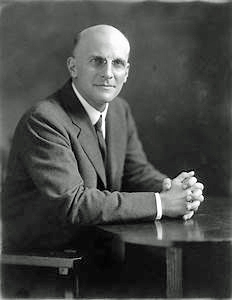

Henry Sturgis Dennison and Plan B

A century ago, on his own, Dennison figured out the pathology of Plan A and many of the essential components of Plan B. He had his own company, Dennison Manufacturing of Framingham, MA to experiment on. He cut a wide swath in high society attempting to bring enlightenment to the Establishment. He didn’t know that to actually attain Plan B status, all the ducks must be lined up. Below are excerpts from his many articles and speeches.

Government regulation and the square deal

In government, holding the right to vote has an influence quite distinct from the influence of the act of voting. To feel that one could have voted, or that one could have spoken in town meeting if one had wished, is to make possible an acceptance of laws or of the acts of officials with slight loss of self-respect.

Where regulations are imposed without representation (and where overwhelming power does not inhibit normal reaction to them), they are more acceptable if imposed by people like one’s own group than by “foreigners.” The regulation of American business by a London Parliament in 1770 seemed oppressive when compared to such regulation by an American Congress; and that now, in its turn, seems oppressive relative to a proposed regulation of one’s own trade association. As trade association regulation shapes itself, it will soon seem oppressive to the minority who will then seek another subdividing process to bring the regulation nearer home.

Trade unions appeal to the desires for self-respect as well as to the economic motives. They afford to their members some participation in fixing the conditions under which they work, and so remove them one step away from the feeling of total subservience. When works councils, representing employees, are genuine, they fill to some degree the same place. The desire for self-expression may be / regarded as implied in the desires for self-respect and social respect. Practically, however, it is worthwhile to consider it separately.

It may itself be subdivided into verbal self-expression and craftsmanship, or expression through activity. To some people the need to talk is really pressing and they could not give their best if so placed in an organization that this need could not occasionally be met. Where there can be pride in work and accomplishment there is an especially strong likelihood that it will need to find part of its expression in telling someone about it. The desire for what one conceives to be justice is interwoven with the desires for self-respect and social respect. The differences in its intensity among men, and especially in more accurate psychological phrase, the self-assertive reaction tendency.

Variety in the kinds of situations men think of as just or unjust, make it peculiarly hard for the organization engineer to take into practical account. Yet, vague as it may be, its influence is too great in crises to allow of its neglect. For this among other reasons it is usually wise to provide that men shall have a chance to understand the purpose of the orders given them. If this chance can be given before the orders are issued, the effects are still better.

In emergencies this is impossible, but in any well-managed organization, the proportion of emergency occasions to total occasions is small. Feelings of resentment and desires for revenge, aroused by what seems an injustice, can exert a strong influence upon men’s actions; so strong indeed in extreme cases as to modify or overcome even the economic motives. This sense of injustice, moreover, may last a long time—longer than any nice calculation of suitability would warrant. But there can be few greater mistakes made in the management of organizations than to act as if resentments did not exist just because they should not. Being feelings, moreover, rather than intellectual reactions, they are relatively immune to logic and argument.

In some cases, they are so firmly held to that men will prefer to suspect the most honest and thoroughgoing measures of alleviation. In general it is true, though by no means always, that resentment and vengeful attitudes against people one seldom sees yield more slowly than against those with whom one is in moderately frequent contact. Between nations, certainly, cherished grudges are reluctantly given up. Wherever it arises within an organization the spirit of resentment is costly and hard to overcome. Great pains are, therefore, well repaid if they can prevent its arising.

Note: The very important field of hierarchical dynamics is only surveyed through the eyes of a layman, but recent experimental psychology has done and is doing much to sharpen and to enrich the understanding of normal feelings of anxiety and inferiority and of common compensation behavior; that is of the normal striving to overcome feelings of inadequacy.

On Trust

No organization can develop loyalty by direct endeavor, but organization may earn loyalty by such practices and attitudes as will allow it to grow naturally. To demand, call for, or even suggest loyalty often works counter to its development, even in a nation, and almost surely in a business organization. If members are to be inspired by the organization itself as well as by its personnel, its purposes and its traditions must be such as will appeal to them. That common purposes and common traditions can be the strongest of bonds and incentives is proven in political communities which have little else to knit them together and yet show a vigorous organized strength.

Naturally, in the larger commercial and industrial organizations, there has so far been little real attempt to make use of this powerful incentive. It is typically the organizations for social service whose objectives have been able to command the enthusiastic efforts of their members. In several government departments the knowledge of the contributions they can make to the common good is a powerful stimulus to employees of all grades.

Of recent years some large corporations have made definite attempts to open the way for a similar response from their employees by extensive advertising of their opportunities and responsibilities for public service. In the last analysis full loyalty must include an adoption and approval of the purpose of the organization to which one is loyal, since that purpose and that only is what gives an organization life, meaning, and significance; is what makes it more than a physical collection of its constituents.

Hence, “my country” (or my company) “right or wrong” is not an expression of loyalty but an announcement of partisanship. Pseudo-loyalties are more than mere harmless imitations. They are actively dangerous because they can so easily mask highly egocentric motives behind the appearance of what is probably the most powerful and, in the end, the loftiest of human impulses.

By nation and church the allegiance of man has often been demanded as a right and sought by force rather than as a studied attempt to enlist wholehearted support. As threats of physical violence have become less predominant in the complex of influences to which men must respond, the truer nature of allegiance and of sovereignty have been more and more the subject of critical study.

There have been many thousands of preachments telling workmen that it is their duty to be loyal to the company they work for. But a man can seldom be furnished actuating motives by telling him he ought to be actuated by them; any favorable response which may follow a preachment is most likely to be the result of motivations running back long before the preachment itself. The only way worth practical consideration is to attempt so to relate the environment to the man that the fullest possible range of desirable motives will operate within him. It is always possible that by preachments, forces actually the opposite of those desired may be set up as defense reactions. Loyalty is likely to be lost rather than gained by demanding or even by asking for it.

Exhortation to good citizenship it useless. We get good citizenship by creating those forms within which good citizenship can operate, by making it possible to acquire the habit of good citizenship by the practice of good citizenship. It is an easy mistake for a business organization to count too heavily upon economic methods of winning loyalty. Disappointment is bound to result when profit sharing or executives’ bonuses are too exclusively relied upon or expected to work beyond their natural powers.

Oftentimes too much has been hoped for from pension and insurance schemes in building up morale and reducing labor turnover; they are, after all, mainly economic influences and react most forcefully upon the self-serving motives. “Chaining by the leg” is no effective way of tying men into an organization, but to own part of the capital assets of an organization—to own land in a country or stock in a company—is an incentive of considerable importance.

