and follow practices that are consistent with his own personality.

What all managers need to learn is that to be successful they must manage in a way that is consistent with their unique personalities. When a manager “behaves in ways which do not fit his personality,” as Rensis Likert’s managerial research has shown, “his behavior is apt to communicate to his subordinates something quite different from what he intends. Subordinates usually view such behavior with suspicion and distrust.”

Managers who adopt artificial styles or follow practices that are not consistent with their own personalities are likely not only to be distrusted, but also to be ineffective. It is the men who display the “greatest individuality in managerial behavior,” as Edwin E. Ghiselli’s studies of managerial talent show, who in general are the ones “judged to be best managers.”

Managers rarely are taught how to manage in ways that are consistent with their own personalities. In many formal education and training programs, they are in fact taught that they must follow a prescribed set of practices and adopt either a “consultative” or “participative” style in order to get the “highest productivity, lowest costs, and best performance.”

The effectiveness of managers whose personalities do not fit these styles often is impaired and their development arrested. Those who adopt artificial styles typically are seen as counterfeit managers who lack individuality and natural styles of their own.

Managers who are taught by the case method of instruction learn that there is no one best way to manage and no one managerial style that is infallible. But unlike students of medicine, students of management rarely are exposed to “real” people or to “live” cases in programs conducted either in universities or in industry.

They study written case histories that describe problems or opportunities discovered by someone else, which they discuss, but do nothing about. What they learn about supervising other people is largely secondhand. Their knowledge is derived from the discussion of what someone else should do about the human problems of “paper people” whose emotional reactions, motives, and behavior have been described for them by scholars who may have observed and advised managers, but who usually have never taken responsibility for getting results in a business organization.

Since taking action and accepting responsibility for the consequences are not a part of their formal training, they neither discover for themselves what does—and what does not—work in practice nor develop a natural managerial style that is consistent with their own unique personalities. Managers cannot discover what practices are effective for them until they are in a position to decide for themselves what needs to be done in a specific situation, and to take responsibility both for getting it done and for the consequences of their actions.

Elton Mayo, whose thinking has had a profound impact on what managers are taught but not on how they are taught, observed a quarter of a century ago that studies in the social sciences do not develop any “skill that is directly useful in human situations.” He added that he did not believe a useful skill could be developed until a person takes “responsibility for what happens in particular human situations—individual or group. A good bridge player does not merely conduct post mortem discussions of the play in a hand of contract; he takes responsibility for playing it.”

Experience is the key to the practitioner’s skill. And until a manager learns from his own firsthand experience on the job how to take action and how to gain the willing cooperation of others in achieving desired results, he is not likely to advance very far up the managerial ladder.

Needed Characteristics

Although there are no born natural leaders, relatively few men ever develop into effective managers or executives. Most, in fact, fail to learn even from their own experience what they need to know to manage other people successfully. What, then, are the characteristics of men who learn to manage effectively?

The answer to that question consists of three ingredients:

- The need to manage

- The need for power

- The capacity for empathy.

The Need to Manage

This first part of the answer to the question is deceptively simple: only those men who have a strong desire to influence the performance of others and who get genuine satisfaction from doing so can learn to manage effectively. No man is likely to learn how unless he really wants to take responsibility for the productivity of others, and enjoys developing and stimulating them to achieve better results.

Many men who aspire to high-level managerial positions are not motivated to manage. They are motivated to earn high salaries and to attain high status, but they are not motivated to get effective results through others. They expect to gain great satisfaction from the income and prestige associated with executive positions in important enterprises, but they do not expect to gain much satisfaction from the achievements of their subordinates. Although their aspirations are high, their motivation to supervise other people is low.

A major reason why highly educated and ambitious men do not learn how to develop successful managerial careers is that they lack the “will to manage.” The “way to manage,” as Marvin Bower has observed, usually can be found if there is the “will to manage.” But if a person lacks the desire, he “will not devote the time, energy and thought required to find the way to manage.”

No one is likely to sustain for long the effort required to get high productivity from others unless he has a strong psychological need to influence their performance. The need to manage is a crucial factor, therefore, in determining whether a person will learn and apply in practice what is necessary to get effective results on the job.

High grades in school and outstanding performance as an accountant, an engineer, or a salesman reveal how able and willing a person is to perform tasks he has been assigned. But an outstanding record as an individual performer does not indicate whether that person is able or willing to get other people to excel at the same tasks. Outstanding scholars often make poor teachers, excellent engineers often are unable to supervise the work of other engineers, and successful salesmen often are ineffective sales managers.

