Class Acts

The withdrawal of efficiency

Justification of Ca’canny

Joseph J. Ettore 1913

The struggle of the wage workers for industrial freedom is fast assuming proportions that challenge the attention of all classes in present day society.

The oppressive conditions under which the vast majority of wage workers must live is forcing the members of that class to seek for a means of relief. That search for relief must of necessity be a question for knowledge. It is with the sincere hope of being able to in some measure fill this demand for knowledge on the part of my class that this pamphlet has been written..

With the ending of the revolt of the slaves in the Textile Mills of the New England Textile districts, the struggle breaks out in the Lumber districts of the South. The answer of the masters of the bread in the Southern country is the same as the answer of their kind in the far away New England States. That answer is, the leaden bullet of the hired thug and the soldier; the club of the special policeman; the disease-ridden jail with the shadow of the gallows ever present. Cultured New England is joined by the aristocratic South in a feast of blood.

It is, therefore, fitting that I should dedicate this pamphlet to fellow worker A. L. Emerson and his sixty-four fellow workers who are now awaiting trial in the courts of Louisiana, because they dared to raise the banner of revolt against the reign of the Lumber Kings of the South. Therefore, to them it is dedicated, and I sincerely hope that its sale will help to provide the funds necessary to secure for them their freedom, that they may once more take up the work of the Cause they have served so well in the past.

Rising out of conditions that have long become unsupportable, that were never intended should benefit but the few, conditions that are a living outrage on the lives of the working class of the nation; Industrial Unionism, the One Big Union, of all the workers of all trades and all industries; striving energetically and with devoted enthusiasm for the one burning ideal and hope of the world’s toilers Solidarity to the end of accomplishing final and complete industrial emancipation, is no longer a mere plan or scheme to foist upon the wage workers of the land.

Witness France, very recently and most successfully the efforts and triumph in England. Hear the echo and rumbling. The masters at home will soon have to deal with it much as they may dislike to or pretend and prate that the “American wage workers are too level-headed and steady to run off at a tangent like the hordes of Europe.”

It is now a living force, a movement aiming at certain immediate objects and imbued with definite and lofty principles, applying up-to-date tactics that mean ultimate success. Not seeking to live on the tradition, history and glory of a past, but is a determined and enthusiastic effort on the part of conscious workers to live and struggle for better working conditions now and never lose sight of the main object—Emancipation.

Hitherto the effort has been ignored, laughed at even by men and women that pre-tended very noisily to know the aims and hopes of labor. This element has arrogated to itself the right to program the workers’ activities. But in spite of opposition, open and secret, by self-appointed guardians and enemies, the ideas and the movement is reaching a point that compels attention particularly from the enemy. It has come on the floor for discussion and all amendments offered, side-stepping done, calumny, efforts to postpone and conciliate, will neither adjourn nor abate the discussion.

It is said that our ideas are impractical. That is true. From the standpoint of old institutions, interests and their beneficiaries; the new is always impractical.

We also hear it said that our efforts are dangerous. Yes, gentle reader, our ideas, our principles and object are certainly dangerous and menacing, applied by a united working class would shake society and certainly those who are now on top sumptuously feeding upon the good things they have not produced would feel the shock.

“The working class and the employing have nothing in common.”

That is more and more forcibly and eloquently being brought home to our class. Whatever failure the agitator may make in impressing the toilers of the conflict of interests between employers and employees, is most eloquently and convincingly impressed now as in the past, by the policemen’s clubs, the whip and the mace of State troopers, militiamen’s bayonets, soldiers’ machine guns, jails, bull pens and scaffold, and such other “civilized weapons and methods” that capitalism needs to impress on the slaves the sanctity of property rights and “freedom to labor.”

Certainly there can be no common interests between those who own the tools, the machines, factories, mines, mills and land, with the workers who do all of the producing. One class does all the work, produces all, suffers all the hardships necessary to accomplish the task. The other class owns, but does not know, nor cares to know, how to produce wealth, yet persists by rights that it labels “legal” and otherwise to live upon what it does not produce.

“There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people, and the few who make up the employing class have all the good things of life.”

One class works long hours under conditions generally and necessarily established by and suitable to the masters of industry, receives low wages, so that there may be high dividends and profits for the masters. For it must be borne in mind longer hours mean greater wealth produced, low wages mean greater profits for the capitalists. Shorter hours mean less production by each worker or group of workers, therefore the expense to the masters is greater to produce a certain amount of wealth. High wages, shorter hours, better shop conditions that will protect life and limb are objected to by the capitalist for a thousand and one “reasons,” but really because it all means greater cost—thus less dividends—resulting in less palaces, less automobiles, less silk dresses for their wives and daughters.

To the working class, shorter hours means less exertion of energy, longer lives, more workers employed, less competition for jobs, higher wages, more bread, better houses, happier lives.

Members of the upper class are known for eating too much. Members of the laboring class die for want of enough to eat.

Who can be so stupid or knavish as to talk of peace between these two classes?

And yet there are some, quite a few, who do so, particularly after a feast at a Civic Federation meeting.

“Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production and abolish the wage system.”

We can just about hear a chorus of well kept and well fed ones, “All this is wrong,” “You will thus overthrow all established usages, laws, customs and institutions.”

But the conscious worker who knows what springs guide the minds and mouths of the maintained ones shout, “Hosanna! That is right! More power to you!”

“These are ideas subversive to our civilization, they strike at the very roots of things, they endanger the rights of private property upon which our Republic is based,” hints the owner of industries, the exploiter and despoiler of labor.

“Against all laws, constitution, precedents and authority, it’s a conspiracy; yes, sedition, treason,” says the man in legal vesture.

“Free lovers and enemies of institutions long established and respected,” thunders the moralist who may be drawing his rents from gay houses.

“They would destroy our union and en-danger the amicable relations now existing between employers and employees,” croaks the “labor leader” of the craft union.

“For the interest of civilization, that society may be saved and in line with our duties, the place for folks holding such dangerous notions is the jail,” cry the police.

“Lynch them,” shouts the whole motley crew who benefit greatly from the present economic arrangement.