Its limitations lie in the fact that it is chiefly economic in nature and, therefore, must act primarily in whatever direction personal advantage runs. Unless strongly supported by a structure of non-financial incentive, economic methods cannot go far in building up loyalty. Loyalty to an organization because it is a source of income—fidelity to a meal ticket—is easy superficially to overrate. There are noisy patriotisms of this sort which do not hesitate to trim their taxes, smuggle, or graft. And where organization bonds are wholly economic, it is impossible to prove logically that grafting is improper. Loyalty at its best is an expression of the desire to expand the “self” to include a wider and wider circle of objects.

The purest and perhaps the commonest expression of loyalty is the ideal family, as has been recognized by those business men who have tried, often inexpertly, to make of their organization “one big family.” But although business as a whole has far to go before so high an ideal comes into sight. Much may be learned of the road by consideration of the fundamentals of family loyalty.

In any case organization engineering can well afford to consider the importance of home influence upon the growth of loyalty. Some companies have already tried a Family Visiting Week, during which wives and mothers can see the work and the work places of their husbands, sons, and daughters; and others have felt it advantageous to include the whole families of employees in their outings or other social gatherings. The loyal impulse, like every other human impulse, must be given exercise if it is to be made use of. It can only find expression in something more than compulsory or pecuniary service.

Two special values, then, lie in the provision by any political organization of plenty of chances for voluntary service. First, that such service gives expression and hence reality and cogency to loyalty; and, second, that as voluntary service becomes more common, the pseudo-loyalties become less able to maintain their deceptions. A democratic nation, particularly, is so deeply dependent upon voluntary service that lack of sufficient provision for it is of especially serious consequence. National loyalty or patriotism can usually be much more easily talked about than proved. Such talk can usually be counted on to call forth prompt applause and is, therefore, often used readily as window dressing or disguise. Naturally in such cases it is especially truculent and noisy.

In any modern community, multiple loyalties are inevitably to be found—to lodge, church, town, union, nation, corporation, family. Business organizations have not yet felt concerned with such multiple loyalties, but political communities and organizations, large and small, must constantly take into account the several allegiances of their members. In few places in this world is there any single and complete sovereignty.

National governments like to be so considered, but they are, nevertheless, limited and conditioned by a considerable variety of traditional privileges and ingrained habits of thought. Whether there is a disposition at all widespread, actively to seek out a cause to which to be loyal may well be the subject of doubt. But the nature of most men is such that when they do find a cause to which they can be loyal, their powers seem to be greatly enhanced.

On goal-setting

As an organization succeeds in impelling its members to greater efforts it finds it more and more important that these efforts should be steered into right directions. If an organization is to be powerful in the pursuit of its purposes each of its members must be stirred to energetic action; but the more active they are, the greater is the danger of disruptions from pulling in all directions. A group of easy-going men is not likely to get much of anywhere but may at least survive, where an aggregation of go-getters risks a breakdown from internal cross-hauling if not strongly directed. At the very beginning of any person’s relationship with an organization, the nature of his place and work in it will have to be made clear.

This means, of course, that someone must know just what it is and how to describe it with definiteness and clarity. The current direction of an organization is the instruction of its members in the individual and departmental tasks into which its work has been subdivided. Upon the basis of a full description of the job there can usually be planned for it a method of training which will help to develop skill in a shorter time, and eventually a higher degree of skill, than a man could ordinarily get if left to himself.

This may seem self-evident; yet it is not often in business organizations that a man is introduced to a new job with anything like an adequate, accurate, and intelligible description of it. The task of explaining is too often left either to those who are too close to the job to see it accurately or to those who have not the ability to describe it clearly. For the more complex positions it is well worth while to have detailed specifications prepared and kept currently revised. Even for the simpler jobs a few experiments will usually prove precise specifications more valuable than had been suspected.

The Army has published complete minimum specifications dividing occupations into what they call “automatisms” and operations that require thinking or exercise of judgement. Not even in the simplest “automatisms” can maximum effectiveness be reached without some sort of training, formal or informal, required or self-imposed.

On training and teaching

Skill is chiefly acquired by developing sets of muscular, ocular, and mental habits so that they work without focusing attention upon them. Even on simple jobs, correct habits can make great differences in production—quantity and quality—and an appropriate training for them may yield a good return upon its cost. The most complicated and exacting jobs demand and repay a well-developed training technique. It is not to be taken for granted that all tasks are to be best learned by starting right in upon them and expecting to gain speed with practice. As with typing and piano playing, it might be that a right course of training would begin with certain muscular motions which are fundamental to future accuracy and speed but are in themselves unproductive.

Especially for that very complex job, managing, it is likely that carefully devised methods of preliminary training are necessary. When a man undertakes the job of foremanship without previous training, as has usually been the practice, pride may force him to cover his ignorance by wrong methods, and these may later grow into fixed habits, impossible wholly to overcome. Much of the swagger and bluster of crude foremanship grew up in this way and became part of the trappings of the trade, accepted without reflection. It must be recognized that the tendency to order men about is not at all uncommon, and that if left to itself it may take very crude forms the value of a specific pre-foreman training which goes beyond class room and book work into actual laboratory practice in being a foreman.

It would put men to work for a few weeks under a variety of foremen whose methods they would analyze and discuss; and would give them practice bossing each other on special jobs and filling in as vacation substitutes. Any organization which means to keep going for more than a short time will have a continuous problem of training; for an organization is an aggregation of the minds of people. Little as each mind may change in a single day, it does change each day— adding to and re-proportioning its stock of thoughts. Each day, also, slowly or quite rapidly, the objectives of any organization change. Hence there is a double need that an organization shall carry along parallel to its daily operating life some sort of regular system of education and reeducation —simple in its provisions if it is to fit relatively simple situations and slow change; more elaborate to fit complex situations and rapid change.

A goodly part of operating management is really teaching. The head of a corporation with, a large force of field salesmen, upon being asked just what measures he used to manage it, found in naming them that everyone was some sort of a teaching device: the announcing of new facts or methods, demonstrating, persuading. But the spirit of this educational project was not that of the old master with his birch and his undebatable dicta; it was always an attempt to carry a true conviction and to train independent thinking.

What was here true in a road-selling department is true in office, store, and factory; real operating management is largely a project in education. Each member of an organization, in addition to a knowledge of his own work, needs to have some degree of knowledge of the purposes and the structure of the whole. The necessary amount will be slight in some positions and considerable in others, but something in practically all works shortly after they are hired, in order to lessen to some extent the vague fears and feelings of uneasiness we all experience in the presence of the strange and unknown, and to increase the chances of their getting the feeling of athomeness.

An English company devotes several days to these trips and to lectures on its structure, markets, methods, and purposes. Current organization education can well be founded upon daily, weekly, or monthly publications. They offer the material upon which an interchange of communication may be begun and a broad community of understanding established. But in few organizations can the written word provide to its members all of the knowledge of its aims and methods which is desirable. Even when talking movies have been fully utilized, there will remain an essential need of personal contact. Assemblies, parliaments, congresses, town meetings have all been powerful educators in the organization of political communities; in industrial organizations, councils and committees are often more valuable as educational than as administrative instruments.