Indeed, men who are outstanding individual performers not uncommonly become “do-it-yourself” managers. Although they are able and willing to do the job themselves, they lack the motivation and temperament to get it done by others. They may excel as individual performers and may even have good records as first-line managers. But they rarely advance far up the organizational hierarchy because, no matter how hard they try, they cannot make up through their own efforts for mediocre or poor performance by large numbers of subordinates.

Universities and business organizations that select managerial candidates on the basis of their records as individual performers often pick the wrong men to develop as managers. These men may get satisfaction from their own outstanding performance, but unless they are able to improve the productivity of other people, they are not likely to become successful managers.

Fewer and fewer men who hold advanced degrees in management want to take responsibility for getting results through others. More and more of them are attracted to jobs that permit them to act in the detached role of the consultant or specialized expert, a role described by John W. Gardner as the one preferred increasingly by university graduates.

This preference is illustrated by the fact that although the primary objective of the Harvard Business School is to develop managers, less than one third of that institution’s graduates actually take first-line management jobs. Two thirds of them start their careers in staff or specialized non-managerial positions. In the three-year period of 1967, 1968, and 1969, approximately 10% of the graduates of the Harvard Business School took jobs with management consulting firms and the management service divisions of public accounting firms. A decade earlier, in the three-year period of 1957, 1958, and 1959, only 3% became consultants.

As Charlie Brown prophetically observed in a “Peanuts” cartoon strip in which he is standing on the pitcher’s mound surrounded by his players, all of whom are telling him what to do at a critical point in a baseball game: “The world is filled with people who are anxious to act in an advisory capacity.” Educational institutions are turning out scholars, scientists, and experts who are anxious to act as advisers, but they are producing few men who are eager to lead or take responsibility for the performance of others.

Most management graduates prefer staff positions in headquarters to line positions in the field or factory. More and more of them want jobs that will enable them to use their analytical ability rather than their supervisory ability. Fewer and fewer are willing to make the sacrifices required to learn management from the bottom up; increasingly, they hope to step in at the top from positions where they observe, analyze, and advise but do not have personal responsibility for results. Their aspirations are high, but their need to take responsibility for the productivity of other people is low.

The tendency for men who hold advanced degrees in management to take staff jobs and to stay in these positions too long makes it difficult for them to develop the supervisory skills they need to advance within their companies. Men who fail to gain direct experience as line managers in the first few years of their careers commonly do not acquire the capabilities they need to manage other managers and to sustain their upward progress past middle age.

“A man who performs non-managerial tasks five years or more,” as Jennings discovered, “has a decidedly greater improbability of becoming a high wage earner. High salaries are being paid to manage managers.” This may well explain in part why the median salaries of Harvard Business School graduates plateau just at the time they might be expected to move up into the ranks of top management.

The Need for Power

Psychologists once believed that the motive that caused men to strive to attain high-level managerial positions was the “need for achievement.” But now they believe it is the “need for power,” which is the second part of the answer to the question: What are the characteristics of men who learn to manage effectively?

A study of the career progress of members of the classes of 1954 and 1955 at the Graduate School of Industrial Management at Carnegie Institute of Technology showed that the need for achievement did not predict anything about their subsequent progress in management. As Harvard Professor David C. McClelland, who has been responsible for much of the research on achievement motivation, recently remarked:

It is fairly clear that a high need to achieve does not equip a man to deal effectively with managing human relationships…

Since managers are primarily concerned with influencing others, it seems obvious that they should be characterized by a high need for power and that by studying the power motive we could learn something about the way effective managerial leaders work.

Power seekers can be counted on to strive hard to reach positions where they can exercise authority over large numbers of people. Individual performers who lack this drive are not likely to act in ways that will enable them to advance far up the managerial ladder. They usually scorn company politics and devote their energies to other types of activities that are more satisfying to them. But, to prevail in the competitive struggle to attain and hold high-level positions in management, a person’s desire for prestige and high income must be reinforced by the satisfaction he gets or expects to get from exercising the power and authority of a high office.

The competitive battle to advance within an organization, as Levinson points out, is much like playing “King of the Hill.” Unless a person enjoys playing that game, he is likely to tire of it and give up the struggle for control of the top of the hill. The power game is a part of management, and it is played best by those who enjoy it most.