“Amen,” sanctimoniously grumbles the black-robed hypocrite who alleges to be the minister of God and a follower of the Lowly Nazarene.

And thus society is defended, saved and blessed.

This motley crew would be indeed ungrateful if they would not offer their defense and hosannas to a society that is so generous to them as to feed and clothe them with the best and yet require no labor from them.

As long as one class performs no function in production only as parasites and social sponges, is too lazy and impotent to work, but lives and riots in plenty—and our class, the wealth producers—produce all, makes all, digs all the coal; in a word, makes life worthwhile and brings into being by its labor and travail all that life necessitates, and yet lives in want, is paid wages which at best and highest only represents a part of the entire product; a struggle is inevitable.

Those who are serious and who respect themselves and their education will not dispute that labor with its hands and brains produces all wealth. We industrial unionists hold, and every day experiences tend eloquently to prove and convince all that our contention is correct.

In the ratio as capitalists grow stronger and more secure in their ownership of industry, more and more parasitical in production; they also grow arrogant with the feeling and satiety of power; they become tyrannical in their conduct towards the workers; just in that ratio the laboring class develops, in power by virtue of the great numbers assembled together in various industries, in consciousness by the experiences and lessons it receives in its daily struggle for more bread and greater economic rights. Its vision extends further than mere shorter hours, higher wages and matters of that nature.

It acquires class feelings, class knowledge and conceptions with a realization that, struggle as it may, gain as many victories as possible; the age-long class conflict can only come to an end when “the workers of the world organize as a class,” change society from the very basis through the medium and power of their industrial organization and keep on producing wealth, not as hitherto, only for the partial benefit of the producers, but on the principle that “Labor is the producer of all social wealth, therefore, to the producers belongs the full product of their efforts.”

Unquestionably from the standpoint of the coupon clippers and their retainers, anything the workers do that either tends to merely obtain more bread or any efforts that tend to unsaddle the masters altogether is considered wrong, ethically, legally, religiously and by every other measurement.

From the standpoint of the masters those who aid, abet and sanctify their right to plunder the workers are considered paragons of virtue and good citizenship.

A scab who works while men and women are struggling for humane conditions is hailed as a true type of “an American hero.” Those who willingly work for low wages, satisfied to work long hours under miserable conditions, never even whimper, refuse to band with their fellows in a common effort to better things, are styled “The independent American citizen who refuses to allow the pernicious doctrines of labor agitators to sway them from their patriotic duties,” etc. The judges, the procurators of the State, the police and soldiers, who shoot, club and imprison in the interest of capitalist property and social interests are hailed as the “Saviors of Society.” Those who, under the cloak of religion and alleged loyalty of the Nazarene, offer prayers to the rich and command the poor to be satisfied with their lot on earth, who apologize and offer extenuations for child labor in the mines and factories—are set up as the very pillars and columns of Order, Law and Religion.

But if history teaches right, we know this much—right and wrong are relative terms —and it all resolves into a question of Power. Cold, unsentimental Power. From the standpoint of accepted law, morals, religion, etc., the capitalists are considered right and justified in their control and ownership of industries and exploitation of labor because they have the means to hire, and have organized a gang that skulks under the name of “Law, Order and Authority,” that is well paid and well kept to interpret and execute laws in favor of the paymasters of course.

Our country has been ravaged and stolen by industrial pirates and yet, learned judges have decreed that it was “legal.” Attorneys and politicians have written lengthy briefs and argued long and eloquently, preachers have spoken wise sermons; in short, whatever the king has done, the courtiers have most humbly considered right and the guards and men-at-arms been ready to see that the slaves did not rebel against it all.

Prepared to carry out the capitalists’ every will, this kept-crew is well paid, entrenched and armed, and while it hides under the silk skirts of Mesdames “Law and Order,” is as desperate and brutal a crew as ever scuttled a ship or quartered a man.

Yet with this alone Capitalism could not live.

It is the false conception and consciousness of the vast majority of the workers who hold up the hands of the master class, and in their ignorance look upon the rich as the symbols of all that is virtuous, noble and wise, while if they were conscious of the facts they would look upon private property of socially necessary things as the great social crime and the owners and upholders as so many social criminals, that makes it possible for it to live.

New conceptions of Right and Wrong must generate and permeate the workers. We must look on conduct and actions that advance the social and economic position of the working class as Right, ethically, legally, religiously, socially and by every other measurement. That conduct and those actions which aid, helps to maintain and gives comfort to the capitalist class, we must consider as Wrong by every standard.

The wage system implies the existence of two economic classes. Under it the workers suffer, it means no end of strife, therefore from the standpoint of the workers it is Wrong and it is Right to get together as a class and abolish the wage system, and in its place erect the Co-operative Common-wealth, the Rule of the Proletariat.

“We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever-growing power of the employing class.”

Because they may have some skill and look upon it as so much property, some workers in the past have organized into trade unions; that is, a union for each separate trade. This system of unionism is typified by the American Federation of Labor. It is an organization of one separate union for each trade, although trades may be employed in the same factory or industry.

It is a “unionism” that may have been good enough in its day, when learning a trade was necessary and the vast majority of the workers were required to be crafts-men. The trade unions were useful in their day, same as the ox cart was useful and most essential; yes, of utmost utility in transportation, but it had to make way for something more efficient.

With the ever greater development of machinery and concentration of industries, trade lines are erased, the workers more and more are reduced to one common level of labor and servitude.

The capitalists—not because of any spirit or feeling of Solidarity, but in the struggle among themselves for the products they steal from labor have been driven to concentrate their economic power into huge industries, and in turn the small citizen alliance has made way for the One Manufacturers’ Association or Employers’ Association. They have done away with the trade lines. Their associations are not composed of employers exploiting the workers of one trade, but covers the exploitation of workers of every trade in the industry. So that the “trade union” has become obsolete and now only manages to live on the recollections and bonds of age and traditions.

“The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars.”

With the pernicious system of each trade organizing and looking out for itself, signing contracts and agreements with the employers that bind the workers of a certain craft for a definite and long term of years to work certain hours under certain conditions for certain wages without taking into account and consideration the rest of the workers in the same establishment or industry, workers are divided and defeated.