Assemblies and discussion increase knowledge and affect attitudes. Rules for which the reasons are understood, and changes which have been talked over in advance, can expect more effective response than those which are imposed from without. Laws, rules, and regulations may be considered fundamentally as written specifications of the behavior which is currently acceptable or unacceptable to an organization. Obviously the organization must make these known to its members in some way more adequate than through printed circulars or posted notices.

On politics and collaboration

The strongest point to be made in behalf of even such rudimentary political forms as democracy has already attained, popular voting, majority rule, and so on, is that to some extent they involve a consultation and discussion which uncover social needs and troubles. This fact is the great asset on the side of the political ledger . . . Popular government is educative as other modes of political regulation are not.

It forces a recognition that there are common interests, even though the recognition of “why” they are is confined; and the need it enforces of discussion and publicity brings about some clarification of what they are. The ballot is, as often said, a substitute for bullets. But what is more significant is that counting of heads compels prior recourse to methods of discussion, consultation, and persuasion, while the essence of appeal to force, is to cut short resort to such methods. Majority rule, just as majority rule, is as foolish as its critics charge it with being. But it never is merely majority rule.

As a practical politician, Samuel J. Tilden, said a long time ago: “The means by which a majority comes to be a majority is the more important thing.” Every project in education has to adapt itself to the receiving apparatus of its scholars. Information may be accurate and important, but that alone will not make it stick; its form or content must in some way or other make an appeal. The presentation of facts or points of view in a form badly adapted to the hearers may set up in them defenses which will make acceptance forever impossible. The process of imparting information in such a way as to inspire some degree of enthusiasm is the process of gaining conviction. Convinced, persuaded, or, in business slang, “sold,” a man reacts with more of his own energy than when merely “told.” Education has always to take into account the power of the ideas, the assumptions and prejudices acquired early in life.

One day, in a factory which had put in a dozen years of work calculated to build up confidence among its employees, an announcement by the management of an increase in a starting wage was met with almost universal suspicion. The works committee chairman in discussing it called attention to the fact that during his childhood he had continually heard from his father and brothers stories of the tricks and guerrilla warfare between them and their foremen. The habit of suspicion these stories left in his mind could only slowly be displaced. He knew that his own case was similar to that of most of the other older men and women. Only long patience and persistent repetition can be counted upon to overcome any such old-established prejudices. Persuasive repetition is, in fact, an important part of education technique. In campaigns for safety, honesty, waste saving, or care of quality it holds a primary place.

The educative force of example must also be reckoned on in any educational project. Every one’s example is of some effect upon others, especially upon their attitudes. Sincerity and insincerity, conscientiousness and slackness, consideration and ruthlessness, application and laziness spread themselves through an organization slowly, but surely and far.

Any training for the future must take account of the growing complexity of the modern world. A crew able to-day to hold a given place for its organization cannot expect to hold the same relative place ten years hence without a considerable increase in ability. Ward, in his “Dynamics of Sociology,” suggests a law parallel to that of Malthus: While in the progress of civilization the capacity to acquire knowledge increases only in arithmetical or some lower ratio, the amount of knowledge necessary to be acquired increases in a geometrical or some higher ratio.

Feedforward control thinking

An organization which hopes to hold its place over a period of years, and especially if it wants also to grow, will have to undertake definite measures of education to prepare its members for the new complexities of the future. Research, analytical thinking, and broad facilities for training its members to plan ahead will characterize the great majority of the existing organizations which will remain successful twenty years hence. A live organization need not greatly fear that it will fail to tackle those problems which force themselves upon its attention, for sooner or later it must bestir itself, under repeated pressure, for its own comfort.

To go forth, however, to meet its problems first, is quite another matter; then personal comfort counsels neglect and all the inspiration and challenge of clear thinking are needed to counteract its influence. Yet problems met before they meet us are on the whole the easier to solve. Thinking ahead, the careful supposing of cases, the estimating of distant consequences are the sort of theorizing to which we have to bestir ourselves if we want to meet trouble before it meets us, before, in fact, it becomes troublesome trouble. Business concerns have to work upon some theory of the probable trends of change in the markets for the goods they deal in, in the supply of labor and the attitude of workers, and in the chemical or mechanical technique of their processes. If the theory is developed by men of well-digested experience and gifted with imagination, they are fortunate; but only time can disclose such gifts.

Moreover, accuracy of foresight in one set of market conditions or one stage of technical progress may be inaccurate in others, and again only time can actually prove its failure. Experience is an important part of education, but only when put in order and thought over as one would order and think over experiments; bare experience is more likely to unfit than to fit a man to meet changes. Experience as it happens along is usually a slow and expensive means of education. A true system of education is in part a compression of one’s own experience and in part a definite search for a study of the experience of others.

The ideal organization would provide for the greatest possible development of the men within its ranks, and at the same time allow for a proper amount of cross-fertilization by the best of the ideas and abilities it can find outside.

A strict promotion policy of drawing leaders from the ranks obviously has a good influence upon the character and abilities of the whole personnel. It has, however, at least one danger which should definitely be met. This danger resembles somewhat the results of inbreeding; men developed in the ranks may in the long run fail to show as much originality, versatility, and imagination as an organization will need.

An exclusive promotion policy left to itself would probably result in an average board of managers, but only by good fortune would it furnish the one or two men of almost poetic imagination upon which more than average progress depends. It is important, therefore, for any organization to hold itself open to the advantages of getting and assimilating unusual men. If it chooses to operate under a strict promotion policy, it should provide more than the usual opportunities for its own men to get their educations broadened and their imaginations fertilized by outside contacts, by travel, and by reading. To insure itself over the long run an organization will supplement any genius it may find among its membership with such training as will best develop ability to forecast the several most probable trends and to prepare as well as may be to meet them.

Any proper training in the look ahead will make it clear that we can seldom hope to foresee actual situations in detail, but must rather learn to study general trends, and the group of possible and the smaller group of probable situations to which the trends lead. Specific goals, closed systems of the social order, must not be too definitely held before the eyes in thinking out the problems of progress. They are guides to general direction, clarifiers and simplifiers, but not rules of action. To help in the actual steps of progress a healthy and sincere opportunism is absolutely essential. Since future problems can only be partially foreseen, the wisest education for them will consist of practice in analyzing and solving a variety of problems.

Such education should not attempt to stock a complete mental warehouse from which ready-made solutions can be drawn as needed, but should rather try to equip and train a resourceful mental producing department. Education for the future can specifically plan to develop in men and women the habit of looking ahead and of estimating and planning for future contingencies. The cultivation of this habit is not an impossible educational objective. It might even be started in the grade schools, where practice might be given in estimating the probable consequences of simple situations. History so taught would gain much life and interest.

As an educational influence the research division of any organization may be made very valuable. If it is intimately coordinated with the operating departments the organization may gain almost as much from the open-mindedness it induces, as from the more direct results of its studies. Since the future is practically certain to bring about some kind of change, the closed mind runs the greatest risk of being wrong.