The power drive that carries men to the top also accounts for their tendency to use authoritative rather than consultative or participative methods of management. But to expect otherwise is not realistic. Few men who strive hard to gain and hold positions of power can be expected to be permissive, particularly if their authority is challenged.

Since their satisfaction comes from the exercise of authority, they are not likely to share much of it with lower-level managers who eventually will replace them, even though most high-level executives try diligently to avoid the appearance of being authoritarian. It is equally natural for ambitious lower-level managers who have a high need for power themselves to believe that better results would be achieved if top management shared more authority with them, even though they, in turn, do not share much of it with their subordinates.

One of the least rational acts of business organizations is that of hiring managers who have a high need to exercise authority, and then teaching them that authoritative methods are wrong and that they should be consultative or participative. It is a serious mistake to teach managers that they should adopt styles that are artificial and inconsistent with their unique personalities. Yet this is precisely what a large number of business organizations are doing; and it explains, in part, why their management development programs are not effective.

What managerial aspirants should be taught is how to exercise their authority in a way that is appropriate to the characteristics of the situation and the people involved. Above all, they need to learn that the real source of their power is their own knowledge and skill, and the strength of their own personalities, not the authority conferred on them by their positions. They need to know that overreliance on the traditional authority of their official positions is likely to be fatal to their career aspirations because the effectiveness of this kind of authority is declining everywhere—in the home, in the church, and in the state as well as in business.

More than authority to hire, promote, and fire is required to get superior results from most subordinates. To be effective, managers must possess the authority that comes with knowledge and skill, and be able to exercise the charismatic authority that is derived from their own personalities.

When they lack the knowledge or skill required to perform the work, they need to know how to share their traditional authority with those who know what has to be done to get results. When they lack the charisma needed to get the willing cooperation of those on whom they depend for performance, they must be able to share their traditional authority with the informal leaders of the group, if any exist.

But when they know what has to be done and have the skill and personality to get it done, they must exercise their traditional authority in whatever way is necessary to get the results they desire. Since a leader cannot avoid the exercise of authority, he must understand the nature and limitations of it, and be able to use it in an appropriate manner. Equally important, he must avoid trying to exercise authority he does not, in fact, possess.

The Capacity for Empathy

Mark Van Doren once observed that an educated man is one “who is able to use the intellect he was born with: the intellect, and whatever else is important.” At the top of the list of “whatever else is important” is the third characteristic necessary in order to manage other people successfully. Namely, it is the capacity for empathy or the ability to cope with the emotional reactions that inevitably occur when people work together in an organization.

Many men who have more than enough abstract intelligence to learn the methods and techniques of management fail because their affinity with other people is almost entirely intellectual or cognitive. They may have “intellectual empathy” but may not be able to sense or identify the unverbalized emotional feelings which strongly influence human behavior. They are emotion-blind just as some men are color-blind.

Such men lack what Norman L. Paul describes as “affective empathy.” And since they cannot recognize unexpressed emotional feelings, they are unable to learn from their own experience how to cope with the emotional reactions that are crucial in gaining the willing cooperation of other people.

Many men who hold advanced degrees in management are emotion-blind. As Schein has found, they often are “mired in the code of rationality” and, as a consequence, “undergo a rude shock” on their first jobs. After interviewing dozens of recent graduates of the Sloan School of Management at MIT, Schein reported that “they talk like logical men who have stumbled into a cell of irrational souls,” and he added:

At an emotional level, ex-students resent the human emotions that make a company untidy… [Few] can accept without pain the reality of the organization’s human side. Most try to wish it away, rather than work in and around it… If a graduate happens to have the capacity to accept, maybe to love, human organization, this gift seems directly related to his potential as a manager or executive.

Whether managers can be taught in the classroom how to cope with human emotions is a moot point. There is little reason to believe that what is now taught in psychology classes, human relations seminars, and sensitivity training programs is of much help to men who are “mired in the code of rationality” and who lack “affective empathy.”

Objective research has shown that efforts to sensitize supervisors to the feelings of others not only often have failed to improve performance, but in some cases have made the situation worse than it was before. Supervisors who are unable “to tune in empathically” on the emotional feelings aroused on the job are not likely to improve their ability to empathize with others in the classroom.

Indeed, extended classroom discussions about what other people should do to cope with emotional situations may well inhibit rather than stimulate the development of the ability of managers to cope with the emotional reactions they experience on the job.

Conclusion

Many highly intelligent and ambitious men are not learning from either their formal education or their own experience what they most need to know to build successful careers in management.