Experience and history for the past few years abound with instances where workers organized into trade unions in spite of themselves, helped the employers defeat other workers, organized as well as unorganized, skilled as well as unskilled. Cases are too numerous to mention where we have witnessed one set of “union men” scab on another set of workers, also unionists, who were struggling for better conditions. Yes, we call it scabbing, union workers remained at work alongside of strikebreakers, aided, abetted and gave comfort, even to the hauling and furnishing food to scabs in strike-bound places.

We call such conduct by its proper name, hideous as it may sound, the “pure and simple” trade union “leaders” call it “non-interference” or “trade autonomy.”

“Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the workers have interests in common with their employers.”

Trade unions invariably are pledged to the program of the “co-operation of the classes” and prate of the community and identity of interests between laborers and capitalists. The leaders are always talking of the “brotherhood of capital and labor.”

Out of such dangerous teachings comes the justification and the annual feasts, the Civic Federation dinners at the Waldorf Astoria (New York City), where captains of industry, men like Andrew Carnegie, August Belmont and a host of other labor exploiters, whose opposition to the efforts and hopes of labor is well known and has been marked in historical instances, meet in jolly and sumptuous feast with Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor, John Tobin of the Boot and Shoe Workers, John Golden of the United Textile Workers, and so on ad infinitum et nauseam.

They gather presumably to “discuss and help to solve the labor problems” but in fact to partake of the flesh pots they have stripped from labor, to pull the wool over the eyes of the wage workers so that the chains of wage labor may be linked ever more secure on the limbs of our class, that our hopes and ideals may be dragged in the mire and capitalists given assurance of a long day more of safe and contented slavery on the part of the wealth producers.

And now when the history and objects of the Civic Federation have become notorious and its evil practices and outrages are evoking from the many times defeated and betrayed workers curses and protests that reach to the heavens, a second edition of the Civic Federation has been organized under the name of the “Militia of Christ.” Conceived in the sacristy, born on the floor of the St. Louis, Mo. (1910) convention of the American Federation of Labor, held at baptism by preachers and labor leaders, it is a new conjure to keep the workers in a mental stupor and economic slavery.

“These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any industry or in all industries, if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an in-jury to one an injury to all.”

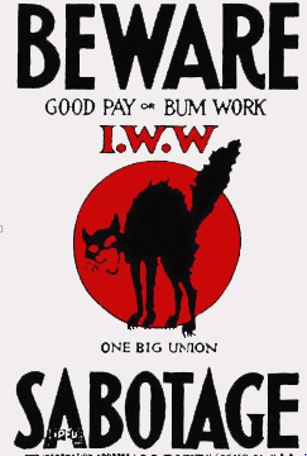

The Industrial Workers of the World is the “organization formed in such a way.” The I. W. W. does not organize by trades, but by industries. All the workers in any plant, factory, mine, mill or any given industry in a given locality organize in one Local Industrial Union. All the local industrial unions of a given general industry are banded together in the National Industrial Union. The National Industrial Unions are banded again stronger in the Industrial Department and then all Departments, six in all, are brought under one head, the General Administration of the I. W. W. One Big Union of all workers, welded together in such a manner that, imbued with the war cry “an injury to one is an injury to all,” all its members can act together in fighting the common enemy.

Industrial Unionists disdain to lower the history and ideals of the working class by entering into contracts or agreements with employers whereby the conditions that are generally forced by the stronger economic power are made a basis for any stated period.

The workers in order to uphold what they are able to wrest from employers must be ever alert and ready with weapons that spell Solidarity and if they wish to advance further, their union must be an army ready to move on short notice and take quick decisions, otherwise it is lost. To be able to do these things it must be free not only in limbs but mentally. Contracts and agreements tend to foist a false feeling of security on the worker and on the day of need—defeat looms up because of the false security—lack of preparations.

“Instead of the conservative motto, ‘A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work’ we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘Abolition of the wage system.'”

As we have stated before there is no gain-saying that Labor produces all wealth. Capitalism is based on the robbery of the workers. Those who own industries but do not work in them, pay wages to the workers and keep profits to themselves. But both, profit and wages, are only the product of Labor. Wages are part of the total product paid to labor. Profit, generally the biggest part, capitalists appropriate to themselves and call it their “legal share.”

Industrial Unionists know nothing of “legal share” nor of “reasonable profits,” as all wealth, however little, acquired with-out labor is robbery. Industrial Unionists know no bargain to life. To talk of a “fair day’s work” is to talk of the pack horse with a fair load on his back; to talk of a “fair day’s wage” is to talk of a reasonably filled nose bag for the horse that has done the packing.

“Fair day’s work and fair day’s wages” imply a question of right and wrong. How-ever, this is a class society composed and divided in robbers and robbed and each class has its own notion of right and wrong, fair and unfair. At any rate, if labor produces all wealth—what else is a fair day’s work except the one the workers will legislate in their union hall stating how many hours to work and that fair payment will be the en-tire products to the producers?

Let a sordid and conservative world talk itself out of its senses and be exploited to the marrow by capitalists. Let the paraders keep on their banner the motto of the middle-age guilds “a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work.”

We workers of the twentieth century will march steady with heads erect, our hearts beating in unison and resolved with our aim fixed on the new society and on our standard unfurled to the free breeze, we have in-scribed the rallying cry and glowing hope of the world’s workers, “LABOR IS ENTITLED TO ALL IT PRODUCES.”

“It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for the every day struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been over-thrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

Such are “dangerous” notions to capitalism. The Industrial Workers of the World propagates these very ideas, it has and will continue—of this we feel sure and satisfied—to meet with the opposition of the employing class. It is to be expected. Such a course on their part but proves the correctness of our principles.

The employers well realize that once the workers begin to seriously organize as a class, with class hopes and ideals, and look out for themselves as a class, with interests distinct and opposed to all other classes, that once the spirit of solidarity takes firm hold in the hearts and minds of the workers, their (capitalists) occupation as parasites will be gone. The danger and fear of having to go to work to live is an ever recurring night-mare that occurs to them ever in their hours of great revelry and riot. They would if reduced to extremes, be willing to make any concession always with the feeling that they can successfully juggle matters so as to keep in the saddle. Therefore is accounted their readiness to look with favor to movements that do not aim at changing the economic relations between wage workers and capitalists.