It is primarily the experimental attitude and method which have to be cultivated if there is to be a development of the art of management sufficient to meet the growing problems of civilized life. Ideally, an organization would include in its educational schemes its whole membership.

The medical and teaching professions recognize that education must be continuous, extending even to their leaders; and the universities definitely provide for it through the encouragement of research and the institution of the sabbatical year. In corporations the training of district sales managers, salesmen, and foremen is not uncommon and is in some cases carried along elaborately and continuously. These junior officials in fact are, like the non-commissioned officers of an army or the middle classes of a nation, the backbone of an organization, without whose intelligent functioning it cannot realize its full strength.

For an industrial concern it is especially worthwhile to train promising material in advance of promotion. An incidental gain from the more general educational schemes which are meant to give some preparation for promotion arises from the fact that they yield information about men’s qualities which is difficult to get from the results of their daily work. Their influence upon other men, their ability to size up new situations, and their readiness and clarity in expressing themselves are all likely to have new light thrown upon them by the character of the work men do in educational courses.

On the principles of organization

To stimulate men to act with their full powers and to direct their efforts are the daily operating tasks of organization management. But where their numbers begin to be large these men must work within some established arrangement of their mutual relationships which constitute the form or structure of their organization. Just what structure will prove best for any organization depends upon the specific task it is meant to perform, the kind of men it can get, and the particular conditions under which they work.

Even the determination of the ways in which any organization may best be divided into working sections and departments is relative to its own peculiar aims and conditions. Structure is not an 123 end in itself and can do nothing by itself. It can, however, increase or decrease the effectiveness of those who operate under it, and can make the getting and retaining of able men more and less likely.

Principles of organization structure are good only in so far as they help build specific organizations better and more quickly than could be done by trial and error methods. There is nothing sacred in them of themselves. Problems concerning the limits of authority, the field to be covered by rules and laws, the degree of representation and consultation to be provided, the limits of promotion policies and the like, have all to be thought out with reference to particular situations.

There is little to say for or against them in the pure abstract, any more than can be said on such problems as freedom, equality, democracy, and individualism, which cannot be adjudged as good or bad, and can seldom be usefully defined except as applied to some concrete situation.

John Dewey in “The Public and Its Problems” uses this vigorous language: Fraternity, liberty, and equality isolated from communal life are hopeless abstractions. Their separate assertion leads to mushy sentimentalism or else to extravagant and fanatical violence which in the end defeats its own aims.

Equality then becomes a creed of mechanical identity which is false to facts and impossible of realization. Effort to attain it is divisive of the vital bonds which hold men together; as far as it puts forth issue, the outcome is a mediocrity in which good is common only in the sense of being average and vulgar. Liberty is then thought of as independence of social ties, and ends in dissolution and anarchy.

In logic, and usually in fact, problems of organization structure follow after operating problems. Constitution and by-laws may come early, but they are not organization. It is more usual for men to start an enterprise in informal, unorganized fashion and then shape up a structure of organization than to start with the organization first. Sooner or later, however, a structure of organization has got to be so built—and constantly rebuilt—as will best fit the available men into the tasks to be done.

Yet in the very building of it the fact must be borne in mind that just as environment in the organic world affects the organism, so the form of organization under which they work alters men. In the earlier stages, therefore, there will usually be necessary a first approximation to structure into which the imagination can fit the developing personnel and upon which experience will later suggest amendments.

A structural form which is too flatly fitted to present personnel may fail to accomplish the development which a greater amount of pressure and challenge would bring about. Some influences towards leading men on and developing them are not undesirable. Structure must in any case be flexible, not rigid, and specific measures will usually have to be taken to help it remain so; it must strengthen its group, not ossify them.

The living forces of an organization can be kept vital, as Bergson has pointed out, only by counteracting the tendency of every formula to crystallize the living thought that gives it birth; of the idea to be oppressed by the words; and of the spirit to be overwhelmed by the letter. Rules of conduct and methods of organization are instrumental we are obliged to employ, but they are only instruments.

The 2nd Law, omnipotent, omnipresent

The persistent tendency of every organization to institutionalize has been abundantly proved in history. An idea at its birth may be set forth with high spiritual power and significance. To make it effective and to spread it, men form themselves into organizations. Thereafter, in order that the organization may have fuller life, they put the spirit which gave it birth in constant jeopardy.

Industrial organizations are exposed to the same risks of rigidity of structure as they grow in years or in size. A form, adapted to young men of fresher energies, or a simple structure adapted to a small group of men, is easily allowed to crystallize into permanency, insensitive to the gradual changes which have taken place in personnel. Especially liable to a type of rigidity usually called “over-organization” are those combinations and mergers which try to force into a preconceived structure.

An organization must not be built merely to follow a leader; rather, the factors of leadership should be built into the whole structure. For any organization the supreme good fortune is to have a real leader, but organization engineering must take account of the fact that real leadership is extremely scarce and can seldom be specifically planned for. A well-built organization does not attempt to take the place of leadership; it can invite leaders, and if they are found can enhance their power.

Where it happens that the leader comes first, the organization often builds itself around him. It is then most likely to begin its decline when he passes. As the “lengthened shadow of a man” still further lengthens,” it becomes still more shadowy. An institution may be a shadow—an organization must have life of its own. And when it has, it will usually be of more real value to a leader than if it depended wholly upon him for its life.

There are not many organizations which are still alive and of organization-varied groups of living men and women effective organisms whose absolute control has been in one man’s hands for ten or twenty years. Some leaders cultivate yes-men rather than subleaders. It has been said that usually “great men are like great trees: little saplings cannot flourish and grow strong in their vicinity.” Where there is an outstanding leader, therefore, special provisions will have to be made to insure at his passing enough of those factors of leadership without which no organization can live.

Besides the adverse effects which the too-great concentration of power in one man has upon the development of ability and character in an organization, there are the progressive effects of such concentration upon the man himself. Phelps in “Human Nature in the Bible” says: The instance of Napoleon is simply a revelation of human nature; one sees the degeneration of the man steadily and insidiously accompanying the increase in authority . . . Napoleon is so true to form that Emerson took him as the representative of the common man.

There are few indeed who cannot count a half dozen men less notable but nearer home, whose power went to their heads. That any organization should find just the leaders it needs is a matter of chance. But it can be so constructed that men of leadership caliber will feel invited to join and inclined to stay, and can have their caliber discovered. Or an illogical structure can repel the men of leadership quality and miss-educate the others. Chance and luck are facts of life. An organization so constructed that it takes full advantage of all its luck and defends or insures itself against its bad luck, does a good deal to insure its progress.

Since the considerations which govern organization structure are specific and concrete rather than general and abstract, there are definite questions to be answered in each case: What type of work is to be done? What parts will it be cut into and what sort of men will do each.