Their failure is due, in part, to the fact that many crucial managerial tasks are not taught in management education programs but are left to be learned on the job, where few managers ever master them because no one teaches them how. It also is due, in part, to the fact that what takes place in the classroom often is miseducation that inhibits their ability to learn from their experience. Commonly, they learn theories of management that cannot be applied successfully in practice, a limitation many of them discover only through the direct experience of becoming a line executive and meeting personally the problems involved.

Some men become confused about the exercise of authority because they are taught only about the traditional authority a manager derives from his official position—a type of authority that is declining in effectiveness everywhere. A great many become inoculated with an “anti-leadership vaccine” that arouses within them intense negative feelings about authoritarian leaders, even though a leader cannot avoid the exercise of authority any more than he can avoid the responsibility for what happens to his organization.

Since these highly educated men do not learn how to exercise authority derived from their own knowledge and skill or from the charisma of their own personalities, more and more of them avoid responsibility for the productivity of others by taking jobs that enable them to act in the detached role of the consultant or specialized expert. Still others impair their effectiveness by adopting artificial managerial styles that are not consistent with their own unique personalities but give them the appearance of being “consultative” or “participative,” an image they believe is helpful to their advancement up the managerial ladder.

Some managers who have the intelligence required to learn what they need to know fail because they lack “whatever else is important,” especially “affective empathy” and the need to develop and stimulate the productivity of other people. But the main reason many highly educated men do not build successful managerial careers is that they are not able to learn from their own firsthand experience what they need to know to gain the willing cooperation of other people. Since they have not learned how to observe their environment firsthand or to assess feedback from their actions, they are poorly prepared to learn and grow as they gain experience.

Alfred North Whitehead once observed:

The secondhandedness of the learned world is the secret of its mediocrity.

Until managerial aspirants are taught to learn from their own firsthand experience, formal management education will remain secondhanded. And its secondhandedness is the real reason why the well-educated manager is a myth.

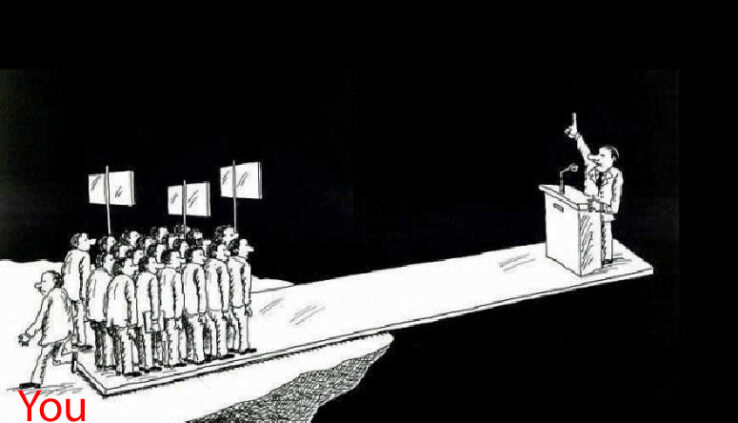

On Management Groupthink

The association of the mentor line with research on forecasting by “experts” has provided an independent look at the groupthink phenomena that truncates understanding social system behavior. The research was simply a compilation of the predictions by top experts v the operational reality. The track record for expert forecasters turned out to be far worse than random chance.

The pattern of behavior when experts were faced with the truth of their forecasts is to explain away their failure and double-down on the validity of their current prediction. Oblivious to the facts, the credentialed experts invariably thought they were doing accurate forecasting. This pattern applied to experts about economic factors and to the experts advising the politicians shaping social affairs. Credentialed experts are ready to fit any sort of information into their world view.

The research included predictions made by non-experts. When open-minded people integrated the offering from several classical disciplines, systems-think, they outperformed the experts in prediction in every measure. Where experts represent narrowness (moreover), system think represents breadth (however). Since society never holds their experts accountable for their predictions, forecasts continue to be worse than useless GIGO. As truth is the heart of learning, embracing the evidence of your forecasts must be fed back to improve your forecasting. No feedback, no chance.

Human nature being invariant, management follows the same scenario exhibited by discipline-centered experts. Because the 2½ rule feeds executives garbage, garbage is used to navigate the Plan A organization. As all social system dysfunctions are driven by a prime mover system residing above the mentor line, it is foolish to expect a Plan A organization, straightjacketed by the mentor line, to remedy itself.

Views: 226