Compromise for pelf and power has been the one great weapon of the capitalists even in their own day of struggle against the then economic and ruling class. It is a weapon and a means whereby they seduce the rebellious spirit of the workers. A time serving policy. They have cause to fear and dread at the rule of labor.

But you, fellow workers in labor, comrades in suffering, what have you to fear from such program?

You, the hundreds of thousands, aye the millions, who have no shops, no mines, no mills, no land, no home!

You, whose constant companion is want and poverty, whose lot is long hours of hard work for meagre pay, who have only your labor power — yourselves — to sell to a master — in the labor market that is ever crowded — as the only means of making a living.

You, a member of the working class that produces annually an average of $2,400.00 worth of wealth and receives less than $450.00 in wages.

You workers, whose sisters, wives and mothers have been driven out of the homes into mills and factories to compete with you and bring your wages down.

You, whose children have been driven out of the playground and kidnapped from the schoolhouse and strapped to the machine in the mills and shops, that their young lives, their very laughter and joy denied, may be rolled and coined into so many dollars for the pleasure and satisfaction of a few Industrial Herods.

You, of the wage working class, of whom it was required that in one year over forty thousand workers — men, women and children — should be killed in the industries of this nation, burned to death as in the Triangle fire of New York City, their lives snuffed out in coal mine explosions and in a thousand various ways.

The blood of these workers, it seems, was needed to grease and spur the machines in the mills of our masters. Their lives sacrificed all because human beings are cheaper than the application of safety appliances which cost money and would reduce profits; and, since the great God to whom capitalists offer their prayers is PROFIT, human life is destroyed and workshops are turned into so many charnel houses.

So we ask you who, when you are no longer able to live, you ask for more pay and are forced to strike and in reply to your petitions and pleading for more bread receive bayonet thrusts, rifle shots, etc., “What have you, any of you, to lose by opposing the present economic system, banding yourselves with us in one common bond of Solidarity and devotion as industrial unionists to the end of bettering our every-day conditions in the factories, mines and mills?”

What have any of us to lose if we band together in ONE BIG UNION to the end and by it as a medium transform the present system of industrial despotism and economic inequality into one of Industrial Freedom and Equality?

We would lose our chains, our miseries, but gain the world for all the workers, a world fit for men and women to live their lives in freedom of love and labor.

Our opponents may say that this would be “expropriation,” but we will let the poet reply for us :

The Cry of ToilWe have fed you all for a thousand years, There’s never a mine blown skyward now We have fed you all for a thousand years, |

Ca’canny delivers 25% productivity reduction

Elizabeth Gurly Flynn, October 1916

The interest in sabotage in the United States has developed lately on account of the case of Frederick Sumner Boyd in the state of New Jersey as an aftermath of the Paterson strike. Before his arrest and conviction for advocating sabotage, little or nothing was known of this particular form of labor tactic in the United States. Now there has developed a two-fold necessity to advocate it: not only to explain what it means to the worker in his fight for better conditions, but also to justify our fellow-worker Boyd in everything that he said. So I am desirous primarily to explain sabotage, to explain it in this two-fold significance, first as to its utility and second as to its legality.

Sabot is French for wooden shoe.

Its Necessity In The Class War

I am not going to attempt to justify sabotage on any moral ground. If the workers consider that sabotage is necessary, that in itself makes sabotage moral. Its necessity is its excuse for existence. And for us to discuss the morality of sabotage would be as absurd as to discuss the morality of the strike or the morality of the class struggle itself. In order to understand sabotage or to accept it at all it is necessary to accept the concept of class struggle. If you believe that between the workers on the one side and their employers on the other there is peace, there is harmony such as exists between brothers, and that consequently whatever strikes and lockouts occur are simply family squabbles; if you believe that a point can be reached whereby the employer can get enough and the worker can get enough, a point of amicable adjustment of industrial warfare and economic distribution, then there is no justification and no explanation of sabotage intelligible to you.

Sabotage is one weapon in the arsenal of labor to fight its side of the class struggle. Labor realizes, as it becomes more intelligent, that it must have power in order to accomplish anything; that neither appeals for sympathy nor abstract rights will make for better conditions. For instance, take an industrial establishment such as a silk mill, where men and women and little children work ten hours a day for an average wage of between six and seven dollars a week. Could any one of them, or a committee representing the whole, hope to induce the employer to give better conditions by appealing to his sympathy, by telling him of the misery, the hardship and the poverty of their lives; or could they do it by appealing to his sense of justice? Suppose that an individual working man or woman went to an employer and said, “I make, in my capacity as wage worker in this factory, so many dollars’ worth of wealth every day and justice demands that you give me at least half.” The employer would probably have him removed to the nearest lunatic asylum. He would consider him too dangerous a criminal to let loose on the community! It is neither sympathy nor justice that makes an appeal to the employer. But it is power. If a committee can go to the employer with this ultimatum: “We represent all the men and women in this shop. They are organized in a union as you are organized in a manufacturers’ association. They have met and formulated in that union a demand for better hours and wages and they are not going to work one day longer unless they get it. In other words, they have withdrawn their power as wealth producers from your plant and they are going to coerce you by this withdrawal of their power; into granting their demands,” that sort of ultimatum served upon an employer usually meets with an entirely different response; and if the union is strongly enough organized and they are able to make good their threat they usually accomplish what tears and pleadings never could have accomplished.

We believe that the class struggle existing in society is expressed in the economic power of the master on the one side and the growing economic power of the workers on the other side meeting in open battle now and again, but meeting in continual daily conflict over which shall have the larger share of labor’s product and the ultimate ownership of the means of life. The employer wants long hours, the intelligent workingman wants short hours. The employer is not concerned with the sanitary conditions in the mill, he is concerned only with keeping the cost of production at a minimum; the intelligent workingman is concerned, cost or no cost, with having ventilation, sanitation and lighting that will be conducive to his physical welfare. Sabotage is to this class struggle what the guerrilla warfare is to the battle. The strike is the open battle of the class struggle, sabotage is the guerrilla warfare, the day-by-day warfare between two opposing classes.