On concept integration

How to tie the plans together? How to preserve balance and provide for growth and improvement? How to meet emergency? These will be discussed in some detail in what follows.

Before specific questions of form can be answered, it must be known what kind of job the organization is to tackle. Is it to be simple or intricate? Does it call for much originality or little? Will its development be rapid or slow, regular or jumpy? Will its members be in close contact or far flung? For simple jobs the best form is likely to be itself the simplest and nearest to a straight-line organization with simple and direct incentives; for intricate work much emphasis must be laid upon an advisory staff and upon continuous educational direction.

Where originality is essential, as in the typical jobbing machine shop, or in specialty selling, a considerable decentralization of authority is desirable. For rapid or irregular growth only a skeleton of the final structure is likely to be practicable, and considerable changes and many additions of outside men are to be expected; whereas with slow and steadier growth more dependence can be placed upon promotions from within the ranks. And for members in close contact simple measures of coordination like committees or conferences may be sufficient; where in a wide-spread organization even very elaborate and expensive measures may prove inadequate.

Very often the problem of relating structure “to task” offers itself in the converse form: can a given organization successfully undertake this or that new task? How far into small specialties can a company established in the mass production of staples go? How effectively can a retailing chain manufacture its own merchandise? A similar problem is involved in the common discussion of the extent to which government can undertake any of the tasks usually carried on by private business. To insist that a government should not go into business is to say nothing; all governments must be in many sorts of business. The question is what are the essential factors of the particular business under discussion and the real nature of the unit of government suggested to run it?

One of the factors, for example, which affect a judgment as to what specific business a government might run, is the degree of choice which enters into the purchase of the product of that business. Water has no styles. It is furnished by a considerable number of governmental organizations with success. Transportation offers a wider, though not extremely wide, field of choice; while clothing’s field is almost without limit. It is upon precise details like these rather than general theories that the question hinges.

On task distribution

When any task gets beyond the capacity of one man so that another man has to be called in, there must be in some form a distribution of the work; and for each additional man thereafter a new line of distribution must be drawn. Someone must be put in charge to correlate and guide their separate efforts and when in its turn this task of guidance grows beyond one man’s abilities some line or lines of redistribution have to be drawn through it.

The general considerations which govern these distributions of tasks among men constitute the underlying principles of departmentalizing. These principles pertain even to those first distributions of task where only one man at a time is involved, that is, where there are being formed “departments of one man each.” Even in the largest organizations, the smallest sub-departments must in the last analysis finally distribute the work they have to do among single individuals— must divide their work into departments of one man each. To make any one of the assignments carelessly or stupidly may not seem important; but upon the aggregate of them rests the whole structure of the organization.

The individual duties of the members of an organization must be so assigned that most of them are within the powers of most people, a very few jobs calling for the full powers of men of high ability, and other jobs ranging between in appropriate numbers. Where the character of the personnel is known, the distribution obviously should be made with as much regard for the particular capacities of the separate individuals as knowledge will permit; jobs must so far as possible be fitted to the capacities of the men available.

Where the personnel is not known, or is known to be typical, or is likely to change frequently, these capacities must be assumed as normal to the classes of people to be drawn from. The analogy between organization structure and the structure of a cellular organism is suggestive in many ways. Each has its organs or departments interdependent in varying degrees of intimacy, but none completely independent. In so far as an organization is to be regarded as a unit, the lines between its constituent parts must not be or be thought of as lines of division. In reality there are no actual lines of division through an organization; all the forces within it blend into, affect, and are affected by each other; we draw lines merely to help ourselves understand and handle the organization, because we cannot grasp or handle it as a whole.

When an organization is thought of as an organism, the words “superior,” “higher,” “top to bottom” are seen to be thoroughly misleading. There are men whose responsibilities include within themselves the responsibilities of other men; such men have the duty of adding to or subtracting from the separate responsibilities of the men in their charge, and so may properly be called men of larger responsibility. But on account of the implications of moral worthiness which are inextricably tied up in them, the words “higher” or “superior” are especially to be avoided. “Subordinates” as a matter of fact, are not there to serve “superior officers.”

Each man in each place has a function to fulfill, normal to the particular organization; he must perform that function in such a manner as best to help the organization attain its objectives; in the words of Miss Follett he must obey the “law of the situation.” There will be other men who have the responsibility for examining the degree to which he obeys this law; but it is this law, not these men, which really measures his fulfillment.

The habits of many generations and the extent to which all organizations have borrowed from military forms have, of course, strongly established the usage of such words as “superior” and “subordinate.” But the evolution of the modern industrial company from the one-man concern into the widely owned corporation, in which no single man’s will or caprice can be absolute, has brought about changes which lead towards their gradual disuse. The three principal limiting factors of departmentalizing are size, range of required abilities, and possibilities of intercommunication.

Even in the simplest standardized tasks each man has his limit, imposed sometimes by muscular, sometimes by psychological factors, and more often by both. If a man is really to lead men—to influence those immediately under his direction—there will be some maximum number of them to whom he can give his fullest service. To spread himself out too thin over a large number is notoriously poor management practice; and to have too small a number unnecessarily restricts his field of influence.

The maximum varies slightly with the nature of the man and of his associates and of his job, but not so widely as is often supposed; for anything more exacting than the direction of simple or uniform mechanical work it seldom runs beyond six to twelve people.

The second factor in deciding what the work of a department, a worker, or an official is to be, is that the abilities required should be kept as nearly of a kind as possible, so that no unnecessarily wide range of knowledge, or variety of special adaptabilities will be demanded. Jobs calling for a combination of abilities, rarely met, must be rarely set either for managers or men. Great strength and nimbleness will not often be found together; nor will the faculties of painstaking analysis and persuasive salesmanship.

The ability to study, plan, and make decisions is not often to be found in conjunction with the ability to influence men, and yet it is this combination which is most often wanted in a manager. It is also extremely rare to find men who can carry on research, and routine work as well; one or the other will be allowed to lapse, and since routine is the more insistent it will usually be research which is neglected. Research departments, therefore, are commonly separated carefully from operating departments; and sometimes pure research has to be separated from the more nearly routine work of applied research.

The third limiting factor in determining the constitution of departments lies in the possibilities of intercommunication among its members. This factor is obviously completely satisfied in “departments of one,” but contact problems afford difficulties which grow rapidly when a department gets beyond the possibility of full and continual audible and visual inter-contact. Since a department head, foreman, or manager is the clearing house of his department, contact problems within a department commonly present themselves as problems of contact between manager and members.

Adequate contacts are always easier to provide for tasks which are simple and which vary little from one another. A very superficial contact may suffice for a crew of casual laborers; but with a permanent crew something more than a knowledge of the members’ names and what they are doing is desirable. With the widely scattered members of a field force of salesmen or service men very elaborate measures may be needed to afford satisfactory contacts.

The following quotation summarizes Army experience in departmentalizing: In larger organizations, the number of units that can be effectively commanded, or directed by one commander, depends on the means of communication and on the size and functions of the subordinate units. The number of these subordinates rarely exceeds six. The maximum size of a unit is limited by the ability to exercise command and the mobility to perform its intended task in combat. The minimum size depends on the necessity for economy of men and material, but is limited by the requirement, that the unit be able to accomplish its intended combat task through the development of its maximum fire power and through its ability to sustain this fire power until the completion of the task. Mobility decreases as size increases.

In armies as in industrial organizations the distribution of the whole task into departments is determined by a consideration of all the limiting factors together, seldom by any one alone. Simplicity and similarity of task allow of larger units; difficulties of intercommunication and contact compel the formation of smaller units. In the sense of the word as here used, a department may also be a grouping of departments each of which is itself a grouping of departments, and so on. Since the same principles apply right through, it is natural that the structure forms of each of the parts of an organization should be consistent with each other and with the whole. In any organization the parts partake of the nature of the whole; what is true of a large segment is likely to be true of the whole and of a smaller one as well. It will often be worthwhile even to examine the similarities and the differences between the real tasks of the man at the bench and the general manager.

The work of the chief executive is not unique; it has many of the characteristics of the work of a department head, but the substance it deals with may be vastly different. It is too seldom realized that the foreman’s job relative to the matters and men with whom he has to deal is very closely like the general manager’s job relative to the matters and men with whom he has to deal. Each could better understand the other if the objects of their activities commanded less of the center of attention and left the field more to the essential nature of their activities.

If an advisory management council or executive board is good for the organization, it is always worth asking how far a smaller council or board would be good for any department or division; if it is wise to functionalize off a general purchasing agent, should there be a partial functionalization within each department for attention to purchase requisitions and what they involve? Recent experience of large corporations and mergers has led towards making each departmental unit as nearly a complete and self-contained organization as practical considerations of cost allow. The lines of authority run to and through the head of each unit and are supplemented by advisory lines which tie together and to the central office all those men performing similar functions in each of the units.

During the last twenty years there has grown into use, especially among business organizations, the term “functionalizing,” to distinguish, though not always very clearly, the establishment of departments to give special types of service, usually advisory, to the more strictly operating departments. They correspond to what in the older Army parlance are called “staff” departments or “staff” officers in distinction from the’ ‘line.”

It has been said above that, in order to avoid unnecessary complexity, department lines have to be drawn so as to include within them jobs, as far as possible, similar in nature. The similarity may be in equipment used, goods handled, types of people and trades dealt with, territory covered, or in the special mental capacities required. To departmentalize chiefly with respect to similarity of the necessary mental characteristics is what is most commonly meant by functionalizing. The process is by no means new.

The development of an organization to meet the demands of growth always includes, sooner or later, the relief of operating executives from some function of growing complexity by centralizing its study and supervision. Forty years ago it was common practice for each of the heads of producing departments to do his own buying and to control the warehousing of his raw material and finished goods; now these activities are more often considered special functions.

Selling and accounting were earlier functionalizations, and together with purchasing and warehousing have in most cases been now so long established that they have more the character of line departments. It has often been found that if any particular project, such as a wiser handling of personnel or better maintenance of machines, is to be carried out by an organization, it will generally be because some specific, appropriate provision has been made that it should be carried out.

The failure of force and drive

General preachments which leave such a project the by-product of several line officers’ work are likely to accomplish some harm and little good. Most effective when it can be afforded is to make the project the sole occupation of some individual or small group with advisory relations to the line departments. Then, if they fail in it, they fail in all their work. For this reason in more recent years business organizations have formed staff departments for personnel management, rate making, planning and routing of orders, internal trucking, and methods research; and, in the sales field, for working out standard practices of hiring and training salesmen and uniform policies of styling, pricing, and merchandising.

A staff officer’s relation to line officers is that of helper, critic, teacher. The staff should be able to see their special fields of interest more broadly than a line man can and point the practical paths of progress further ahead. A line officer as an executive head of an operating department in any ordinarily complex organization must, therefore, expect to work in close conjunction with a variety of special advisory experts.

“Command, Staff and Tactics,” prepared by the General Service Schools at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., from which the following quotation is taken, contains much of interest to the student of organization engineering. The history of the evolution of Army organization as it has worked itself out by trial and error over many centuries is rich in suggestive material.

Staffs: In this grouping of units under one commander, a point is soon reached in the ascending scale where the multiplicity of details devolving upon the commander is too numerous to be handled in person and leave time for consideration of the broader phases of command. Beginning at this point each unit is provided with an appropriate staff. By the term staff is meant the personnel who help the commander in the exercise of the functions of command by professional aid and assistance.

The introduction of the staff into a unit does not alter the basic principles of command and responsibility. General staff officers assist the commander by performing such duties pertaining to the functions of command as may be delegated to them by regulations or given them by the commander. Technical and administrative staff officers assist the commander and his general staff in an advisory capacity in matters pertaining to their special branches.

The staff does not form a link in the chain of command, or in any other way take from or add to the authority and responsibility of commanders. Divisions and larger units have both a general staff and a technical and administrative staff. In units below a division, the staff consists of officers and enlisted men assigned to duties corresponding to those of the staff of higher units. There is no question here of “divided authority,” though it is in a sense divided just as it always must be as soon as departmentalizing is begun.

Where the evil of divided authority can be complained of, it is usually because of some confusion in the drawing or in the explanation of departmental lines. It may be a little complicated for A’s man to work under the advice of B, but it is not at all uncommon in a large-sized organization. The more complex the problems of an organization, the more essential is provision for the ordering and systematizing of its advisory staff relationship. Sporadic, unsystematic, and irresponsible advice may be worse than none.

There is a responsibility or accountability that goes properly with the advisory functions just as there is with the executive function. The executive is usually said to have “final” responsibility because he must turn the advice into action, but the advisers have no less to be held accountable for giving advice which leads to wise action.

If men’s responses were uniform and perfect, both as to speed and direction, there would be nothing more to the current operating problem of an organization than to provide the original stimuli which should thereafter impel men and groups of men to act steadily along a set of desired lines. But in complicated and changing situations, where work can be only imperfectly laid out and these layouts imperfectly followed, there must be what is practically a daily refinement both of the laying of the lines and of the impulsion. This is primarily a process of coordination and redirection, and to provide for it there must be men with appropriate authorities placed throughout the organization.

Wherever jobs can be specified reasonably well in advance, and men can be incited to perform according to specifications, “bossing” is worse than waste. Hence, the progressive conquest of the impediments which make this advance specification or planning impossible is itself an objective of organization engineering. Control degenerates into mere bossing-about, unless it includes a continuous attempt to make itself unnecessary.

Anticipation and prevention

Each organization executive within the limits of his own position has, therefore, a double task—current direction of such activities as are not yet made subject to advance planning, and constant enlargement of the area of his work which is covered by planning. Planning is the effort so to lay out work in advance that the minimum of current coordination or supervision is necessary. Obviously, almost all work in order to be done at all must be planned, at the very least informally and a few minutes ahead.