Sabotage was adopted by the General Federation of Labor of France in 1897 as a recognized weapon in their method of conducting fights on their employers. But sabotage as an instinctive defense existed long before it was ever officially recognized by any labor organization. Sabotage means primarily: the withdrawal of efficiency. Sabotage means either to slacken up and interfere with the quantity, or to botch in your skill and interfere with the quality, of capitalist production or to give poor service. Sabotage is not physical violence, sabotage is an internal, industrial process. It is something that is fought out within the four walls of the shop. And these three forms of sabotage — to affect the quality, the quantity and the service are aimed at affecting the profit of the employer. Sabotage is a means of striking at the employer’s profit for the purpose of forcing him into granting certain conditions, even as workingmen strike for the same purpose of coercing him. It is simply another form of coercion.

There are many forms of interfering with efficiency, interfering with quality and the quantity of production: from varying motives — there is the employer’s sabotage as well as the worker’s sabotage. Employers interfere with the quality of production, they interfere with the quantity of production, they interfere with the supply as well as with the kind of goods for the purpose of increasing their profit. But this form of sabotage, capitalist sabotage, is antisocial, for the reason that it is aimed at the good of the few at the expense of the many, whereas working-class sabotage is distinctly social, it is aimed at the benefit of the many, at the expense of the few.

Working-class sabotage is aimed directly at “the boss” and at his profits, in the belief that that is the solar plexus of the employer. That is his heart, his religion, his sentiment, his patriotism. Everything is centered in his pocket book, and if you strike that you are striking at the most vulnerable point in his entire moral and economic system.

Sabotage, as it aims at the quantity, is a very old thing, called by the Scotch “ca canny”. All intelligent workers have tried it at some time or other when they have been compelled to work too hard and too long. The Scotch dockers had a strike in 1889 and their strike was lost, but when they went back to work they sent a circular to every docker in Scotland and in this circular they embodied their conclusions, their experience from the bitter defeat. It was to this effect, “The employers like the scabs, they have always praised their work, they have said how much superior they were to us, they have paid them twice as much as they have ever paid us; now let us go back to the docks determined that since those are the kind of workers they like and that is the kind of work they endorse we will do the same thing. We will let the kegs of wine go over the docks as the scabs did. We will have great boxes of fragile articles drop in the midst of the pier as the scabs did. We will do the work just as clumsily, as, slowly, as destructively, as the scabs did. And we will see how long our employers can stand that kind of work.” It was very few months until through this system of sabotage they had won everything they had fought for and not been able to win through the strike. This was the first open announcement of sabotage in an English-speaking country.

I have heard of my grandfather telling how an old fellow came to work on the railroad and the boss said, “Well, what can you do?”

“I can do ‘most anything,” said he — a big husky fellow.

“Well,” said the boss, “can you handle a pick and a shovel?”

“Oh, sure. How much do you pay on this job?”

“A dollar a day.”

“Is that all? Well, — all right. I need the job pretty bad. I guess I will take it.” So he took his pick and went leisurely to work. Soon the boss came along and said:

“Say, can’t you work any faster than that?”

“Sure I can.”

“Well, why don’t you?”

“This is my dollar-a-day clip.”

“Well,” said the boss, “let’s see what the $1.25-a-day clip looks like.”

That went a little better. Then the boss said, “Let’s see what the $1.50-a-day clip looks like.” The man showed him. “That was fine,” said the boss, “well, maybe we will call it $1.50 a day.” The man volunteered the information that his $2-a-day clip was “a hummer”. So, through this instinctive sort of sabotage this poor obscure workingman on a railroad in Maine was able to gain for himself an advance from $1 to $2 a day. We read of the gangs of Italian workingmen, when the boss cuts their pay — you know, usually they have an Irish or American boss and he likes to make a couple of dollars a day on the side for himself, so he cuts the pay of the men once in a while without consulting the contractor and pockets the difference. One boss cut them 25 cents a day. The next day he came on the work, to find that the amount of dirt that was being removed had lessened considerably. He asked a few questions: “What’s the matter?”

“Me no understan’ English” — none of them wished to talk.

Well, he exhausted the day going around trying to find one person who could speak and tell him what was wrong. Finally he found one man, who said, “Well, you see, boss, you cutta da pay, we cutta da shob.”

That was the same form of sabotage — to lessen the quantity of production in proportion to the amount of pay received. There was an Indian preacher who went to college and eked out an existence on the side by preaching. Somebody said to him, “John, how much do you get paid?”

“Oh, only get paid $200 a year.”

“Well, that’s damn poor pay, John.”

“Well,” he said, “Damn poor preach!”

That, too, is an illustration of the form of sabotage that I am now describing to you, the “ca canny” form of sabotage, the “go easy” slogan, the “slacken up, don’t work so hard” species, and it is a reversal of the motto of the American Federation of Labor, that most “safe, sane and conservative” organization of labor in America. They believe in “a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work.” Sabotage is an unfair day’s work for an unfair day’s wage. It is an attempt on the part of the worker to limit his production in proportion to his remuneration. That is one form of sabotage.

The second form of sabotage is to deliberately interfere with the quality of the goods. And in this we learn many lessons from our employers, even as we learn how to limit the quantity. You know that every year in the western part of this United States there are fruits and grains produced that never find a market; bananas and oranges rot on the ground, whole skiffs of fruits are dumped into the ocean. Not because people do not need these foods and couldn’t make good use of them in the big cities of the east, but because the employing class prefer to destroy a large percentage of the production in order to keep the price up in cities like New York, Chicago, Baltimore and Boston. If they sent all the bananas that they produce into the eastern part of the United States we would be buying bananas at probably three for a cent. But by destroying a large quantity, they are able to keep the price up to two for 5c. And this applies to potatoes, apples, and very many other staple articles required by the majority of people. Yet if the worker attempts to apply the same principle, the same theory, the same tactic as his employer we are confronted with all sorts of finespun moral objections.

Following The “Book of Rules”

Interfering with service may be done in another way. It may be done, strange to say, sometimes by abiding by the rules, living up to the law absolutely. Sometimes the law is almost as inconvenient a thing for the capitalist as for a labor agitator. For instance, on every railroad they have a book of rules, a nice little book that they give to every employee, and in that book of rules it tells how the engineer and the fireman must examine every part of the engine before they take it out of the round house. It tells how the brakeman should go the length and the width of the train and examine every bit of machinery to be sure it’s in good shape. It tells how the stationmaster should do this and the telegraph operator that, and so forth, and it all sounds very nice in the little book. But now take the book of rules and compare it with the timetable and you will realize how absolutely impossible the whole thing is. What is it written for? An accident happens. An engineer who has been working 36 hours does not see a signal on the track, and many people are killed. The coroner’s jury meets to fix the responsibility. And upon whom is it fixed? This poor engineer who didn’t abide by the book of rules! He is the man upon whom the responsibility falls. The company wipe their hands and say, “We are not responsible. Our employee was negligent. Here are our rules.”

And through this book of rules they are able to fix the responsibility of every accident on some poor devil like that engineer, who said the other day, after a frightful accident, when he was arrested, “Yes, but if I didn’t get the train in at a certain time I might have lost my job under the new management on the New Haven road.” That book rules exists in Europe as well. In one station in France there was an accident and the station master was held responsible. The station masters were organized in the Railwaymen’s Union. And they went to the union and asked for some action. The union said, “The best thing for you men to do is to go back on the job and obey that book of rules letter for letter. If that is the only reason why accidents happen we will have no accidents hereafter.” So they went back and when a man came up to the ticket office and asked for a ticket to such-and-such a place, the charge being so much, and would hand in more than the amount, he would be told, “Can’t give you any change. It says in the book of rules a passenger must have the exact fare.” This was the first one. Well, after a lot of fuss they chased around and got the exact change, were given their tickets and got aboard the train. Then when the train was supposedly ready to start the engineer climbed down, the fireman followed and they began to examine every bolt and piece of mechanism on the engine. The brakeman got off and began to examine everything he was supposed to examine. The passengers grew very restless. The train stood there about an hour and a half. They proceeded to leave the train. They were met at the door by an employee who said, “No, it’s against the rules for you to leave the train once you get into it, until you arrive at your destination.” And within three days the railroad system of France was so completely demoralized that they had to exonerate this particular station master, and the absurdity of the book of rules had been so demonstrated to the public that they had to make over their system of operation before the public would trust themselves to the railroad any further.

This book of rules has been tried not only for the purpose of exoneration; it has been tried for the purpose of strikes. Where men fail in the open battle they go back and with this system they win. Railroad men can sabotage for others as well as for themselves. In a case like the miners of Colorado where we read there that militiamen were sent in against the miners. We know that they are sent against the miners because the first act of the militia was to disarm the miners and leave the mine guards, the thugs, in possession of their arms. Ludlow followed! The good judge O’Brien went into Calumet, Mich., and said to the miners — and the president of the union, Mr. Moyer, sits at the table as chairman while he said it — “Boys, give up your guns. It is better for you to be shot than it is to shoot anybody.” Now, sabotage is not violence, but that does not mean that I am deprecating all forms of violence. I believe for instance in the case of Michigan, in the case of Colorado, in the case of Roosevelt, N. J., the miners should have held onto their guns, exercised their “constitutional right” to bear arms, and, militia or no militia, absolutely refused to give them up until they saw the guns of the thugs and the guns of the mine guards on the other side of the road first. And even then it might be a good precaution to hold on to them in case of danger! Well, when this militia was being sent from Denver up into the mining district one little train crew did what has never been done in America before; something that caused a thrill to go through the humblest toiler. If I could have worked for twenty years just to see one little torch of hope like that, I believe it worth while. The train was full of soldiers. The engineer, the fireman, all the train crew stepped out of the train and they said, “We are not going to run this train to carry soldiers in against our brother strikers.” So they deserted the train, but it was then operated by a Baldwin detective and a deputy sheriff. Can you say that wasn’t a case where sabotage was absolutely necessary?

Suppose that when the engineer had gone on strike he had taken a vital part of the engine on strike with him, without which it would have been impossible for anyone to run that engine. Then there might have been a different story. Railroad men have a mighty power in refusing to transport soldiers, strike-breakers and ammunition for soldiers and strike-breakers into strike districts. They did it in Italy. The soldiers went on the train. The train guards refused to run the trains. The soldiers thought they could run the train themselves. They started and the first signal they came to was “Danger”. They went along very slowly and cautiously, and the next signal was at “Danger”. And they found before they had gone very far that some of the switches had been turned and they were run off on to a siding in the woods somewhere. Laboriously they got back onto the main track. They came to a drawbridge and the bridge was turned open. They had to go across in boats and abandon the train. That meant walking the rest of the way. By the time they got into strike district the strike was over. Soldiers who have had to walk aren’t so full of vim and vigor and so anxious to shoot “dagoes” down when they get into a strike district as when they ride in a train manned by union men.

The railroad men have mighty power in refusing to run these trains and putting them in such a condition that they can’t be run by others. However, to anticipate a question that is going to be asked about the possible disregard for human life, remember that when they put all the signals at danger there is very little risk for human life, because the train usually has to stop dead still. Where they take a vital part of the engine away the train does not run at all. So human life is not in danger. They make it a practice to strike such a vital blow that the service is paralyzed thereafter.

With freight of course they do different things. In the strike of the railroad workers in France they transported the freight in such a way that a great trainload of fine fresh fruit could be run off into a siding in one of the poorest districts of France. It was left to decay. But it never reached the point of either decay or destruction. It was usually taken care of by the poor people of that district. Something that was supposed to be sent in a rush from Paris to Havre was sent to Marseilles. And so within a very short time the whole system was sos.”