Obviously, on the other hand, not many tasks can be planned in full detail for years ahead. One job of organization engineering, therefore, is to determine how far and how precisely it is profitable for each group and each individual to plan and lay out his job. Too much planning and too little planning both result in a lessening of the power to meet emergencies or other changes in conditions—too much planning, through the temptations it offers to be inattentive to such changes, too little by requiring so much attention to repeating detail that not enough can be given to subtler or deeper factors.

Plans with insufficient areas of free action or whose provisions for meeting changes and exceptions are too stiff may give rise to what is known as “red tape.” Plans too loose and free invite internal conflicts, duplications, and loose connections. To steer its efforts steadily on its appropriate course, an organization must look ahead, but must know the limitations which restrict its power to see ahead.

Analysis and planning take time, and quicker results can be gained without them; but in the same sense, a few pairs of shoes can be made by hand more quickly than by waiting to construct a hundred different shoe machines. Where the final quantity of work to be done is sufficient, even the most elaborate analyses and plans may be worth waiting for and worth their cost. It is the custom of general staffs of armies to study in advance with considerable care what it would be necessary and effective to do in case this or that contingency should happen.

There are many occasions upon which this is a wise policy for the general staffs of many other kinds of organizations to follow. For example, at any time during periods of business prosperity it is likely that a period of recession is ahead—at least this has always been true in the past. The exact nature of the period can seldom be foreseen, and specific provisions to meet it cannot be worked out in detail, but general provisions can be; and in any case it can be arranged that such a period will not catch an organization wholly surprised and mentally unprepared.

Because the intricacy and difficulty of planning increases more rapidly than the size of the organization, and because some steps are risky even when taken experimentally, large organizations, in spite of many advantages, find many special handicaps when placed in a rapidly changing environment.

Small and new organizations have no weight of established practices to hamper a radical experiment in styles of goods or in packaging. They have little to lose and much to gain; like young trees growing in the forest, they can take advantage of footholds too precarious for veterans, and they can bend to the winds and turn to patches of sun with more suppleness.

It is partly for this reason that the advantages of size in a competitive regime do not result in one huge organization dominating and finally absorbing all. The specifications of any plan are the “standing orders” of that unit of the organization to which they apply. They must, of course, be specific as to the field they cover and hence either directly, or by implication, define the boundaries of each man’s areas of free action. Such specifications may be general, as when they prescribe the usual opening and closing times of a factory; or detailed, as in the description of the speed, feed, and depth of cut in a lathe operation.

At a minimum they may do no more than designate the man to whom the member of the organization is to look for his daily instructions. They may leave wide areas of free action with no provisions even for reports; they may prescribe a standard procedure but allow of exceptions which must be followed by special reports; they may describe the usual course of behavior and designate men who may alter the course; or they may prescribe an invariable routine. One set of circumstances or another may justify every degree of generality, looseness or even vagueness in standing orders, but, whatever their nature is, it is essential that to the greatest extent possible they may be and are so understood by all concerned in them that every man will translate them into action in practically the same way.

Flexibility for disturbances

It is partly on account of the great difficulty of finding a set of words which will make uniformity of interpretation possible that it is wise to provide for fairly wide and free discussions while plans are being developed and put into specification form. It is quite evident that a prime requirement of ideal planning is that it shall cover all possible action of the unit of organization to which it applies, either by prescription, by exception, or by the specification of areas of free action; it should have no gaps and no overlaps. The questions involved in deciding who shall work out the various plans and specifications, and who shall make exceptions or control the areas of free action, determine the assignment of executive authority.

The limits of such authority are dependent upon the specific knowledge and abilities of the men who hold it. For a man’s power to fill a position requiring the determination of plans and the control of exceptions lies in his knowledge of objectives, conditions, and men, on the one hand; and his judgment and forcefulness, on the other. If each member of an organization is in any realistic sense to be held responsible for the right exercise of his authority, there must be definiteness and accuracy in the record of what he has done, which must be periodically compared with the specifications of his job. To “give a man responsibility” may be mere words, an act of faith, or an actual, if unacknowledged, abdication.

In good organization practice the essential factor of responsibility is accountability, which is on the whole a safer word to use. It must be held to mean the comparison of a record of performance with some standard of what ought to have been done. To say that responsibility must go with authority is merely to state the general rule that the performance of every organization member must be recorded and judged against an attainable standard if the organization is to be of maximum effectiveness. That authority must accompany responsibility is a bare truism, since no man can be held accountable for results he has no power to attain.

Good records, well used, are instruments of impulsion as well as of direction; they are incentives as well as guides to future accomplishment. The accuracy and cogency of recording and reporting have to be developed as the organization develops, and elaborated as its problems elaborate. Records easily go dead because they are only partial pictures, or too long delayed, or full of useless figures, or unimpressively presented; or because they are superficial, verbose, or otherwise lacking in power to get across.

Poor or unnecessary recording, moreover, tempts men to characterize all records as bad, and so to neglect proper and essential records. Record making is a skilled trade and requires skilled people. A record ought always to state its limitations so that it won’t seem to mean more than it does. To-day we no longer hear criticism of our cost records; because they are accurately made out by well-trained men and because they are correctly labeled as to what they mean and do not mean. Fully as important as this is what we have learned about how to use records.

When we first used many records, we tended to think that records were the “whole thing.” We felt that they were “facts” and no one had any right to differ with facts. Now we have learned that a record is only part of the facts and cannot stand alone. It always needs someone who knows the whole situation to explain it—to say just how the record was made and just what the conditions are that affect the record.

The most important thing that records do is to help our judgment to be impersonal. People need something to help them remember correctly and to prevent their personal feelings from influencing them too much. Many things that have happened during the past two or three years have taught us how dangerous judgment is without records. I think that by and large the management it just about as afraid of judgment without records as of records without judgment.

The almighty organization chart

The degree to which executive authority is to be centralized or decentralized is determined chiefly by the extent to which the necessary knowledge is in the home office or in the field—in the factory manager’s office or in departments or sub-departments. There is no magic in the mere terms centralization and decentralization. Action must take place in the field; and it must be made consistent, and coordinated with other action through some center or centers. To just the extent that those at the center know more than those in the field, to that extent they can give rules which will coordinate, guide, and help action. This extent will change with experience and vary with the relative qualities of the men concerned. The proper area of free action in the field includes all matters upon which knowledge cannot be gained in the central office in enough detail or with sufficient promptness.

In the many lively business controversies staged over the relative merits of centralization versus decentralization in management, the truth, on close examination, appears to be that neither of these courses would ever be exclusively adopted by a manager in his full senses. For anything like effective work there must always be a degree of each, dependent upon a considerable number of circumstances.