Now, what is true of the railroad workers is also true of the newspaper workers. Of course one can hardly imagine any more conservative element to deal with than the railroad workers and the newspaper workers. Sometimes you will read a story in the paper that is so palpably false, a story about strikers that planted dynamite in Lawrence for instance (and it came out in a Boston paper before the dynamite was found), a story of how the Erie trains were “dynamited” by strikers in Paterson; but do you realize that the man who writes that story, the man who pays for that story, the owners and editors are not the ones that put the story into actual print? It is put in print by printers, compositors, typesetters, men who belong to the working class and are members of unions. During the Swedish general strike these workers who belonged to the unions and were operating the papers rebelled against printing lies against their fellow strikers. They sent an ultimatum to the newspaper managers: “Either you print the truth or you’ll print no papers at all.” The newspaper owners decided they would rather print no paper at all than tell the truth. Most of them would probably so decide in this country, too. The men went on strike and the paper came out a little bit of a sheet, two by four, until eventually they realized that the printers had them by the throat, that they could not print any papers without the printers. They sent for them to come back and told them, “So much of the paper will belong to the strikers and they can print what they please in it.”

But other printers have accomplished the same results by sabotage. In Copenhagen once there was a peace conference and a circus going on at the same time. The printers asked for more wages and they didn’t get them. They were very sore. Bitterness in the heart is a very good stimulus for sabotage. So they said, “All right, we will stay right at work, boys, but we will do some funny business with this paper, so they won’t want to print it tomorrow under the same circumstances.” They took the peace conference, where some high and mighty person was going to make an address on international peace and they put that man’s speech in the circus news; they reported the lion and the monkey as making speeches in the peace conference and the Honorable Mr. So-and-so doing trapeze acts in the circus. There was great consternation and indignation in the city. Advertisers, the peace conference, the circus protested. The circus would not pay their bill for advertising. It cost the paper as much, eventually, as the increased wages would have cost them, so that they came to the men figuratively on their bended knees and asked them, “Please be good and we will give you whatever you ask.” That is the power of interfering with industrial efficiency by bad service. It is not the inefficiency of a poor workman, but the deliberate withdrawal of efficiency by a competent worker.

“Used Sabotage, But Didn’t Know What You Called It”

Sabotage is for the workingman an absolute necessity. Therefore it is almost useless to argue about its effectiveness. When men do a thing instinctively continually, year after year and generation after generation, it means that that weapon has some value to them. When the Boyd speech was made in Paterson, immediately some of the socialists rushed to the newspapers to protest. They called the attention of the authorities to the fact that the speech was made. The secretary of the socialist party and the organizer of the socialist party repudiated Boyd. That precipitated the discussion into the strike committee as to whether speeches on sabotage were to be permitted. We had tried to instill into the strikers the idea that any kind of speech was to be permitted; that a socialist or a minister or a priest, a union, organizer, an A. F. of L. man, a politician, an I. W. W. man, an anarchist, anybody should have the platform. And we tried to make the strikers realize. “You have sufficient intelligence to select for yourselves. If you haven’t got that, then no censorship over your meetings is going to do you any good.” So they had a rather tolerant spirit and they were not inclined to accept this socialist denunciation of sabotage right off the reel. They had an executive session and threshed it out and this is what occurred.

One worker said, “I never heard of this thing called sabotage before Mr. Boyd spoke about it on the platform. I know once in a while when I want a half-day off and they won’t give it to me I slip the belt off the machine so it won’t run and I get my half day. I don’t know whether you call that sabotage, but that’s what I do.”

Another said, “I was in the strike of the dyers eleven years ago and we lost. We went back to work and we had these scabs that had broken our strike working side by side with us. We were pretty sore. So whenever they were supposed to be mixing green we saw to it that they put in red, or when they were supposed to be mixing blue we saw to it that they put in green. And soon they realized that scabbing was a very unprofitable business. And the next strike we had, they lined up with us. I don’t know whether you call that sabotage, but it works.”

As we went down the line, one member of the executive committee after another admitted they had used this thing but they “didn’t know that was what you called it!” And so in the end democrats, republicans, socialists, all I. W. W.’s in the committee voted that speeches on sabotage were to be permitted, because it was ridiculous not to say on the platform what they were already doing in the shop.

And so my final justification of sabotage is its constant use by the worker. The position of speakers, organizers, lecturers, writers who are presumed to be interested in the labor movement, must be one of two. If you place yourself in a position outside of the working class and you presume to dictate to them from some “superior” intellectual plane, what they are to do, they will very soon get rid of you, for you will very soon demonstrate that you are of absolutely no use to them. I believe the mission of the intelligent propagandist is this: we are to see what the workers are doing, and then try to understand why they do it; not tell them it’s right or it’s wrong, but analyze the condition and see if possibly they do not best understand their need and if, out of the condition, there may not develop a theory that will be of general utility. Industrial unionism, sabotage are theories born of such facts and experiences. But for us to place ourselves in a position of censorship is to alienate ourselves entirely from sympathy and utility with the very people we are supposed to serve.

Sabotage is objected to on the ground that it destroys the moral fiber of the individual, whatever that is! The moral fibre of the workingman! Here is a poor workingman, works twelve hours a day seven days a week for two dollars a day in the steel mills of Pittsburg. For that man to use sabotage is going to destroy his moral fiber. Well, if it does, then moral fiber is the only thing he has left. In a stage of society where men produce a completed article, for instance if a shoemaker takes a piece of raw leather, cuts it, designs it, plans the shoes, makes every part of the shoes, turns out a finished product, that represents to him what the piece of sculpturing represents to the artist, there is joy in handicraftsmanship, there is joy in labor. But can anyone believe that a shoe factory worker, one of a hundred men, each doing a small part of the complete whole, standing before a machine for instance and listening to this ticktack all day long — that such a man has any joy in his work or any pride in the ultimate product? The silk worker for instance may make beautiful things, fine shimmering silk. When it is hung up in the window of Altman’s or Macy’s or Wanamaker’s it looks beautiful. But the silk worker never gets a chance to use a single yard of it. And the producing of the beautiful thing instead of being a pleasure is instead a constant aggravation to the silk worker. They make a beautiful thing in the shop and then they come home to poverty, misery, and hardship. They wear a cotton dress while they are weaving the beautiful silk for some demi monde in New York to wear.

I remember one night we had a meeting of 5,000 kiddies. (We had them there to discuss whether or not there should be a school strike. The teachers were not telling the truth about the strike and we decided that the children were either to hear the truth or it was better for them not to go to school at all.) I said, “Children, is there any of you here who have a silk dress in your family? Anybody’s mother got a silk dress?” One little ragged urchin in front piped up, “Shure, me mudder’s got a silk dress.”

I said, “Where did she get it?” — perhaps a rather indelicate question, but a natural one.

He said, “Me fadder spoiled the cloth and had to bring it home.”

The only time they get a silk dress is when they spoil the goods so that nobody else will use it; when the dress is so ruined that nobody else would want it. Then they can have it. The silk worker takes pride in his products! To talk to these people about being proud of their work is just as silly as to talk to the street cleaner about being proud of his work, or to tell the man that scrapes out the sewer to be proud of his work. If they made an article completely or if they made it all together under a democratic association and then they had the disposition of the silk — they could wear some of it, they could make some of the beautiful salmon-colored and the delicate blues into a dress for themselves — there would be pleasure in producing silk. But until you eliminate wage slavery and the exploitation of labor it is ridiculous to talk about destroying the moral fiber of the individual by telling him to destroy “his own product.” Destroy his own product! He is destroying somebody else’s enjoyment, somebody else’s chance to use his product created in slavery. There is another argument to the effect that “If you use this thing called sabotage you are going to develop in yourself a spirit of hostility, a spirit of antagonism to everybody else in society, you are going to become sneaking, you are going to become cowardly. It is an underhanded thing to do.” But the individual who uses sabotage is not benefiting himself alone. If he were looking out for himself only he would never use sabotage. It would be much easier, much safer not to do it. When a man uses sabotage he is usually intending to benefit the whole; doing an individual thing but doing it for the benefit of himself and others together. And it requires courage. It requires individuality. It creates in that workingman some self-respect for and self-reliance upon himself as a producer. I contend that sabotage instead of being sneaking and cowardly is a courageous thing, is a good job, how many of you would risk it to employ sabotage? Consider that and then you have the right to call the man who uses it a coward — if you can.

It is my hope that the workers will not only “sabotage” the supply of products, but also the over-supply of producers. In Europe the syndicalists have carried on a propaganda that we are too cowardly to carry on in the United States as yet. It is against the law. Everything is “against the law,” once it becomes large enough for the law to take cognizance that it is in the best interests of the working class. If sabotage is to be thrown aside because it is construed as against the law, how do we know that next year free speech may not have to be thrown aside? Or free assembly or free press? That a thing is against the law, does not mean necessarily that the thing is not good. Sometimes it means just the contrary: a mighty good thing for the working class to use against the capitalists. In Europe they are carrying on this sort of limitation of product: they are saying, “Not only will we limit the product in the factory, but we are going to limit the supply of producers. We are going to limit the supply of workers on the market.” Men and women of the working class in France and Italy and even Germany today are saying, “We are not going to have ten, twelve and fourteen children for the army, the navy, the factory and the mine. We are going to have fewer children, with quality and not quantity accentuated as our ideal who can be better fed, better clothed, better equipped mentally and will become better fighters for the social revolution.” Although it is not a strictly scientific definition I like to include this as indicative of the spirit that produces sabotage. It certainly is one of the most vital forms of class warfare there are, to strike at the roots of the capitalist system by limiting their supply of slaves and creating individuals who will be good soldiers on their own behalf.

I have not given you a rigidly defined thesis on sabotage because sabotage is in the process of making. Sabotage itself is not clearly defined. Sabotage is as broad and changing as industry, as flexible as the imagination and passions of humanity. Every day workingmen and women are discovering new forms of sabotage, and the stronger their rebellious imagination is the more sabotage they are going to invent, the more sabotage they are going to develop. Sabotage is not, however, a permanent weapon. Sabotage is not going to be necessary, once a free society has been established. Sabotage is simply a war measure and it will go out of existence with the war, just as the strike, the lockout, the policeman, the machine gun, the judge with his injunction, and all the various weapons in the arsenals of capital and labor will go out of existence with the advent of a free society. “And then,” someone may ask, “may not this instinct for sabotage have developed, too far, so that one body of workers will use sabotage against another; that the railroad workers, for instance, will refuse to work for the miners unless they get exorbitant returns for labor?” The difference is this: when you sabotage an employer you are sabotaging somebody upon whom you are not interdependent, you have no relationship with him as a member of society contributing to your wants in return for your contribution. The employer is somebody who depends absolutely on the workers. Whereas, the miner is one unit in as society where somebody else supplies the bread, somebody else the clothes, somebody else the shoes, and where he gives his product in exchange for someone else’s; and it would be suicidal for him to assume a tyrannical, a monopolistic position, of demanding so much for his product that the others might cut him off from any other social relations and refuse to meet with any such bargain. In other words, the miner, the railroad worker, the baker is limited in using sabotage against his fellow workers because he is interdependent on his fellow workers, whereas he is not materially interdependent on the employer for the means of subsistence.

But the worker will not be swerved from his stern purpose by puerile objections. To him this is not an argument but a struggle for life. He knows freedom will come only when his class is willing and courageous enough to fight for it. He knows the risks, far better than we do. But his choice is between starvation in slavery and starvation in battle. Like a spent swimmer in the sea, who can sink easily and apathetically into eternal sleep, but who struggles on to grasp a stray spar, suffers but hopes in suffering — so the worker makes his choice. His wife’s worries and tears spur him forth to don his shining armor of industrial power; his child’s starry eyes mirror the light of the ideal to him and strengthens his determination to strike the shackles from the wrists of toil before that child enters the arena of industrial life; his manhood demands some rebellion against daily humiliation and intolerable exploitation. To this worker, sabotage is a shining sword. It pierces the nerve centers of capitalism, stabs at its hearts and stomachs, tears at the vitals of its economic system. It is cutting a path to freedom, to ease in production and ease in consumption.

Views: 65