As a general thing, procedure pretty well known and whipped into accustomed methods can be centrally controlled in some detail, new and unknown factors being left to the judgment of local heads, that is, decentralized. Then, as these unknown factors reoccur sufficiently often to become familiar, the central office may work out best methods of meeting them, and so exert centralized authority. The locus of current control will shift from time to time between the center and the field in accord with the shifts in focus of the more pressing problems of the times.

Wherever that focus is, there good management will concentrate its forces. For a sales force, this would mean more decentralization in a buyers’ market and more centralization in a sellers’; for a factory more centralization when production is regular and uniform, and more decentralization when irregular or highly specialized. Even in the handling of those areas of activity left free by central rules and in the meeting of exceptions and changes of conditions, authority is in essence the working out of plans which meet conditions and are understandable by those they affect. Hence, as much in the field as at the center the planner must have a knowledge of objectives, conditions, and personnel. Authority in both cases goes with knowledge and ability.

A chief difference lies in the span of time and the variety of conditions and personnel to be covered by the planning. The time span to be covered by central management may run into years, while at the edges of the field, planning may have to run merely from day to day. In cases of emergency, planning and execution are virtually simultaneous, so that there is no practical distinction to be drawn between them.

Wherever the decentralized authorities are numerous and large, the task of continuous coordination of their actions is of pressing importance. To depend for coordination wholly upon up-the-line-and-down again contacts, discussions, and reports is practicable only in the simpler and smaller organizations. In unmodified line organization, when a need arises to alter the behavior of F and G in order to avoid conflict between them, communications must pass from F to D to B to A, to C to E to G, and hence a degree of understanding of the situation is required of each.

In large organizations this journey is too long for very many cases to travel it successfully— or for any which demand quick coordination; and the range of understanding demanded of the line officials is too wide to be humanly possible in matters at all technical. But in organizations with very simple tasks the system is practicable, for there are neither many cases where F and G affect each other, nor are there many of a very technical nature.

Where there is need of much close coordination between separate line departments and where staff begins to develop, intimate and immediate lines of cross-contact must be established so that plans and orders may be based upon the broadest knowledge possible and uniformly understood. The methods by which these cross-contacts can be effected and controlled must be various to meet the multiple variety of situations to which they are to be fitted. The whole problem of current contact among the units of an organization is a principal preoccupation of organization engineering. Reports, letters, visits, special conferences, periodic publications, committees, councils, telephones, moving into neighboring offices, are some of the means it can use.

It would be ideal if all contacts could be close and perfect, but economies of time and money prevent. Hence, means of contact must be calculated to fit the physical and psychological difficulties of each set of cases and the net value of a given degree of mutual understanding in any case. One great obstacle to the harmonious working together of the heads of divisions is physical distance.

Letter writing is a very imperfect substitute for contact. In one very large corporation where the half-dozen operating vice-presidents were separated, the lack of coordination among even the three who had their offices in different parts of the same city was so complete that in the words of one of them, “We competed with each other much more vigorously, ingeniously, and destructively than we ever dreamed of competing with competitors.”

When they were brought together it was carefully provided that they should be actually on the same floor of the same building. After two or three years of strenuous readjustment their conflicts began to be joined at such early stages that they could acquire no serious conflict tone and were readily adjusted. The need for coordinating the activities within an organization, and the difficulties of doing so, increase much more rapidly than merely in proportion to the number of its departments, line or staff.

The large organization can no more be made successful if it is nothing but an enlarged or multiplied small one than the great ship can be made by enlarging all the dimensions of a small boat. Of first importance as an organization grows large are the ties which bind its parts together; and the larger the organization, the stronger, more elaborate, and more perfect must these ties be. The authoritarian lines of communication—running from the head down—may be enough in a small group, but become rapidly, if not always obviously, insufficient as the group develops in size. The science and art of providing cross-ties, cross-channels of communication, contact among correlatives, are at the core of successful organization engineering. In conclusions from significant experiences during the World War, he leads up to his discussion of the principles of coordination with the following historical summary of the successive steps toward better coordination as they actually occurred.

This was the climax of the development by which cooperation between the Allies shifted gradually from a diplomatic to an administrative basis. We have seen how, before the war, negotiations between the British Board of Trade and the French Ministry of Commerce would pass through two Embassies or Foreign Offices en route in both directions; how the question asked of a specialist in London and the answer of the corresponding specialist in Paris would be transmitted, and perhaps transmuted, by two sets of necessarily non-specialized brains and pens.

We have seen the slow tentative process by which these methods were gradually transformed under the increasing need of Allied cooperation. Departmental Ministers met in occasional conference and dealt direct with each other and not through their Foreign Offices. The whole system was made more workable in practice, although not transformed in principle, by the establishment of the Commission Internationale de Ravitaillement which relieved Allied representatives of the formalities of diplomatic negotiations, but left them still cut off from direct contact with British departmental officials. Then the paramount exigencies of the wheat and shipping problems forced the development further.

Members of the Allied food departments met in direct association to allot the available wheat among themselves and to put it in common. The British shipping authorities negotiated shipping arrangements direct with the corresponding authorities in France. But by this time shipping had become the limiting and, therefore, the determining factor in all supplies. The British shipping authorities by allotting so many ships and no more to France and Italy were determining the limits of the French and Italian imports. In doing this, they were scarcely more expert than supply representatives would have been in settling the allocation of ships.

And so at last the final stage was reached. The supply departments of the different countries were themselves linked together from within. The national administrations now touched each other, not at one point (the Foreign Offices) nor at half a dozen (the Ministers of the main departments), but at scores (the officials and experts responsible for the detailed controls). And the contact was no longer occasional and irregular, but continuous. The French representatives no longer met the British and Allied representatives to discuss a wide range of different subjects under negotiation between their countries. The French wool official dealt with the British and Italian wool officials and was not concerned with what his colleagues for cotton or timber or coal were discussing in other committees with the corresponding experts. Thus the international machine was not an external organization based on delegated authority; it was the national organizations linked together for international work and themselves forming the instrument of that work.

Bottom up work coordination

Miss FoIIett has emphasized many times the necessity of adequate cross-contacts. In one lecture she says: “It is not sufficiently recognized that coordination is a process which should have its beginnings very far back in the organization of the plant. You cannot always bring together the results of departmental activities and expect to coordinate them. You have to have an organization which will permit an interweaving all along the line. Strand should weave with strand, and then we shall not have the clumsy task of trying to patch together finished webs. [And in “The New State”:]

“If Parliaments are composed of various groups of interests, the unification of those interests has to take place in Parliament. But then it is too late. The ideas of the different groups must mingle earlier than Parliament . . . We do not want legislatures full of opposing interests. The ideas of the groups become too crystallized by the time their representatives get to the Parliament, in fact they have often hardened into prejudices.”

Interdepartmental sabotage is easy to accomplish and difficult to detect. Mere non-cooperation exacts a ruinous toll. In the frictions between executives entrusted with responsibilities, which are in fact common, but are kept separate except at the top, the good of the company is often overlooked in an effort to escape extraneous domination or interference.